DAH can be a harbinger of significant systemic disease in patients with previously controlled, single-organ disease, such as cutaneous lupus.

Lower extremity Doppler ultrasound revealed an acute deep venous thrombosis of the right popliteal vein. In the emergency department, he developed progressive hypoxia and worsening tachypnea, requiring supplemental oxygen via high-flow nasal cannula, and eventual intubation, for acute hypoxic respiratory failure. His course was complicated by the pulseless electrical activity, which required two rounds of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and initiation of inotropic support.

Emergency bronchoscopy demonstrated active DAH, and plasmapheresis was initiated.

During this second hospitalization, the patient received aerosolized tranexamic acid, high-dose methylprednisolone, a second infusion of 1 g cyclophosphamide, two 1 g infusions of rituximab and five plasmapheresis sessions.

His course was complicated by multiple episodes of hematemesis that necessitated multiple blood transfusions and by development of cytomegalovirus viremia. An inferior vena cava filter was placed because he developed a right lower extremity deep vein thrombosis and could not be treated with anticoagulation due to ongoing hemorrhage.

Due to extended ventilatory support requirements, he underwent tracheostomy and was eventually weaned to room air after 24 days of mechanical and mask support.

After 33 days of hospitalization, the patient was transferred to acute rehabilitation and subsequently discharged home. His clinical improvement has been significant, with decannulation of his tracheostomy and no further hemoptysis. His outpatient maintenance regimen includes prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil and hydroxychloroquine, with a plan for further rituximab. Renal biopsy is being considered to evaluate for suspected lupus nephritis.

Discussion

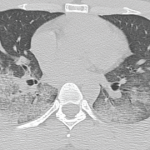

These two cases of SLE-associated DAH include both common and uncommon features of DAH. Patient 1 had a common presentation of DAH in that she was a female patient in whom new-onset SLE presented as multi-organ disease manifestations with DAH and glomerulonephritis.3,5,6 Common features from patient 2 include characteristic imaging findings of DAH, specifically with pulmonary consolidations that included apical and peripheral sparing (see Figures 1c and d).4

On the other hand, an uncommon feature in patient 1 is that her CT imaging revealed consolidations without peripheral sparing (see Figure 1). Patient 2 had an uncommon presentation of DAH in that, although the median time to diagnosis of lupus to systemic disease is one to two years, his time to development of end-organ disease was 10 years.8

The progression from SLE with primarily cutaneous features to systemic involvement typically includes manifestations of nephritis, serositis, photosensitivity, malar rash, oral ulcers, arthritis, neurologic disease and hematologic disorders.8 DAH is not often associated with cutaneous to systemic lupus disease progression.7

DAH, whether or not due to SLE, is a catastrophic disease that demands prompt treatment, as evidenced in these cases. However, other pulmonary diseases, including pulmonary embolism, pleuritis, infections, cardiac valvular diseases, pulmonary hypertension and catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome must be considered—and, if present, must be concurrently treated.1,3,5

Current knowledge regarding mortality in SLE-associated DAH and the ideal treatment strategy for this condition stem largely from single case reports or case series. Recently, Jiang et al. collated 251 patients from eight studies encompassing cases of SLE-associated DAH and determined through a meta-analysis that older age at DAH diagnosis, increased SLE disease duration, requirement for plasmapheresis or mechanical ventilation, and concurrent infection are risk factors associated with poor survival.5

Other studies have noted active lupus nephritis, hypoalbuminemia and thrombocytopenia as poor prognostic factors.3,6

Treatment of DAH focuses on countering the autoimmune destruction of the alveolar capillaries and implementing protective strategies, including supplemental oxygen, reversal of coagulopathy, achievement of hemostasis and possible intubation.

Treatment of the underlying hemorrhage, which may manifest not only as hemoptysis, but also as hematemesis and/or an acute drop in hemoglobin, with methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide, is often prudent; in addition, plasmapheresis and rituximab are often used.3