A 67–year-old white woman with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon presented following a week of progressively worsening shortness of breath, dry cough and generalized malaise. An avid tennis player, she first noticed dyspnea while playing, but a few days later grew short of breath even at rest. She went to an urgent care center, where a computed tomography (CT) scan of her chest reportedly showed an atypical pneumonia. She tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 and was discharged on oral doxycycline therapy for suspected bacterial pneumonia.

However, her shortness of breath continued to progress to the point that she was unable to speak in complete sentences. This prompted a visit to the emergency department, where she was found to be in respiratory distress. She was tachypneic with a respiratory rate of 38 per minute and hypoxemic with oxygen saturation of 70% on room air, requiring 4L per minute of supplemental oxygen to improve her saturation to 92%.

A laboratory evaluation was significant for neutrophil-predominant leukocytosis 18.1×103/uL (reference range [RR]: 4.5–11.0×103/uL), normocytic anemia with hemoglobin 8.9 g/dL (RR: 11.5–15.5 g/dL) and platelet count 492×103/uL (RR:130–400×103/uL). No evidence was found of hemolytic anemia, iron, B12 or folate deficiency. Her ferritin level was 576 ng/mL (RR: 15–150 ng/mL), her C-reactive protein (CRP) was 341.3 mg/L (RR: <6 mg/L), and her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 113 mm/hour (RR: <20 mm/hour). Her prothrombin time and international normalized ratio and partial thromboplastin time were normal. Her D-dimer was 6,069 ng/mL (RR: ≤499 ng/mL) and fibrinogen was 576 mg/dL (RR: 170–400 mg/dL). Her creatinine kinase was 44 U/L (RR: 30–300 units/L) and aldolase was 9.9 U/L (RR: 0.1–8.0 units/L). Her lactic acid was 3.8 mmol/L (RR: 0.7–2.0 mmol/L). Troponin I was undetectable, and an electrocardiogram was normal. Her urinalysis was normal.

The nasopharyngeal viral respiratory polymerase chain reaction test, Legionella urine antigen test and sputum and blood cultures were negative.

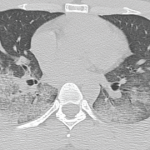

A chest CT now showed diffuse, patchy bilateral groundglass opacities and interlobular septal thickening, with small areas of dense bilateral pulmonary consolidations, trace bilateral pleural effusions, a mildly dilated esophagus and mediastinal lymphadenopathy (see Figure 1A, opposite).

Due to increasing oxygen requirements and concern for further decompensation, she was transferred to the medical intensive care unit. Here, she was started on empiric treatment for community-acquired pneumonia with ceftriaxone and azithromycin. A repeat SARS-CoV-2 test was negative. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was normal.

Three days later, she had failed to improve on antibiotic therapy and had worsening hypoxemia, requiring a non-rebreather mask. Suspicion for COVID-19 remained high, but she tested negative for a third time.

Given her history of Raynaud’s phenomenon and unremarkable infectious work-up, an autoimmune etiology was considered. She was subsequently started on 1 mg/kg of intravenous methylprednisolonone on hospital day 4, after which a consult with a rheumatologist was obtained.

She denied any history of rash, mucosal ulcers, photosensitivity, alopecia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, dysphagia, muscle pain or weakness, recurrent ear infections, sinusitis, recurrent pneumonia, epistaxis, joint pain, swelling, morning stiffness or renal disease. Prior to symptom onset, she had been completely asymptomatic. With the exception of playing tennis three or four times a week, she had limited her outside activities due to the pandemic and denied any known sick contacts.

She had previously been evaluated by a rheumatologist in the 1990s for Raynaud’s phenomenon, and she lacked anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) and rheumatoid factor (RF). She also lacked antibodies against double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), extractable nuclear antigens (ENA) and cyclic citrullinated peptides (CCP). For 20 years, she had never experienced any complications of Raynaud’s or symptoms to suggest a systemic autoimmune disease, and she had never required therapy.

Initially, given the abrupt onset of dyspnea, lack of symptoms other than uncomplicated Raynaud’s, absence of physical exam findings to suggest an autoimmune disease, previously negative serologies and normal TTE, the suspicion for an autoimmune process was low. However, her hypoxemia improved with steroids, which prompted a rheumatologic work-up.

During this time, she was also evaluated by a pulmonologist, who expressed concern for cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. A bronchoscopy was discussed, but not pursued because her oxygen requirements had decreased to 2L per minute by hospital day 6.

Given her marked improvement, she was discharged on 60 mg of prednisone and supplemental oxygen by hospital day 8. She was seen in our rheumatology clinic a few days later for follow-up labs, which revealed a markedly positive C-ANCA of 1:256 and anti-PR3 of >8 U (RR: <0.4 U). Her serologic evaluation was remarkable for a positive RF at 36 U/mL (RR: <15 U/mL), negative anti-MPO, ANA, anti-ENA, anti-dsDNA, anti-SCL-70, anti-centromere, anti-CCP, myositis panel, anti-RNA polymerase III, anti-beta 2 glycoprotein IgM and IgG, anti-cardiolipin IgM and IgG.

Based on serologies and pulmonary manifestations, she was diagnosed with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). She continued 60 mg of prednisone daily and was started on 375 mg/m2 of rituximab weekly for four weeks. She was gradually tapered to 20 mg prednisone daily by six weeks following her discharge. At that time her CRP was 2.1 mg/L and her ESR was 29 mm/hr. She was C-ANCA positive at 1:512 with anti-PR3 of 1.6. Her fatigue, cough and shortness of breath had completely resolved, and she no longer required supplemental oxygen.

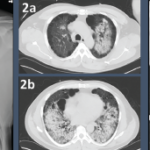

She was scheduled for a repeat CT two months post discharge, which showed dramatic improvement in the extensive bilateral infiltrates, moderate interstitial lung disease remaining more prominent in the lower lung fields, subpleural changes of obstructive pulmonary disease and mild air trapping in the lower lobes (see Figure 1B, opposite).