I came to learn that reading poetry and reflecting about humanities made me a better person and better doctor. When I introduced medical humanities to faculty and residents on bedside rounds, they, too, became measurably better physicians and probably provided demonstrably better care. Let me explain.

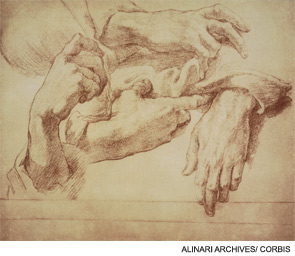

How many of you carefully look at the JAMA covers and peruse the commentaries? I do. I enjoy looking at the art and reading the commentary. Sometimes I see something familiar, sometimes my skills of examination and analysis are challenged, and usually I learn something. Did anyone notice the drawing of hands on the August 25, 2010 issue of JAMA (see Figure 1)?2 As a rheumatologist, I can’t see something like that without trying to make a diagnosis. (I have one for this—what’s yours?) And did any of you happen to see the pieces about humanities and medicine in recent issues of Academic Medicine?3-5 There is more to rheumatology than rheumatology, more to medicine than medicine, and more to life than medicine.

“Inspire me with love for my art and for Thy creatures … In the sufferer let me see within only the human being … for delicate and indefinite are the bounds of the great art of caring for the lives and health of thy creatures.”

—From The Physicians’ Daily Prayer of Maimonides1

Embark on a Humanities Journey

My interest in humanities and their relationship to medicine was rekindled on one free afternoon some years ago during a meeting in Washington, D.C. I decided to visit the National Gallery of Art at the Smithsonian. I was with my daughter, Rachel, who is an artist, and my friend from our days as fellows together, Jack Caldwell (sadly, now deceased). I had taken Art 101 and 102 as an undergraduate and had some curiosity about art, and I wanted to accommodate Rachel’s wishes to tour the museum. We came upon Corot’s “Gipsy Girl with Mandolin” (see Figure 2). I was intrigued by the subject’s deformed hand. We decided to investigate possible explanations. We offered our thoughts in an essay in JAMA, which was published along with the painting on its cover.6 We suggested that this unique artistic depiction may have reflected, in some manner, the debilitating polyarticular gout that Corot was experiencing at that time in his life.

This was the beginning of a transformation of my thinking about medicine and humanities. Art, literature, and history became an enjoyable interest. Several years ago, an opportunity arose to bring this to clinical medicine in my department. Our accrediting body, the Residency Review Committee for Internal Medicine of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, invited proposals for innovations in medical education. I was thrilled when Saint Barnabas Medical Center (where I was then medicine program director and department chair) was selected to among the 21 participating programs.