After 30 years of private practice in Hixson, Tenn., rheumatologist Joseph E. Huffstutter, MD, isn’t worried about squeezing in a new referral from a primary care colleague across the river in Chattanooga. Dr. Huffstutter and his four partners accommodate nonurgent referrals in about six weeks; patients with immediate needs are seen in a day or two.

But Dr. Huffstutter knows his practice is more the exception than the rule in Tennessee. Patients on the other side of the state, some 300 miles to the west in Memphis, are in far more desperate straits. “The wait time for a new patient in Memphis is six months,” says the past president of the Tennessee State Rheumatology Society. “We have more rheumatologists in Chattanooga, and Memphis is four times as big as we are.”

About 100 miles northeast in Knoxville, a city with nearly 200,000 residents and a major university, “there is a real dearth of rheumatologists,” Dr. Huffstutter says. And subspecialists are even scarcer as you travel farther north toward western Virginia. “There are several medium-size cities that just don’t have any coverage,” he says. “It’s six months or longer to get any rheumatology care.”

Patient access in rural and underserved U.S. communities is a serious issue—and not unique to rheumatology. Experts point to a multitude of reasons: an aging workforce, uncertain business climate and government regulation—to name a few.

“Access is a true, regional issue,” says Daniel Battafarano, DO, a retired U.S. Army colonel who is chief of the Rheumatology Division at San Antonio (Texas) Military Medical Center and a member of the ACR’s Committee on Rheumatology Training and Workforce Issues. “In the northeast United States, you might be a stone’s throw away from accessing a rheumatologist, but this is in dramatic contrast to Western states like Idaho or Nevada, which are underserved.”

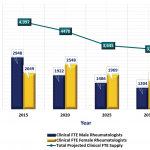

And access to subspecialists in underserved areas isn’t getting better anytime soon (see Figure 1).

“There is no doubt in my mind patient access is becoming more difficult,” Dr. Battafarano says. “It’s simple arithmetic. More than half of our rheumatologists are over age 50 and could retire in the next 10–15 years. At the same time, the population in America is expanding while we are implementing the Affordable Care Act, which generates its own access challenges.”

Source: The American College of Rheumatology, 2005 Workforce and Demographic Study

International State of Affairs

Up until the year 2000, a patient in the United Kingdom referred to a rheumatologist could wait six, nine, even 18 months for an initial visit, according to Simon Bowman, BSc, MBBS, PhD, FRCP, consultant and honorary professor of rheumatology at University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust. In 2000, however, the maximum waiting time target for outpatient appointments was set at 12 weeks.1