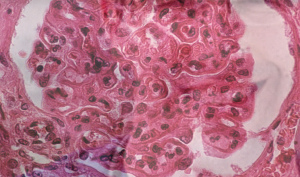

The pattern of lupus glomerular involvement in this patient with lupus nephritis is similar to that in membranous nephropathy, forming wire-loops lesions.

Biophoto Associates/SCIENCESOURCE.COM

The following summary regarding use of tacrolimus (TAC) in lupus nephritis highlights a number of debatable points. Although the role of TAC in lupus nephritis remains unproved for North American populations, it might be an excellent option in some clinical situations. These situations include lupus flare during pregnancy and also for lupus nephritis when the other anchor drugs, such as mycophenolate (MMF) and cyclophosphamide (CYC), have failed. Adding TAC may be especially applicable when rituximab cannot be used as a preferred adjunct therapy.

A summary of data supporting this conclusion follows, in the context of mechanisms of action of TAC in nephritis and risks.

Background: History, Mechanisms & Risks

Calcineurin inhibitors carry historical importance in nephrology. Anti-metabolites, such as the pyrimidine analogue azathioprine, and corticosteroids made renal transplant feasible, but it is the calcineurin inhibitors that advanced the transplant era. Calcineurin inhibitors proved to work well in idiopathic membranous nephritis with nephrotic range proteinuria. Conventionally, it is also thought to be of most value in lupus nephritis when the biopsy reflects a large membranous component.

The ways in which calcineurin inhibitors lead to faster resolution of proteinuria in lupus nephritis include several pleiotropic, non-immunosuppressive, off-target effects. Studies have demonstrated that calcineurin inhibitors cause vasoconstriction of the afferent and efferent glomerular arterioles, that results in decrease in single nephron filtration pressure and, therefore, degree of proteinuria. Additionally, a direct effect upon podocytes by stabilizing podocyte actin cytoskeleton and inhibiting podocyte apoptosis has been postulated.1 Regardless of mechanism, less proteinuria is good—it just may not be equally good for all mechanisms leading to reduced proteinuria.

The most common side effects of calcineurin inhibitors include nephrotoxicity, hypertension, neurotoxicity and metabolic abnormalities. Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity is manifest either as acute azotemia, which is largely reversible after reducing the dose, or as chronic progressive renal disease, which is usually irreversible. Up to 17% of patients within three years of therapy may have a significant loss of renal function due to drug toxicity, most of which can never be regained.2 TAC can, therefore, be a bridge to somewhere in rheumatology, but not a destination.

Recent Data

New data have reemphasized the importance of proteinuria as a cardinal prognostic feature in lupus nephritis.3 Proteinuria rivals the prognostic value of rising creatinine in conferring risk of eventual end stage of renal disease in lupus nephritis. This emphasis on proteinuria might seem to favor TAC as an adjunct or salvage treatment for lupus nephritis on the grounds that TAC can decrease the degree of proteinuria faster than MMR or CYC. However, most recently—and spectacularly—efforts to cut corticosteroid doses in induction treatment for lupus nephritis using rituximab have had good success.