Thromboembolic events are major contributors to the morbidity and mortality of patients with giant cell arteritis (GCA), but little is known about how GCA may increase the risk of ischemic strokes. GCA-related stroke is described as an ischemic cerebral infarct occurring within three to four weeks of GCA diagnosis and treatment. It occurs in 3–7% of patients diagnosed with GCA and has a predilection for affecting the posterior circulation.

Many patients who experience stroke after GCA diagnosis may have risk factors for atherosclerotic disease. This makes it challenging to determine how GCA may have contributed to the patient’s stroke. The standard treatment for GCA-related stroke is high-dose glucocorticoids (i.e., 500–1,000 mg/day for three days). However, even when treatment is promptly administered, morbidity and mortality rates may be high.

The Case

A 72-year-old man presented to the emergency department for progressively worsening headaches, dizziness and jaw claudication. His erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 97 mm/hr at that time, and he was diagnosed with GCA via temporal artery biopsy. He was treated with 60 mg of prednisone daily, which resolved his symptoms.

Three weeks later—while still taking prednisone at the 60 mg dose—he began feeling unwell, and his wife noted some changes in his speech. The patient awoke in the middle of the night to go to the bathroom and fell on his way back to bed due to left-sided weakness. He waited until morning—approximately six hours—before going into the emergency department.

In addition to the GCA diagnosis, he had a past medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

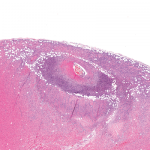

Initial brain MRI shows small areas of acute infarct in the right pons (A) and bilateral

cerebellum (B). Repeat brain MRI after sudden deterioration shows acute infarcts in the left pons with extension of infarcts in the right pons (C) and the left cerebellum (D). (Click to enlarge.)

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were within normal limits. He had severe upper and lower extremity weakness on his left side, along with left-sided facial droop and dysarthria. Laboratory testing revealed hyperglycemia of 396 mg/dL. His ESR was normal at 7 mm/hr. Throughout his emergency department stay, electrocardiograms and telemetry revealed no evidence of atrial fibrillation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an acute infarct in the right pons and bilateral inferior cerebellum (see Figures 1A and 1B). Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) revealed a diminutive appearance of the vertebral arteries and the basilar artery, as well as severe bilateral siphon stenosis of the intracranial internal carotid arteries.