The diagnosis of rheumatic diseases requires the exclusion of other systemic disorders. Infection, hematologic conditions, malignancies and some drugs may all lead to syndromes that closely mimic rheumatic diseases, which may lead to diagnostic delays.

Idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD) is a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative diseases (LPDs) characterized by systemic inflammatory manifestations.1,2 As with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), patients may present with autoimmune thrombocytopenia, serositis and lupus nephritis. iMCD associated with thrombocytopenia, anasarca, myelofibrosis, renal dysfunction and organomegaly (iMCD-TAFRO) represents a subset of iMCD.

Distinguishing iMCD-TAFRO from SLE is critical to determine the appropriate treatment. Here we report on a patient with iMCD-TAFRO who presented with symptoms consistent with undifferentiated connective tissue disease (UCTD).

Case Report

A 41-year-old Japanese woman presented with Raynaud’s phenomenon. Laboratory testing revealed that she had anti-nuclear antibodies (ANAs) and anti-U1 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) antibodies. A farmer, she had no other symptoms associated with SLE, scleroderma or idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Her Raynaud’s phenomenon was treated with vasodilators, and she was given a tentative diagnosis of UCTD.

Seven years later, she developed acute abdominal pain. Thickening of the gallbladder wall and gallstones were detected by ultrasound, leading to a diagnosis of acute cholecystitis. Her symptoms did not improve with fasting or antibiotic therapy, and she subsequently gained 10 kg weight in a month, and developed fever, dyspnea and abdominal distention. She was then admitted to our unit.

Laboratory results revealed anemia (hemoglobin 6.8 g/dL; normal range [NR] 11.3–15.2); thrombocytopenia (platelets 3.9×104/µL; NR 13.0×104–36.9×104); low albumin (2.6 g/dL; NR 3.8–5.2); renal dysfunction, requiring renal replacement therapy; and systemic inflammation (C-reactive protein [CRP] 55.6 mg/L; NR <3.0). We found slightly elevated levels of soluble interleukin (IL) 2 receptor (659 U/mL; NR 145–519), IL-6 (25 pg/mL; NR <4.0) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (118 pg/L, NR <38.3).

Her complement levels were normal, and tests for autoantibodies, including double-stranded-DNA (dsDNA) antibodies and anti-Ro/La antibodies, were negative. Serologies for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, human immunodeficiency virus and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) were negative.

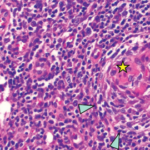

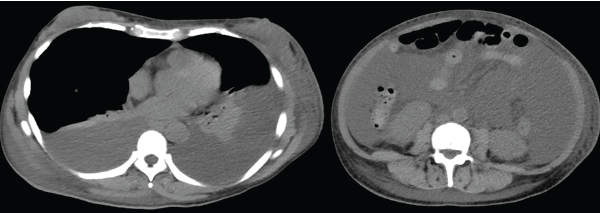

A urinalysis showed hematuria and proteinuria (urinary protein to creatinine ratio 4.69 g/g·Cr) with active urine sediment, such as granular and waxy casts. Computed tomography revealed bilateral pleural effusions, massive ascites, splenomegaly and generalized lymphadenopathy (see Figure 1, below).

Figure 1: Computed tomography demonstrates bilateral pleural effusion and massive ascites.

The patient was initially diagnosed with SLE, based on her serositis, nephritis and pancytopenia in the presence of ANA and anti-U1 RNP antibodies. We treated her with pulse methylprednisolone (1,000 mg/day for three days), followed by prednisolone (1.0 mg/kg/day), mycophenolate mofetil (2,000 mg/day) and tacrolimus (3 mg/day), with transient hemodialysis. However, her condition gradually progressed.

We performed a bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. Although the bone marrow aspiration was dry, the bone marrow biopsy led to the discovery of mild myelofibrosis with an increased number of slightly atypical, multi-nucleated megakaryocytes, consistent with a diagnosis of iMCD-TAFRO.

Despite treatment with intravenous tocilizumab (400 mg) and administration of a thrombopoietin receptor agonist, her symptoms did not improve. However, after administration of cyclosporine A (CsA, 3 mg/kg/day) with a target trough serum CsA level of 150–250 ng/mL, the patient finally achieved full recovery.