We can all agree that technology for technology’s sake is problematic, but technology that solves problems is worth considering. Credit: Adobe Stock | stockdevil

Over our 25 years as rheumatologists, care has advanced greatly. We each completed our rheumatology training in the late 1990s when both infliximab and etanercept first arrived on the U.S. market, ushering in the era of biologics in rheumatology. Since this time, our greater understanding of the immunologic basis of many rheumatic diseases has translated into a growing list of targeted therapies. It’s truly a fun time to be a rheumatologist and a time when we can offer many patients effective therapies. However, the current environment of rheumatologic care has crushing access issues.

Although the number of people in the rheumatology workforce slightly increased through 2020, many younger rheumatologists are not working full time, and projected retirement numbers will result in a reduced workforce in the near future.1 The ACR projected a large and progressive shortage of rheumatologists by 2030, mostly due to rheumatology person-power shortages plus an increased demand for rheumatologic care.2 This situation has been exacerbated by early retirements attributable to burnout, a process that accelerated during and after the pandemic. Concurrent with an increasingly limited supply of rheumatologists, shifting demographics, the prevalence of anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) positivity and gradual increases in autoimmune diagnoses have increased the demands placed on the U.S. rheumatology workforce.3-5

We have not seen hard data, but colleagues from around the country describe wait times of six months or greater for a new patient, and 12 month wait times are not unusual at rural rheumatology practices;6 this situation is not sustainable.

There is a direct human cost to prolonged wait times in the rheumatic diseases—one that threatens our patients with a cascade of events leading to greater disability if traditional models of care fail to evolve to address the combined impacts of a smaller workforce and the greater demands it faces. Specifically, under the current paradigm, the supply-demand mismatch can be expected to increase wait times for initial consultation, resulting in longer time to diagnosis, and allowing greater progression of disease disability and accrual of permanent damage to joints and other organs.

Tackling the Shortage

The ACR has proposed ways to address this workforce shortage, including enhancing the number of trainees and increasing recruitment and training of advanced practice providers (APPs), such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Efforts to effectively address the epidemic of burnout may alleviate a cause of suffering among our colleagues, reducing early retirement from clinical practice. Yet these important steps to impact the supply side of the supply-demand mismatch in U.S. rheumatology are unlikely to add enough rheumatologists and interprofessional rheumatology providers quickly enough to solve the growing access problems. Are there other models of care that should be considered to improve the demand side of the equation?

A promising area to explore is how digital health technologies can improve care efficiency. The majority of rheumatologists have their schedules filled with follow-up visits. Finding data to prove this point is difficult, but our colleagues agree that approximately one-third of return visits may be discretionary for patients who have stable symptoms. While ensuring monitoring laboratories occur, answering patient questions and counseling patients about health maintenance are all parts of what we enjoy as rheumatologists, many of these activities can be done outside an appointment by primary care providers or by APPs.

The rheumatology workforce shortage mandates that we view face-to-face time between patient and clinician as a vanishing resource to be conserved for appropriate application to those patients who need it most. So how can we deliver responsive, high-quality care for the right patients—those with active disease in need of intervention—and see fewer patients whose inactive or stable disease may allow them to safely stay home and be seen less frequently?

Digital health technologies provide some answers. We can all agree that technology for technology’s sake is problematic, but technology that solves problems is worth considering. The problem we face is poor access to rheumatologic care, which stems from too few new patient appointment slots. Thus, if technology can help diminish stable follow-up visits while helping maintain a therapeutic doctor-patient relationship, this may be technology worth pursuing.

We have been interested in whether remote patient monitoring via digital technology, such as mobile health apps, could help serve this dual purpose: inform clinicians when visits are needed for active patients and when they can be avoided in stable patients, while allowing providers and patients to remain in contact about symptoms. In essence, the question becomes whether remote assessment of disease activity on a precision basis can allow rheumatic disease providers to effectively manage a larger population of patients than traditional management through face-to-face visits only—precision medicine on a population level.

Knowledge & Communication in an App

In 2018–19, Dr. Solomon collaborated with colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital to test the feasibility of a mobile health app for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) that collects short-form patient-reported outcomes (PROs).7 This process started with user-centered design focus groups and tested different prototypes. The PRO app was tested with 100 patients over 12 months. Patients enjoyed using the app and were relatively compliant (~65%) over one year.8

In focus groups conducted after our study, patients provided further feedback about how often they wanted to answer PROs and which ones were most useful; they also wanted their clinicians to have easy access to their PRO data, as the original version did not integrate with the electronic health record (EHR).

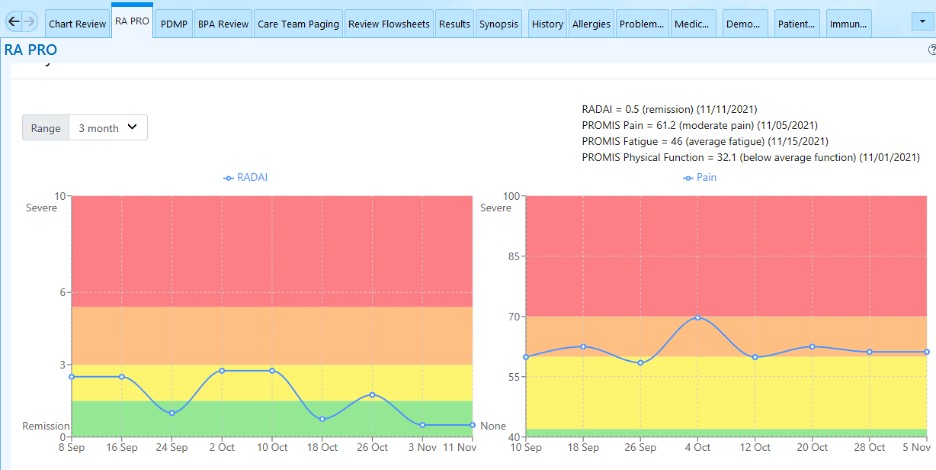

After several years, various iterations, and funding from the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the mobile health PRO app (mPRO) was integrated into the EHR, Epic. Before pursuing this integration, rheumatologists provided advice on how to integrate the PRO data into clinical decision making. This helped decide on how to display the data (see Figure, below), as well as processing the data to provide behavioral nudges to providers.

RheumApp digests the information and lets the responsible clinician know when to consider dynamically rescheduling a patient: If patient-reported symptoms are stable, the app suggests delaying the visit; and if the patient’s symptoms are worsening, the app suggests an early visit. These messages are delivered as secure emails within the EHR.

Over a recent one-year study with 150 RA patients, we observed that the delay visit email was triggered 108 times across almost 443 scheduled visits (24%).8 This suggests that there are a lot of visits for patients with stable PROs. Approximately 20% of delay visit emails resulted in actual delayed visits. The ability to dynamically reschedule stable patients, delaying appointments, could help practices reduce their wait times.

The PRO app is narrowly focused on improving access through dynamic rescheduling, but it serves several other important functions.

First, the continuous collection of PRO data is important to fulfill the goal of treating to target. Access to PRO data between visits means that management decisions can be evidence based with enhanced patient involvement. The PRO data can also be used for value-based care reporting with health plan payers. In fact, the application can support a practice’s participation with Medicare’s MIPS Advancing Rheumatology Care Value Pathway.

Second, the PRO app allows patients to input their rheumatology drugs, reminder times for drug administration, and reasons if dosages were missed. This information, alongside the PRO data, allows practices to participate in remote therapeutic monitoring (RTM). RTM is billable under a relatively new set of CPT codes that encourages more remote care. Although there is little experience with RTM in rheumatology, these billing codes are being used in other areas of medicine.

Further, for qualifying patients, remote capture of PROs can also be used to generate disease-specific data that contributes to chronic care management (CCM). Specifically, PRO data can contribute directly to the development of measurable treatment goals, assessment of symptom management and the periodic review requirements of the comprehensive care plan.

PRO capture can also inform the medical, functional and psychosocial needs assessment required for CCM.

Finally, by summarizing patient symptoms and function, PRO capture can facilitate the communication required between providers in RTM and CCM programs. Both of these can enhance revenues for rheumatologists.

Widened Reach

The experience we describe above with mobile health applications for rheumatology is not isolated. Studies from China, Norway, the U.K., the Netherlands and likely other locations around the globe suggest the potential for the use of apps to enhance rheumatologic care.10,11

Another approach to reducing the demand for rheumatology consultations seeks to improve clinic efficiency through precision scheduling of initial consultations, specifically those requested following a positive ANA test result. These consultations are frequent, rather conservatively estimated at 10–15% of the consultations at some rheumatology practices, but often do not result in the diagnosis of a systemic autoimmune disease because a positive ANA has a low positive predictive value (10–15%) for autoimmune disease.12,13 Accordingly, inappropriate ordering of ANA testing by primary care clinicians has been criticized as wasteful as part of multiple Choose Wisely campaigns.14,15 The recognition of differential risk among those on a rheumatologist’s wait list calls into question the typical first come, first served scheduling paradigm pursued in many U.S. rheumatology clinics.

Efforts to create triage strategies for patients with arthritis based solely on the information contained in referral letters is often inadequate.16,17 A risk model based on machine learning and logistic regression of EHR data, which identifies ANA-positive patients who are at high risk of receiving a systemic autoimmune diagnosis, has been developed and preliminarily validated.18 Of note, a single predictor contributed far greater risk for such a diagnosis than all of the others included in the final model, the presence of a disease-specific autoantibody.

Although indiscriminate referral for positive ANAs is not useful, triage based on the results of disease-specific laboratory testing prior to rheumatology consultation (i.e., pre-consultation laboratory triage) may be worth exploring.19 In adapting this approach, those patients with positive disease-specific results can be scheduled to urgent clinic appointments held open to ensure such patients are seen in a timely manner, while those with negative results remain in the general queue.

Optimizing the performance and accuracy of disease-specific laboratory tests is critical for the success of such triage approaches. Regardless, triaging consultations by priority level ensures that face-to-face consultation time, the vanishing resource of the supply-demand mismatch inherent in the rheumatology workforce shortage, is applied to those patients in greatest need and at highest risk of permanent damage from inordinate wait times.

Another comprehensive approach to facilitate digital health data capture of both PROs and clinically reported outcomes (ClinROs) has been pursued by Specialty Networks Rheumatology. Automated data capture from rheumatology clinic EHR systems generates a database from different sources (i.e., a data lake) which can be queried to provide clinical phenotyping and real-world clinical response insights.20,21 Pairing PRO and ClinRO data allows distinction of between subjective and objective reflections of disease activity and can improve assessments in various rheumatic diseases.22-24 By combining subjective (PRO) and more objective (ClinRO) perspectives, the application of enterprise software generates the opportunity for remote monitoring driven visit schedules coupled with precision treatment of inflammatory vs. noninflammatory symptoms according to dual treat-to-target and triangulated, shared decision making paradigms.25,26 These data are required by rheumatologists to succeed in risk-bearing, value-based care programs with health plan payers.

Finally, a robust dataset can optimize identifying patients at risk for inadequate response or complications and, thereby, the need for more urgent follow-up visits to evaluate for treatment changes, as opposed to those at lower risk who can safely benefit from the convenience of delayed return appointments.

In Sum

In this commentary, we have focused on the promising role of digital health technologies and novel approaches to care that hold promise to improve access to rheumatologic care. Digital health technologies include many other potentially useful devices to enhance remote care: devices to measure joint warmth and appearance, better video visit procedures to enhance examination and history taking, and greater access to electronic consultations.27

Digital health technology also offers new revenue opportunities through reimbursable remote monitoring models (RTM, CCM) to alternative payment models. These may help address the private practice profitability concerns that have been generated by simultaneous and sustained reductions in all three of the traditional sources of practice income: patient encounters, infusions and other ancillary service reimbursement.

Although periodic visits are critical to maintain the therapeutic relationship and confirm PROs, rheumatologists need solutions beyond working more hours; greater embrace of digital health technologies offers possible solutions.

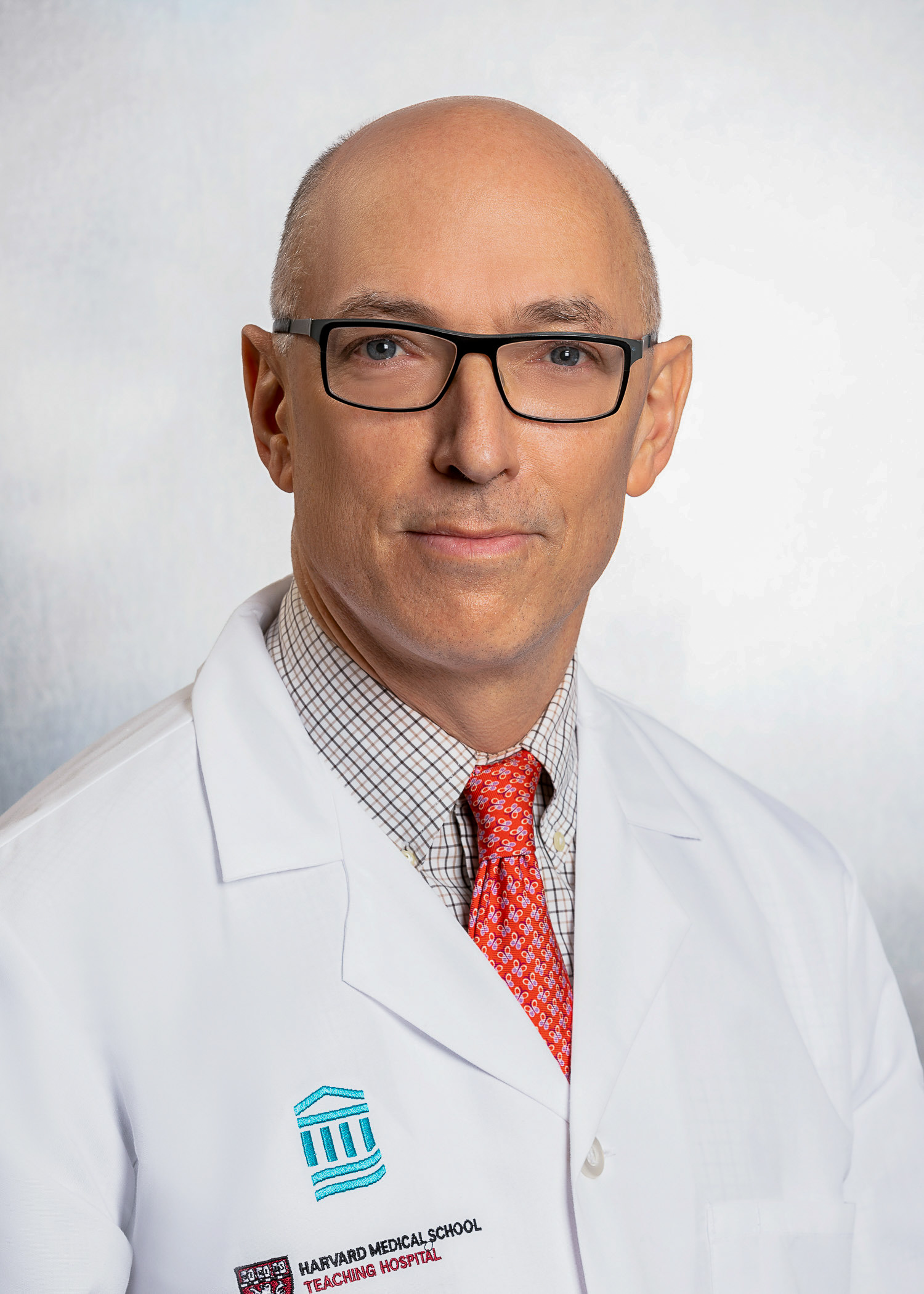

Daniel H. Solomon, MD, MPH, is a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and a member of the Division of Rheumatology and Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, where he holds the Matthew H. Liang Distinguished Chair in Arthritis and Population Health. He has several ongoing projects regarding digital health technologies in rheumatology, attempting to improve the use of patient-reported outcomes in routine practice. He is the editor in chief of Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Andrew Concoff, MD, FACR, is the chief medical officer and chair of the Medical Policy Committee for Specialty Networks/United Rheumatology, where he designs and implements real-world evidence projects and negotiates value-based care arrangements on behalf of rheumatologists with health plans and pharmaceutical manufacturers.

References

- Mannion ML, Xie F, FitzGerald JD, et al. Changes in the workforce characteristics of providers who care for adult patients with rheumatologic and musculoskeletal disease in the United States. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024;76(7):1153–1161.

- Battafarano DF, Ditmyer M, Bolster MB, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology workforce study: Supply and demand projections of adult rheumatology workforce, 2015–2030. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018 Apr;70(4):617–626.

- Dinse GE, Parks CG, Weinberg CR, et al. Increasing prevalence of antinuclear antibodies in the United States. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022 Dec;74(12):2032–2041.

- Duarte-Garcia A, Hocaoglu M, Valenzuela-Almada M, et al. The rising incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus. A population-based study over four decades. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022 Aug;81(9):1260–1266.

- GBD 2021 Rheumatoid Arthritis Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatoid arthritis, 1990–2020, and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023 Sep;5(10):e594–e610.

- The Physicians Foundation. 2024 survey of America’s current and future physicians. 2024 Jul.

- Lee YC, Lu F, Colls J, et al. Outcomes of a mobile app to monitor patient-reported outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 Aug;73(8):1421–1429.

- Colls J, Corrigan C, Suh D, et al. Patient adherence with a smartphone app for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:350–351.

- Solomon DH, Altwies H, Santacroce L, et al. A mobile health application integrated in the electronic health record for rheumatoid arthritis patient-reported outcomes: A controlled interrupted time-series analysis of impact on visit efficiency. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024 May;76:677–683.

- Seppen B, Wiegel J, Ter Wee MM, et al. Smartphone-assisted patient-initiated care versus usual care in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and low disease activity: A randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022 Nov;74(11):1737–1745.

- Berg IJ, Tveter AT, Bakland G, et al. Follow-up of patients with axial spondyloarthritis in specialist health care with remote monitoring and self-monitoring compared with regular face-to-face follow-up visits (the ReMonit study): Protocol for a randomized, controlled open-label noninferiority trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2023 Dec;12:e52872.

- Olsen NJ, Karp DR. Finding lupus in the ANA haystack. Lupus Sci Med. 2020 Feb;7(1): e000384.

- Slater CA, Davis RB, Shmerling RH. Antinuclear antibody testing. A study of clinical utility. Arch Intern Med. 1996 Jul;156(13):1421–1425.

- Qaseem A, Alguire P, Dallas P, et al. Appropriate use of screening and diagnostic tests to foster high-value, cost-conscious care. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jan;156(2):147–149.

- Yazdany J, Schmajuk G, Robbins M, et al. Choosing wisely: The American College of Rheumatology’s top 5 list of things physicians and patients should question. Arthritis Care Res. 2013 Mar;65(3):329–339.

- Jack C, Hazel E, Bernatsky S. Something’s missing here: A look at the quality of rheumatology referral letters. Rheumatol Int. 2012 Apr;32(4):1083–1085.

- Wong J, Tu K, Bernatsky S, et al. Quality and continuity of information between primary care physicians and rheumatologists. BMC Rheumatol. 2019 May:3:1.

- Barnado A, Moore RP, Domenico HJ, et al. Identifying antinuclear antibody positive individuals at risk for developing systemic autoimmune disease: Development and validation of a real-time risk model. Front Immunol. 2024 Mar 20:15:1384229.

- Fitch-Rogalsky C, Steber W, Mahler M, et al. Clinical and serological features of patients referred through a rheumatology triage system because of positive antinuclear antibodies. PLoS ONE. 2014 Apr;9(4): e93812.

- Girman C, Panaccio MP, Hayes K, et al. Pain and fatigue improvements in patients treated with repository corticotropin injection across five indications: A narrative review. Adv Ther. 2022 Jul;39(7):3072–3087.

- Germain G, Worley K, MacKnight SD, et al. Evaluating the real-world effectiveness of belimumab in patients with SLE using SLE-related laboratory values and rheumatoid arthritis-derived disease activity measures: RAPID3, swollen joint count and tender joint count. Lupus Sci Med. 2024 Apr 3;11(1):e001111.

- Eudy AM, Reeve BB, Coles T, et al. The use of patient-reported outcome measures to classify type 1 and 2 systemic lupus erythematosus activity. Lupus. 2022 May; 31(6):697–705.

- Brkic A, Losinska K, Pripp A-H, et al. Remission or not remission, that’s the question: Shedding light on remission and the impact of objective and subjective measures reflecting disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2022 Dec;9(6):1531–1547.

- Boone NW, Sepriano A, van der Kuy P-H, et al. Routine assessment of patient index data 3 (RAPID3) alone is insufficient to monitor disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis in clinical practice. RMD Open. 2019 Nov;5(2):e001050.

- Duarte C, Ferreira RJO, Santos EJF, et al. Treating-to-target in rheumatology: Theory and practice. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2022 Mar;36(1):101735.

- Binder-Fineman P, Dzurilla K, Hsiao B, Fraenkel L. Qualitative exploration of triangulated, shared decision-making in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Dec;71(12):1576–1582.

- Solomon DH, Rudin RS. Digital health technologies: Opportunities and challenges in rheumatology. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020 Sep;16(9):525–535.

Disclosures

Dr. Solomon serves as a consultant to GreenCape Health, a digital health company. He has also received research grants from Amgen, Janssen and CorEvitas.

Dr. Concoff serves as a consultant for UnitedRheumatology, a Specialty Networks Company, a management services organization.