Pulmonary manifestations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) include pleuritis, acute pneumonitis, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary arterial hypertension, shrinking lung syndrome and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH). DAH is a rare, but devastating, complication of SLE, with high mortality rates.

The incidence of DAH in SLE ranges from 0.6% to 5.4%, but the mortality rate is as high as 85.7%, if not treated promptly.1,2 The hemorrhage originates in the interstitial capillaries and alveoli due to immune complex damage of microvasculature.3 This often manifests as hemoptysis, decreased hematocrit and subsequent acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.

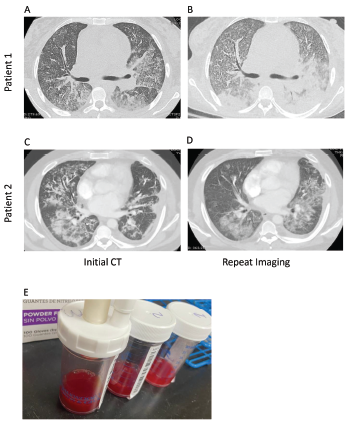

On imaging, findings include diffuse, patchy and groundglass infiltration with characteristic apical and/or peripheral sparing.4,5 Bronchoalveolar lavage provides necessary diagnostic confirmation in which serial bronchoalveolar lavage aspirates are progressively more hemorrhagic, suggesting a capillary or alveolar, as opposed to bronchial, origin of bleeding.3

Among rheumatic diseases, DAH is most frequently associated with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis and SLE.3,5 Although DAH in SLE most commonly presents in the context of multi-organ disease manifestations, DAH can be a harbinger of significant systemic disease in patients with previously controlled, single-organ disease, such as cutaneous lupus.6,7

Here, we present two cases of DAH in patients admitted to the Los Angeles County + University of Southern California (LAC + USC) Medical Center during the COVID-19 surge in early 2021. Comparing and contrasting these two DAH cases provides an opportunity to explore common and uncommon presentations of SLE-associated DAH, while summarizing current literature on prognostic indicators and treatment modalities for DAH in SLE.

Patient 1

Figure 1. Computed tomography (CT) imaging of patient 1’s thorax at initial presentation (A) and two weeks after initial diagnosis prior to initiation of plasmapheresis (B) demonstrate bilateral, basilar consolidations. CT imaging of patient 2’s thorax at initial presentation (C) and at readmission (D) demonstrate consolidations with peripheral sparing. Panel E shows sequential bronchoalveolar lavage aliquots from patient 2, from right to left, that were progressively more hemorrhagic with consecutive fluid washes.

A 26-year-old woman with an unremarkable past medical history presented with two weeks of progressive shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion and chest pain, with associated generalized fatigue and musculoskeletal pain. She described intermittent morning stiffness and pain in both hands for more than 30 minutes over the prior several weeks. She denied photosensitivity, fevers, chills, diarrhea, upper respiratory infection symptoms, night sweats, constipation, hematochezia, hematemesis, menorrhagia or melena. She also denied contact with anyone sick and recent travel. She reported that her menses were regular and without change in character.

In the emergency department, she was afebrile and normotensive, but was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 115 beats per minute and hypoxic, with an oxygen saturation of 87% on room air, requiring oxygen supplementation by nasal cannula. COVID-19 nasal swab testing was negative.

Initial laboratory testing revealed anemia, leukocytosis, increased creatinine and hyperkalemia (see Table 1). Urinalysis demonstrated microscopic hematuria and proteinuria. A chest X-ray revealed multifocal opacities, and bedside ultrasound demonstrated small pleural effusions and a pericardial effusion.

Given the presentation of a heretofore healthy young woman with fatigue, anemia, renal impairment, proteinuria, pleural effusions and pericardial effusions, a systemic inflammatory disorder was high on the differential diagnosis.

Additional laboratory studies revealed decreased C3 and C4, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibody, anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies. An evaluation for infection, including viral nasopharyngeal screening, bacterial and fungal blood cultures, and viral and fungal serologies, was unrevealing.

Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax revealed extensive bilateral, consolidative and groundglass opacities, most prominent in the lower lobes, along with trace bilateral pleural effusions, mild cardiomegaly, a small pericardial effusion and multiple large axillary and mediastinal lymph nodes (see Figures 1a and b). CT angiography was not performed due to renal dysfunction.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed an ejection fraction of 60–65% and a small to moderate pericardial effusion without evidence of tamponade or elevated right-heart pressures.

Renal ultrasound demonstrated bilateral kidneys with normal shape, size and echogenicity with no hydronephrosis. Renal biopsy demonstrated diffuse glomerulonephritis and endocapillary hypercellularity, with 55% cellular crescents, consistent with highly active ISN/RPS class IV lupus nephritis, without evidence of vasculitis.

DAH was documented through bronchoalveolar lavage with increasingly bloody aspirates in serial lavage washings.

Persistent hemoptysis (i.e., <100 mL, daily, for three to five days) not only led to the need for intermittent blood transfusions, but also resulted in worsening oxygenation that required supplementation via high-flow nasal cannula and intubation for 24 hours.

Initial treatment with 1 g of intravenous (IV) pulse methylprednisolone daily for three days, 1.5 g of IV cyclophosphamide and inhaled tranexamic acid failed to control the hemoptysis or improve oxygenation. The addition of five sessions of plasmapheresis, 2 g/kg of IV immunoglobulins (IVIG) over five days, and 1 g of rituximab was needed to control the hemorrhage.

The patient was successfully weaned from high-flow nasal cannula to room air by hospital day 31 and is doing well clinically, without further hemoptysis. She is currently maintained on prednisone, rituximab, mycophenolate mofetil and hydroxychloroquine. Cyclophosphamide has been discontinued due to concern for hemorrhagic cystitis.