Weakness implies a loss of function and a decline in strength, and it is challenging to confirm the absence, rather than the presence, of a symptom.

VasilkovS/shutterstock.com

As clinicians, we are familiar with pain, stiffness and soreness—subjective nouns that define our métier. These helpful words serve as signposts that direct us along the path to the proper diagnosis.

Consider the young man with a stiff, sore back (a case of ankylosing spondylitis?) or the postpartum woman experiencing newly painful, stiff and sore fingers (the onset of rheumatoid arthritis)? How about your patient, the weekend warrior, old enough to have been alive when Woodstock rocked, who now describes feeling stiff and sore around their shoulders and hips (polymyalgia rheumatica, perhaps)? Rheumatologists are accustomed to parsing the meaning of these terms. We are the experts in triaging aches and pains. This is the essence of rheumatology.

But interpreting another nebulous term, weakness, is another story. This noun is among the most vexing descriptors heard when taking a patient’s history, perhaps only matched by the imprecise epithets, feeling dizzy and feeling fatigued. Weakness implies a loss of function, a decline in strength, and it is always challenging to confirm the absence, rather than the presence, of a symptom. Skeletal muscle, unlike its neighboring tissues, the joints, tendons, ligaments and bursae, can silently endure an intense immune attack without raising a whimper. In contrast to all the other –itises, inflammatory myositis is generally a painless event that quietly transforms into a debilitating condition.

Because a steroid-induced myopathy is painless, patients are rarely aware of its stealthy development until the weakness begins to disrupt their lifestyle.

Hiding in Plain Sight

Years ago, some colleagues and I examined a handful of patients who presented with varying complaints of malaise, fatigue and a sense of feeling unwell that led their treating physicians astray. Several patients were noted to have elevated serum liver enzymes that, in combination with their descriptions of malaise and fatigue, led to a liver biopsy in one patient (with normal results) and consideration of this procedure in two others, creating even more diagnostic confusion. It was only when a couple of our astute fellows considered another potential source for these enzyme elevations, namely muscle, and measured the patients’ serum creatine kinase levels that the diagnosis of, what we later termed, occult myositis became evident.1

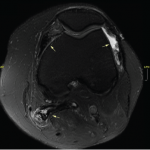

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM), such as polymyositis and dermatomyositis, can arrive with little fanfare. Occasionally, a telltale reddish scaly skin eruption may be present or a wholly unwelcome coincidental paraneoplastic event may occur, but generally, these muscle disorders may simmer along quietly, at least for a while, evading detection. After the diagnosis is made and treatment initiated, other challenges may present, such as determining whether any persistent weakness is a manifestation of ongoing muscle inflammation requiring more aggressive immunosuppression or is an expected consequence of prior muscle damage.