Back pain is a frequent complaint in rheumatology practices. Many patients, and older patients in particular, who present with back pain have the clinical syndrome of lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS). This article discusses several of the most daunting challenges of diagnosis and treatment of LSS, and suggests possible approaches.

Diagnostic Challenges

- The characteristic history and physical examination findings of spinal stenosis are nonspecific and insensitive. The characteristic history elicited from patients with symptomatic LSS features neurogenic claudication, a syndrome characterized by two key components. The first is radiation of the pain beyond the lumbar region. The pain of spinal stenosis typically originates in the back and radiates into the buttocks and sometimes into the thighs, lower legs, and feet. Unlike sciatica due to a herniated disk, which typically radiates in a discrete dermatomal pattern into the calves and feet, the pain of spinal stenosis often radiates more diffusely into the buttocks and upper thighs and no further. The second notable feature of neurogenic claudication is a postural component. Patients feel less pain when they are flexed forward at the spine, as in sitting, and more pain when they are extended, as in standing and walking. As Table 1 shows, the pain location and the provocation with extension and relief with flexion are diagnostically useful, but neither is perfectly sensitive nor specific.

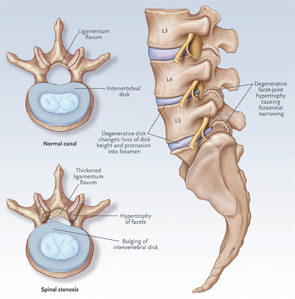

- Imaging tests are super-sensitive and nonspecific. The key imaging features of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis are shown in Figure 1. These include facet joint hypertrophy and ligamentum flavum hypertrophy and disc protrusion. The combination of these findings can result in central or neuroforaminal stenosis. The problem is that the imaging features of lumbar spinal stenosis are very common in asymptomatic individuals. Stenosis is observed on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in more than 20% of asymptomatic patients older than age 60.The diagnostic utility of an MRI positive for LSS varies according to the prior probability, which refers to the clinician’s estimate of the probability of disease before the test was performed. When the prior probability is low, say just 1%, a positive test will often turn out to be a false positive, even if the test has high sensitivity and specificity. Table 2 provides examples of prior probabilities and corresponding posttest probabilities (or positive predictive values) for a test with sensitivity and specificity of 90%. In this two-by-two table analysis, the prevalence of LSS represents the pretest probability. This table makes the point that same test has very different positive predictive values in situations of low prior probability versus higher prior probability. In the situation on the left side of the table, the prior probability, as represented by the prevalence of disease, is 1% and the posttest probability, or positive predictive value, is 8%. On the shaded right half of the table, with a prior probability of 30%, the posttest probability or positive predictive value is 79%. Thus, in the first scenario, the vast majority of positive tests are false positives. In the second scenario, four of five positive tests are true positives.

- The diagnosis of spinal stenosis frequently coexists with other common problems. These problems include osteoarthritis of the hips, trochanteric bursitis, facet syndrome, vertebral fracture, nonspecific low back pain, and vascular claudication. Clinicians must distinguish among this array of possible diagnoses to identify the primary source of pain for any particular patient. These other disorders are not necessarily difficult to identify (trochanteric bursitis and hip osteoarthritis, for example, are relatively easy diagnoses to establish); the challenge is determining which of several coexisting problems is responsible for most of the patient’s symptoms.

Potential Solutions to These Diagnostic Challenges

It is important for clinicians to listen and examine carefully, and to form an impression based on the history of physical examination findings, the patient’s age, and other such clues. If the clinician senses that spinal stenosis is reasonably likely on the basis of several history and physical examination findings, imaging tests can be useful in confirming the diagnosis. On the other hand, when the clinical picture is not compelling, imaging tests are much less valuable because positive tests are frequently misleading. If imaging tests are performed under similar circumstances, a positive imaging test (or a single positive element of the history or physical examination, for that matter) can often be disregarded.