Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a relatively common rheumatologic disease with potentially devastating complications. It was first described in the early 1890s; however, more than a hundred years later, this large- and medium-sized vessel vasculitis continues to pose multiple challenges for rheumatologists and patients in terms of diagnosis and therapy, as well as the management and prevention of treatment complications.

GCA is the most common form of primary vasculitis among adults in Western countries, with a prevalence ranging from 24 to 280 cases per 100,000 individuals older than 50. The incidence of GCA increases progressively with age and peaks during the seventh decade of life. The disease has a particular predilection for elderly populations of northern European ancestry and is approximately twice as common in women than in men.1

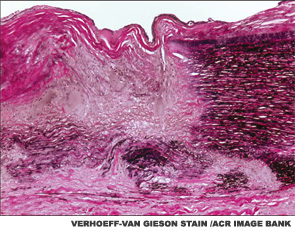

The main histopathologic feature of GCA comprises a chronic granulomatous inflammatory process that involves the aorta and its main branches, with a tendency to affect the extracranial carotid arteries and the ophthalmic circulation (see Figure 1). Its clinical manifestations consist of constitutional symptoms (e.g., asthenia, fever), headaches, jaw claudication, shoulder and hip girdle pain and stiffness (i.e., polymyalgia rheumatica) and elevated acute-phase reactants.2

The most feared consequence of GCA pertains to vision loss, occurring in 15–20% of cases. Blindness, which tends to occur before the disease is even suspected, usually occurs as the result of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) due to the occlusion of the long posterior ciliary arteries that perfuse the head of the optic nerve.

Other possible complications include scalp and tongue necrosis, aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, limb claudication from large-artery stenosis (particularly the subclavian and axillary arteries), stroke, mesenteric ischemia, myocardial infarction and venous thromboembolism.2

Classification Criteria

In 1990, the ACR classification criteria were established for the purpose of differentiating GCA from other vasculitides.3 The five components of the ACR classification criteria for GCA are shown in Table 1 (p. 22). Fulfillment of at least three of the five ACR criteria is associated with a 90% sensitivity and a 90% specificity for GCA when evaluating patients known to have one form of systemic vasculitis or another. The ACR classification criteria were not designed for use as diagnostic criteria, but rather for the purpose of ensuring greater uniformity of patient populations in studies of vasculitis.

Rendering the diagnosis of GCA is often considerably more challenging than referring to the features of the ACR classification criteria, however. The evaluation of cranial symptoms—common complaints in clinic populations—requires substantial experience and judgment.