Editor’s note: EULAR 2020, the annual European Congress of Rheumatology, which was originally scheduled to be held in Frankfurt, Germany, starting June 3, was moved to a virtual format due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Editor’s note: EULAR 2020, the annual European Congress of Rheumatology, which was originally scheduled to be held in Frankfurt, Germany, starting June 3, was moved to a virtual format due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

EULAR 2020 e-CONGRESS—In the past several decades, the field of rheumatology has advanced in no small part due to an improved understanding of how the immune system works. The beautiful symphony created by each instrument of the adaptive and innate immune systems is quite a thing to behold, and researchers and clinicians are adding to this harmony by using components of the immune system as therapeutics.

At the 2020 European e-Congress of Rheumatology, June 3–6, the session titled, Dendritic Cells as Therapeutics focused on this very topic, both from a conceptual perspective, as well as with a practical focus on treatments currently approved or being tested.

Clinical Use

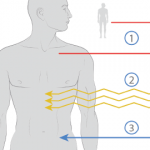

Catharien Hilkens, PhD, reader in immunotherapy, The Medical School at Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, U.K., began the lecture series by discussing how dendritic cells in their natural state serve as professional antigen-presenting cells and are equipped to initiate adaptive immune responses in the body. Given this ability, dendritic cells have been used in the treatment of cancer, autoimmunity and for patients who have undergone organ transplants. Example: In dendritic cell-based cancer immunotherapy, dendritic cells can be collected from patients, modulated outside the body and reimplanted to prime the immune system to eliminate the tumor. Dendritic cells have also been used in vaccines to present tumor-associated antigens to the patient’s immune system and prime the immune system to recognize and act against the tumor while the patient receives other cancer therapies, such as chemotherapy and monoclonal antibodies.1

With respect to organ transplantation, cell-based therapies with dendritic cells offer the potential to provide donor-specific tolerance after transplant. This is an improvement over typical immunosuppression regimens, which lack specificity and leave transplant recipients at risk of infection, cancer, medication-related toxicity and chronic rejection.2 A significant strength of dendritic cell-based therapy in transplant patients is the opportunity to create allograft-specific tolerance and promote long-term allograft survival.

Dr. Hilkens noted that, in autoimmunity, dendritic cells promote activation and differentiation of autoreactive effector T cells. If this unwanted activation could be reversed and if immune regulation could be restored, then self-tolerance should return. Human tolerogenic dendritic cells have been studied to treat inflammatory arthritis and other conditions because they produce high levels of interleukin (IL) 10 and, in mixed cultures, dominate mature, pro-inflammatory dendritic cells and down-regulate T cell activation.3