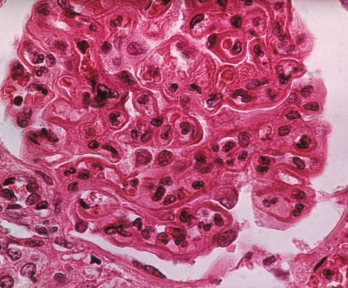

The pattern of lupus glomerular involvement in lupus nephropathy is similar to that in membranous nephropathy, forming wire-loops lesions.

Biophoto Associates / Science Source

Researchers who devote their time to studying lupus are accustomed to considering environmental stimuli such as sunshine and cigarettes. But according to Gregg J. Silverman, MD, a professor in the Department of Medicine and in the Department of Pathology at the New York University (NYU) School of Medicine and co-director of the Musculoskeletal Center of Excellence, we should be taking a closer look at the internal environment: the gut microbiome.

Dr. Silverman and colleagues set out to do a thorough search for a transmissible agent in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Their work, “Lupus Nephritis Is Linked to Disease-Activity Associated Expansions and Immunity to a Gut Commensal,” appears in the Feb. 19, 2019, online edition of the Annals of Rheumatic Diseases.1

Consider the Internal Environment

“Lupus is one of the most fascinating and challenging diseases you can imagine,” says Dr. Silverman, a practicing rheumatologist who is also a molecular immunologist. “On one level, it is an autoimmune condition where the body attacks itself—but it does so in specific patterns. The hallmark of lupus is that these patients make anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA). When there are anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies present, it often signals the development of the most serious complications of lupus. These patients are experiencing an immunological reaction to the building blocks of life.”

Dr. Silverman says research findings related to identical twins are puzzling. If one twin develops lupus, the other twin develops the disease only 25–30% of the time. “Roughly 20 years ago I had a patient who, after about two years of treatment for her lupus, told me that she had a twin. Both siblings donated blood and thus began my initial research on twins and the immune system. Whenever I see a lupus patient I now ask, ‘Perhaps it’s not always fated to happen. What’s going on in this person’s internal environment that might contribute?’”

Dr. Silverman began his translational science work at NYU in 2011. “The hunt for a transmissible agent in lupus became feasible due to the explosion of technology related to the human genome initiative,” he says. “Not only did it become less expensive to determine DNA sequences, but the software became available to sift through all of the microbiome DNA data.”

A Big Population That Bears Investigation

Dr. Silverman, notes, “The discovery that every one of us has three to 10 times more microbial cells than human cells in our body lit the fuse for me, as well as for other investigators. The gut microbiome is a vast, undiscovered world that holds promise for treating numerous diseases. For our purposes, we matched blood and fecal samples from 61 female patients with SLE, using 17 female healthy controls. We undertook fecal 16S rRNA analyses that examined genes from each microbe present in the bowel, and we performed sera profiling for antibacterial and autoantibody responses.”

Dr. Silverman says they learned that lupus patients have reduced gut microbiome diversity than healthy controls and varying levels of dysbiosis. “However, few efforts have been made to characterize the microbiome of those with active lupus,” he says.