From the ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting

Pediatric antibacterial use increases arthritis risk1

Horton et al performed a nested case-control study to determine if antibiotic exposure increased the development of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). According to the authors, the development of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in children has been linked to antibiotic exposure. They evaluated a comprehensive United Kingdom population-based records database (The Health Improvement Network), including diagnostic data and outpatient prescriptions. Children diagnosed with JIA prior to age 17 were identified and matched for age and sex to control subjects. There were 153 patients with a JIA diagnosis identified and 1,530 control subjects. After adjusting for confounders, any antibiotic exposure was linked with a greater probability of developing JIA, which increased in a dose-dependent manner. Similarities existed among the antibacterial medication classes evaluated. These data may support the theory that increasing antibacterial drug exposure may contribute to inflammatory disease development.

Gout hospitalizations preventable through appropriate outpatient management2

Sharma et al retrospectively evaluated cases from 2009 to 2013 for patients hospitalized with a primary discharge diagnosis of gout (56 of 79 were identified). Cases were identified as to whether or not the hospitalization was preventable. Fifty cases (89%) were identified as being preventable in that they had gout without concomitant illness requiring hospitalization. Admission diagnoses were septic arthritis (76%), inflammatory polyarthritis (14%) and cellulitis (8%). Of the 50 preventable cases, 35 had a prior history of gout. Primary care providers managed 74% of these patients, and 26% of patients were managed by rheumatologists. Of the 26 patients followed by primary care providers, 31% (n=8) were receiving urate-lowering therapies, and 19% (n=5) were on prophylactic colchicine. Eighteen of 23 (78%) patients were not at goal serum uric acid levels (< 6 mg/dL) within one year of hospitalization. Of 15 patients receiving long-term gout therapy, 33% were nonadherent. The authors concluded that 89% of gout hospitalizations are preventable, and despite ACR/EULAR gout guidelines, many patients still suffer disease flares, pain and hospitalization while increasing healthcare utilization due to inadequate disease control. By decreasing gaps in clinical care, the authors hope to improve outcomes in their health system by better following of the guidelines. This includes doing a better job of putting patients on urate-lowering therapy and colchicine at the first sign of a disease flare. Involving rheumatologists in more patient care could also help improve patient outcomes.

Better integration of hepatotoxicity monitoring needed for improved patient care3

The broadly prescribed potentially hepatotoxic agents, leflunomide (LEF) and methotrexate (MTX), are used to treat rheumatologic and other immune-mediated diseases. Currently, guidelines suggest monitoring either the AST or ALT every two to three months, even for patients on a stable, long-term medication dose. Hepatotoxicity monitoring guideline adherence was evaluated in this Kaiser Permanente (KP) study of a large, community-based population. The KP database was queried for patients who received at least two prescriptions of MTX or LEF, with at least one prescription received in the prior six months. Monitoring guideline adherence was defined as having an ALT or AST measurement and result in the 90 days prior to data collection. There were 8,276 internal medicine patients identified. Adherence to guidelines for rheumatologists ranged from 62% to 95%. Rheumatologists were surveyed, and all were aware of the guidelines and prescribed a three-month supply or less of medicine, and 94% used standing laboratory orders. In addition, 71% of rheumatologists would not refill an MTX or LEF prescription without an AST or ALT in the prior three months. The authors note significant variation in liver toxicity monitoring in this managed care group of rheumatologists. They note the need for better tools and workflows that integrate prescribing and monitoring, which could be implemented at the system level and be applicable for many different drugs, different diseases and specialties.

Prescribing antirheumatic drugs or biologics during pregnancy4

Panchel et al performed a systematic update on consensus papers of antirheumatic and biologic agents and reproduction. Medical subject heading (MESH) and free text was used to search for drug names, rheumatic disease and pregnancy. English language papers from 2006 through 2013 in Embase, Cochrane, PubMed, Lactmed and the UK Teratology Information service were systematically searched. Original pregnancy outcome data were identified in 352 papers. Drugs identified in these papers included abatacept, adalimumab, azathioprine, certolizumab, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, etanercept, hydroxychloroquine, infliximab, LEF, MTX, mycophenolate mofetil, prednisolone, sulfasalazine and anti-TNFα combinations (infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, certolizumab). The evidence from this review supports the compatibility of using azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine and steroids in pregnancy. There is increasing evidence of compatibility, mostly at conception or during the first trimester, found from pregnancies exposed to anti-TNFα agents, that does not show an appreciable increase in the number of spontaneous miscarriages and congenital malformations. The authors note that further registry data are required for biologic agents before they can safely be recommended throughout pregnancy.

Hydrocodone Combination Products

Rescheduling to control misuse & abuse

Hydrocodone combination products (HCPs) are among the most commonly prescribed opioid analgesics in the U.S., with 137 million prescriptions dispensed in 2013.5 Widespread use of hydrocodone has contributed significantly to opioid misuse and abuse. Since the Controlled Substances Act was passed in 1970, hydrocodone-only products have been Schedule II (C-II) controlled substances; whereas, HCPs have been Schedule III (C-III) controlled substances. Effective Oct. 6, 2014, a final rule by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) moved HCPs from C-III to C-II, placing more restrictions on their use.6

Key changes to the rescheduling of HCPs:

- Prescriptions for HCPs that were issued on or after Oct. 6, 2014, must comply with requirements for Schedule II prescriptions;

- Refills are not allowed on new HCP prescriptions;

- Prescriptions for HCPs may be written on a hard copy, original prescription or received by electronic transmission, where allowed. Receipt by fax will not be allowed;

- Pharmacies must use a DEA Form 222 to purchase HCPs from a distributor. Purchasing and stocking HCPs will require additional recordkeeping and security requirements;

- Prescriptions for HCPs that are issued before Oct. 6, 2014, that have authorized refills may be dispensed in accordance with DEA rules for refilling, partial filling, transferring and central filling Schedule III-V controlled substances until April 8, 2015. However, state law, insurance limitations, and some pharmacy quality and safety operations and processes may not allow for these prescriptions to be refilled. Prescribers should be prepared to provide a new hard copy or a new electronic prescription for patients after Oct. 6, 2014, rather than have patients use what would have been existing refills;

- Pharmacies may continue to dispense HCPs in commercial containers labeled as Schedule III controlled substances, rather than placing the medication in a prescription vial. However, the DEA requires all other commercial containers of HCPs to be labeled as Schedule II controlled substances (this applies to manufacturers and distributors);

- The DEA permits prescribers to issue multiple prescriptions authorizing a patient to receive a total of up to a 90-day supply of HCPs; and

- Phone-in refills for HCPs are no longer allowed except for emergency situations. In these emergency cases, a small supply of up to five days may be authorized for filling and dispensing until a new “hard copy” prescription can be provided to the pharmacy for the patient. The new prescription must be provided to the pharmacy within seven days of the phoned-in emergency prescription. The face of the prescription must state, “Authorization for Emergency Dispensing.”

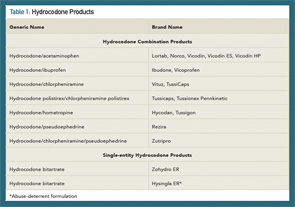

In 2012, the FDA approved a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) for highly potent opioids, such as extended-release (ER) and long-acting (LA) medications.7,8 A major goal of opioid REMS programs was to reduce harm from prescription opioid misuse and abuse while continuing to provide access to these medications for patients’ pain management. Another strategy to achieve the goal of reducing harm from opioids was the development of abuse-deterrent formulations. Abuse-deterrent formulations are designed to reduce people’s ability to extract the active opioid ingredient from the dosage form. Individuals can try to do this by chewing the formulations and/or smashing them into a powder so they snort or inject the opioid. In late November (2014), the FDA approved hydrocodone bitartrate (Hysingla ER) as an “abuse-deterrent” tablet that cannot be easily crushed or chewed.9 The product forms a thick gel when crushed, making it difficult to inject. At the time of this writing, Table 1 lists the currently available HCPs and single-entity hydrocodone products.

New federal regulations will require additional planning to prevent disruption in workflow and to avoid gaps in pain management. Research gaps exist related to opioid efficacy and management, including lack of effectiveness studies on long-term benefits and harm of opioids for use in chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP).10 Patients on chronic opioid therapy should be managed according to best practices and universal precautions, such as screening for depression and not using concomitant sedative-hypnotics or benzodiazepines.11 Strategies to provide optimal care to CNCP need to be balanced with efforts to mitigate opioid prescription abuse.

Brodalumab Drug Update

The monoclonal antibody, brodalumab, met its primary endpoints in a late-stage study in adult patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis compared with ustekinumab and placebo.12 Brodalumab targets an interleukin (IL) 17 receptor to inhibit inflammatory signaling. The AMAGINE-2 trial included more than 1,800 patients who were randomized to receive either brodalumab 140 mg, brodalumab 210 mg, ustekinumab or placebo every two weeks for 12 weeks. Patients in the brodalumab arms were then re-randomized to receive one of four different maintenance brodalumab regimens. PASI 100 was achieved in 44% of brodalumab 210 mg-treated patients, and 34% of patients in a prespecified weight-based group also achieved PASI 100, vs. 22% of ustekinumab-treated patients. PASI 75 scores were more comparable between the different groups. Brodalumab-treated patients (77–86%) achieved PASI 75, and 70% of ustekinumab-treated patients achieved PASI 75 vs. 8% of placebo-treated patients.

Michele B. Kaufman, PharmD, CGP, RPh, is a freelance medical writer based in New York City and a pharmacist at New York Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital.

Mary Choy, PharmD, CGP, RPh, is an associate professor at the Touro College of Pharmacy in New York and a clinical pharmacist at Metropolitan Hospital in New York.

References

- Horton DB, Scott IV FI, Haynes K, et al. Antibiotic exposure and the development of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A population-based case-control study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(11):Suppl. Abstract 929.

- Sharma TS, Harrington TM, Olenginski TP. Aim for better gout control: A retrospective analysis of preventable hospital admissions for gout. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(11):Suppl. Abstract 2322.

- Goldfien R, Herrinton L Monitoring methotrexate and leflunomide treatment for liver toxicity: The Kaiser Permanente experience. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(11):Suppl. Abstract 1360.

- Panchal S, Flint J, van de Venne M, et al. A systematic analysis of the safety of prescribing anti-rheumatic immunosuppressive and biologic drugs in pregnant women. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(11):Suppl. Abstract 1358.

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2014 Sep. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf.

- Drug Enforcement Administration. Schedules of Controlled Substances: Rescheduling of Hydrocodone Combination Products from Schedule III to Schedule II. 2014 Aug 22. http://www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=DEA-2014-0005-0588.

- FDA. Opioid drugs and risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS). 2014 Oct 9. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm163647.htm.

- FDA. List of long-acting and extended-release opioid products required to have an opioid REMS. 2013 Apr 22. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm251735.htm.

- FDA. FDA approves extended-release, single-entity hydrocodone product with abuse-deterrent properties. 2014 Nov 20. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm423977.htm.

- Chou R, Ballantyne JC, Fanciullo GJ, et al. Research gaps on use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain: Findings from a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society and American Academy of Pain Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Pain. 2009;10:147–159.

- Franklin GM. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: A position paper of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;83(14):1277–1284.

- Barber J. Amgen, AstraZeneca’s brodalumab meets primary endpoints of third Phase III trial in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. 2014 Nov 25. http://www.firstwordpharma.com/node/1248329?tsid=33&tsid=17#axzz3KDqIyQjQ.