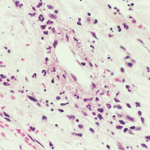

IgA vasculitis is poorly understood, but it mainly affects the skin, the joints, the gastrointestinal tract and the kidneys.

John Watney / Science Source.com

CHICAGO—Diagnosing and treating IgA vasculitis—leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving deposits of IgA1 deposits on the walls of small vessels—is rife with uncertainties, outright unknowns and treatment challenges, an expert on the disease said at the ACR’s 2016 State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium.

Alexandra Villa-Forte, MD, MPH, staff physician at Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Vasculitis Care and Research, said IgA vasculitis—which used to be known as Henoch-Schönlein purpura and mainly affects children—is poorly understood. It mainly affects the skin, the joints, the gastrointestinal tract and the kidneys, but it can arise in nearly any organ, she said.

Incidence

It appears that there could be a strong environmental component to the disease. In children, peak incidence comes in fall and winter, and the disease is often seen following respiratory infections.

The annual incidence in children is 3–26 cases per 100,000 children—quite a wide range—and is anywhere from two to 33 times more common in children than adults. About 90% of cases are believed to occur in children younger than 10, Dr. Villa-Forte said.

“The problems with defining the disease make it hard to know the incidence of the disease,” she said.

Criteria

Efforts to write criteria to describe it have been only somewhat successful, she said. For example, the 1990 ACR criteria said that someone had the disease if they exhibited two of these four: 20 years old or younger; palpable purpura; acute abdominal pain; or biopsy showing granulocytes in the walls of small arterioles or venules. But because most of those getting the disease are children, they already meet one of the criteria, and that can lead to excessive sensitivity, Dr. Villa-Forte said.

Under the EULAR criteria for children—not adapted for adults—IgA vasculitis is considered to be present with purpura and either abdominal pain, IgA finding on histopathology, arthritis or arthralgia, or renal involvement.

If someone exhibits the “classic triad” for the disease—purpura, arthralgia and abdominal pain—suspicion is raised, but those are not always present, Dr. Villa‑Forte said.

“If you don’t have a high suspicion for the disease clinically, it’s hard to make this diagnosis,” she said.

Cutaneous purpura is universal in the disease, with arthralgias in about two-thirds of the cases, but arthritis is rare. GI involvement is also seen about two-thirds of the time, and intussusception, infarction and perforation are possible.

The disease is seen in the kidney between 45% and 85% of the time, with renal insufficiency seen about 30% of the time in adults, but in children, kidney involvement is much rarer.

Adult vs. Pediatric Presentation

There are major differences between the child and the adult versions of the disease. In adults, renal issues are worse; the disease tends to be relapsing-remitting rather than self-limiting, as in children; there tend to be more complications; and the response to treatment is largely unknown because almost all of the studies have been done in pediatrics.

Also in adults, there is no seasonal pattern, while in children it tends to be seen in fall and winter; there are multiple causes in adults, while in children it tends to follow an infection. Children tend to fare better, with a complete recovery rate of about 80%, compared with 40% in adults, and chronic renal failure is seen in 2% of children, compared with about 10% of adults.

Testing

A clinical question surrounding IgA vasculitis is whether it’s helpful to do direct immunofluorescence (DIF) along with a biopsy. One study, now fairly dated and not replicated, found that DIF had a low predictive value in cases with a low clinical suspicion.1

“That’s just one thing to think [about],” Dr. Villa-Forte said. “I think at this stage of the understanding of this disease that we still need these studies in all patients.”

The ideal is to have a fitting clinical presentation, along with a tissue biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis with IgA deposits.

“If you have all this, then you can be sure about the diagnosis, but if you don’t, there’s always the possibility that it’s not the right diagnosis,” she said.

Pathophysiology

The disease is brought about by the deposits of polymers involving molecules of IgA1 that are galactose deficient, a status that appears as though it might be altered by genetics.

“It’s a high molecular polymer that is very heavy and deposits more easily,” Dr. Villa-Forte said.

A key question is what happens from the time of the deposit to when disease occurs.

“That’s what we don’t know,” said Dr. Villa‑Forte.

Factors that could play an important role include CD89, the human IgA Fc receptor, and CD71, a receptor that’s in the monocyte where the aggregate links.

Treatment

“That might be the hope for two things: diagnostic tests and treatment,” Dr. Villa‑Forte said. “We do not have good treatment or treatment that has been proved to make any difference in nephritis.”

Treating kidney issues can be especially difficult, she said.

The number of extracapillary crescents and the severity score on renal biopsy are important because they can factor into whether to treat a patient before creatinine starts to rise, but it’s controversial because it involves a biopsy for every patient.

Then there’s this problem: Many patients do well despite these findings.

“So even though we’re still trying to find and identify predictive factors, they’re not good, because the majority of people will do well, so identifying the patient who won’t do well is the challenge.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

Reference

- Sais G, Vidaller A, Jucglá A, et al. Prognostic factors in leukocytoclastic vasculitis: A clinicopathologic study of 160 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998 Mar;134(3):309–315.