Pulmonary manifestations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) include pleuritis, acute pneumonitis, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary arterial hypertension, shrinking lung syndrome and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH). DAH is a rare, but devastating, complication of SLE, with high mortality rates.

The incidence of DAH in SLE ranges from 0.6% to 5.4%, but the mortality rate is as high as 85.7%, if not treated promptly.1,2 The hemorrhage originates in the interstitial capillaries and alveoli due to immune complex damage of microvasculature.3 This often manifests as hemoptysis, decreased hematocrit and subsequent acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.

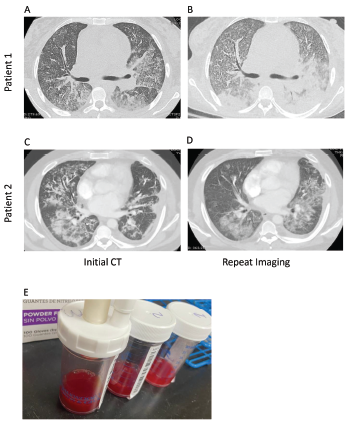

On imaging, findings include diffuse, patchy and groundglass infiltration with characteristic apical and/or peripheral sparing.4,5 Bronchoalveolar lavage provides necessary diagnostic confirmation in which serial bronchoalveolar lavage aspirates are progressively more hemorrhagic, suggesting a capillary or alveolar, as opposed to bronchial, origin of bleeding.3

Among rheumatic diseases, DAH is most frequently associated with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis and SLE.3,5 Although DAH in SLE most commonly presents in the context of multi-organ disease manifestations, DAH can be a harbinger of significant systemic disease in patients with previously controlled, single-organ disease, such as cutaneous lupus.6,7

Here, we present two cases of DAH in patients admitted to the Los Angeles County + University of Southern California (LAC + USC) Medical Center during the COVID-19 surge in early 2021. Comparing and contrasting these two DAH cases provides an opportunity to explore common and uncommon presentations of SLE-associated DAH, while summarizing current literature on prognostic indicators and treatment modalities for DAH in SLE.

Patient 1

Figure 1. Computed tomography (CT) imaging of patient 1’s thorax at initial presentation (A) and two weeks after initial diagnosis prior to initiation of plasmapheresis (B) demonstrate bilateral, basilar consolidations. CT imaging of patient 2’s thorax at initial presentation (C) and at readmission (D) demonstrate consolidations with peripheral sparing. Panel E shows sequential bronchoalveolar lavage aliquots from patient 2, from right to left, that were progressively more hemorrhagic with consecutive fluid washes.

A 26-year-old woman with an unremarkable past medical history presented with two weeks of progressive shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion and chest pain, with associated generalized fatigue and musculoskeletal pain. She described intermittent morning stiffness and pain in both hands for more than 30 minutes over the prior several weeks. She denied photosensitivity, fevers, chills, diarrhea, upper respiratory infection symptoms, night sweats, constipation, hematochezia, hematemesis, menorrhagia or melena. She also denied contact with anyone sick and recent travel. She reported that her menses were regular and without change in character.

In the emergency department, she was afebrile and normotensive, but was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 115 beats per minute and hypoxic, with an oxygen saturation of 87% on room air, requiring oxygen supplementation by nasal cannula. COVID-19 nasal swab testing was negative.

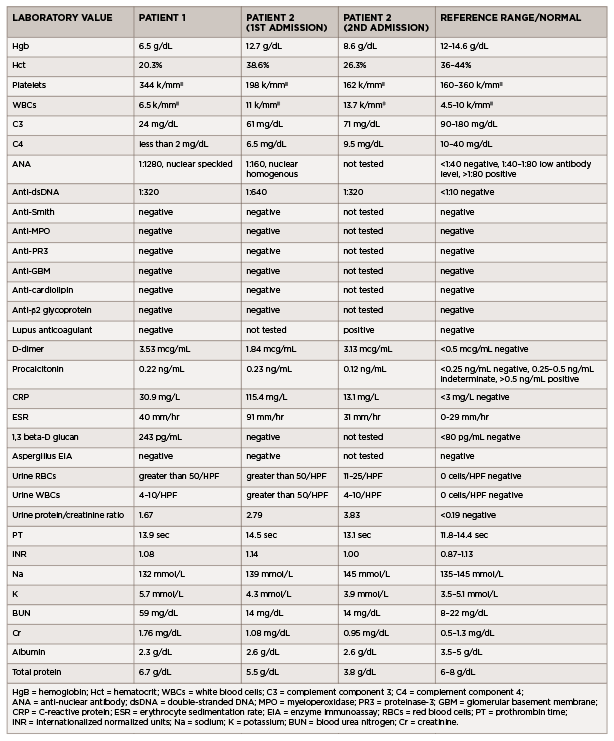

Initial laboratory testing revealed anemia, leukocytosis, increased creatinine and hyperkalemia (see Table 1). Urinalysis demonstrated microscopic hematuria and proteinuria. A chest X-ray revealed multifocal opacities, and bedside ultrasound demonstrated small pleural effusions and a pericardial effusion.

Given the presentation of a heretofore healthy young woman with fatigue, anemia, renal impairment, proteinuria, pleural effusions and pericardial effusions, a systemic inflammatory disorder was high on the differential diagnosis.

Additional laboratory studies revealed decreased C3 and C4, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibody, anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies. An evaluation for infection, including viral nasopharyngeal screening, bacterial and fungal blood cultures, and viral and fungal serologies, was unrevealing.

Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax revealed extensive bilateral, consolidative and groundglass opacities, most prominent in the lower lobes, along with trace bilateral pleural effusions, mild cardiomegaly, a small pericardial effusion and multiple large axillary and mediastinal lymph nodes (see Figures 1a and b). CT angiography was not performed due to renal dysfunction.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed an ejection fraction of 60–65% and a small to moderate pericardial effusion without evidence of tamponade or elevated right-heart pressures.

Renal ultrasound demonstrated bilateral kidneys with normal shape, size and echogenicity with no hydronephrosis. Renal biopsy demonstrated diffuse glomerulonephritis and endocapillary hypercellularity, with 55% cellular crescents, consistent with highly active ISN/RPS class IV lupus nephritis, without evidence of vasculitis.

DAH was documented through bronchoalveolar lavage with increasingly bloody aspirates in serial lavage washings.

Persistent hemoptysis (i.e., <100 mL, daily, for three to five days) not only led to the need for intermittent blood transfusions, but also resulted in worsening oxygenation that required supplementation via high-flow nasal cannula and intubation for 24 hours.

Initial treatment with 1 g of intravenous (IV) pulse methylprednisolone daily for three days, 1.5 g of IV cyclophosphamide and inhaled tranexamic acid failed to control the hemoptysis or improve oxygenation. The addition of five sessions of plasmapheresis, 2 g/kg of IV immunoglobulins (IVIG) over five days, and 1 g of rituximab was needed to control the hemorrhage.

The patient was successfully weaned from high-flow nasal cannula to room air by hospital day 31 and is doing well clinically, without further hemoptysis. She is currently maintained on prednisone, rituximab, mycophenolate mofetil and hydroxychloroquine. Cyclophosphamide has been discontinued due to concern for hemorrhagic cystitis.

(click for larger image) Table 1: Laboratory Values (all values listed are from the day of admission)

Patient 2

A 35-year-old man with previously well-controlled systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) with cutaneous features presented with four days of myalgias, generalized fatigue, rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, productive cough with white sputum and subjective fevers, followed by one day of <100 mL of hemoptysis.

He reported no shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, nausea, vomiting, hematuria, dysuria, sick contacts or recent travel. His past medical history was noteworthy for having completed latent tuberculosis treatment for a positive, purified-protein-derivative skin test in 2000 and a hospital admission in April 2019 for cough and shortness of breath. During that admission, he was found to have an exudative pleural effusion with numerous neutrophils, histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Pulmonary tuberculosis was ruled out, and his illness was attributed to an undefined infection.

The patient was diagnosed in 2008 with lupus with rash, arthritis, hypocomplementemia, thrombocytopenia, positive ANA, positive anti-dsDNA antibody and anti-Smith antibody. His symptoms had been controlled from 2008 to late 2019 with hydroxychloroquine and low-dose prednisone. However, in late 2019, he developed Raynaud’s phenomenon and proteinuria, and was started on mycophenolate mofetil, with limited adherence. At the time of his presentation in early 2021, he had been consistently taking only prednisone and hydroxychloroquine.

In the emergency department, he was afebrile and normotensive, but tachycardic, with a heart rate of 130 beats per minute. His oxygen saturation was 97% on room air, and his COVID-19 nasal swab testing was negative. Initial laboratory testing revealed leukocytosis (see Table 1).

A chest X-ray demonstrated left middle lobe consolidation with a left pleural effusion. Thoracentesis yielded exudative fluid with numerous neutrophils, histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Bacterial and fungal cultures from this fluid were negative.

Additional laboratory studies revealed microscopic hematuria, pyuria, proteinuria, hypocomplementemia, positive ANA, positive anti-dsDNA antibody, lupus anticoagulant, elevated C-reactive protein and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. An evaluation for infection, including viral serologies, fungal serum markers, bacterial and fungal blood cultures, and pleural fluid bacterial and fungal cultures, did not reveal an infectious etiology.

A CT of the chest revealed extensive bilateral, perihilar, patchy opacities, patent central airways and areas of bilateral consolidation with groundglass opacities and peripheral sparing.

Bronchoalveolar lavage confirmed the diagnosis of DAH, with increasingly bloody aspirates on serial washings (see Figure 1).

The patient was treated with IV pulse methylprednisolone for three days, with subsequent taper, and one dose of 1 g IV cyclophosphamide. He remained hemodynamically stable on room air throughout his hospital course and never required blood transfusions. He was discharged on oral prednisone daily and hydroxychloroquine, with a plan for monthly IV cyclophosphamide.

One week following discharge, he returned to the emergency department with multiple episodes of hemoptysis and worsening respiratory symptoms. He was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 120 beats per minute and tachypneic, breathing at 22 breaths per minute, with an oxygen saturation of 82% on room air.

His chest X-ray showed slight interval improvement, but a CT pulmonary angiogram demonstrated multiple acute pulmonary emboli, along with extensive multifocal airspace consolidations in both lungs.

DAH can be a harbinger of significant systemic disease in patients with previously controlled, single-organ disease, such as cutaneous lupus.

Lower extremity Doppler ultrasound revealed an acute deep venous thrombosis of the right popliteal vein. In the emergency department, he developed progressive hypoxia and worsening tachypnea, requiring supplemental oxygen via high-flow nasal cannula, and eventual intubation, for acute hypoxic respiratory failure. His course was complicated by the pulseless electrical activity, which required two rounds of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and initiation of inotropic support.

Emergency bronchoscopy demonstrated active DAH, and plasmapheresis was initiated.

During this second hospitalization, the patient received aerosolized tranexamic acid, high-dose methylprednisolone, a second infusion of 1 g cyclophosphamide, two 1 g infusions of rituximab and five plasmapheresis sessions.

His course was complicated by multiple episodes of hematemesis that necessitated multiple blood transfusions and by development of cytomegalovirus viremia. An inferior vena cava filter was placed because he developed a right lower extremity deep vein thrombosis and could not be treated with anticoagulation due to ongoing hemorrhage.

Due to extended ventilatory support requirements, he underwent tracheostomy and was eventually weaned to room air after 24 days of mechanical and mask support.

After 33 days of hospitalization, the patient was transferred to acute rehabilitation and subsequently discharged home. His clinical improvement has been significant, with decannulation of his tracheostomy and no further hemoptysis. His outpatient maintenance regimen includes prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil and hydroxychloroquine, with a plan for further rituximab. Renal biopsy is being considered to evaluate for suspected lupus nephritis.

Discussion

These two cases of SLE-associated DAH include both common and uncommon features of DAH. Patient 1 had a common presentation of DAH in that she was a female patient in whom new-onset SLE presented as multi-organ disease manifestations with DAH and glomerulonephritis.3,5,6 Common features from patient 2 include characteristic imaging findings of DAH, specifically with pulmonary consolidations that included apical and peripheral sparing (see Figures 1c and d).4

On the other hand, an uncommon feature in patient 1 is that her CT imaging revealed consolidations without peripheral sparing (see Figure 1). Patient 2 had an uncommon presentation of DAH in that, although the median time to diagnosis of lupus to systemic disease is one to two years, his time to development of end-organ disease was 10 years.8

The progression from SLE with primarily cutaneous features to systemic involvement typically includes manifestations of nephritis, serositis, photosensitivity, malar rash, oral ulcers, arthritis, neurologic disease and hematologic disorders.8 DAH is not often associated with cutaneous to systemic lupus disease progression.7

DAH, whether or not due to SLE, is a catastrophic disease that demands prompt treatment, as evidenced in these cases. However, other pulmonary diseases, including pulmonary embolism, pleuritis, infections, cardiac valvular diseases, pulmonary hypertension and catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome must be considered—and, if present, must be concurrently treated.1,3,5

Current knowledge regarding mortality in SLE-associated DAH and the ideal treatment strategy for this condition stem largely from single case reports or case series. Recently, Jiang et al. collated 251 patients from eight studies encompassing cases of SLE-associated DAH and determined through a meta-analysis that older age at DAH diagnosis, increased SLE disease duration, requirement for plasmapheresis or mechanical ventilation, and concurrent infection are risk factors associated with poor survival.5

Other studies have noted active lupus nephritis, hypoalbuminemia and thrombocytopenia as poor prognostic factors.3,6

Treatment of DAH focuses on countering the autoimmune destruction of the alveolar capillaries and implementing protective strategies, including supplemental oxygen, reversal of coagulopathy, achievement of hemostasis and possible intubation.

Treatment of the underlying hemorrhage, which may manifest not only as hemoptysis, but also as hematemesis and/or an acute drop in hemoglobin, with methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide, is often prudent; in addition, plasmapheresis and rituximab are often used.3

Conclusion

SLE-associated DAH is not yet adequately understood. Multicenter studies to define ideal diagnosis and treatment strategies for patients are sorely needed. Prompt recognition of the disease, appropriate supportive therapy and informed immunosuppressive interventions improve outcomes for patients with SLE-associated DAH.

Abhimanyu Amarnani, MD, PhD, is an internal medicine resident in the ABIM Research Pathway at Los Angeles County + University of Southern California Medical Center and the Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California (USC), Los Angeles, and is pursuing a fellowship in rheumatology.

Abhimanyu Amarnani, MD, PhD, is an internal medicine resident in the ABIM Research Pathway at Los Angeles County + University of Southern California Medical Center and the Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California (USC), Los Angeles, and is pursuing a fellowship in rheumatology.

Nicole K. Zagelbaum Ward, DO, MPH, is a second-year rheumatology fellow at the Keck School of Medicine, USC.

Nicole K. Zagelbaum Ward, DO, MPH, is a second-year rheumatology fellow at the Keck School of Medicine, USC.

Lauren Mathias, MD, is an attending physician at PIH Health Hospital in Downey, Calif. Her interests include general rheumatology, musculoskeletal ultrasound and medical education.

Lauren Mathias, MD, is an attending physician at PIH Health Hospital in Downey, Calif. Her interests include general rheumatology, musculoskeletal ultrasound and medical education.

Nathan Lim, MD, is a second-year rheumatology fellow at USC.

Nathan Lim, MD, is a second-year rheumatology fellow at USC.

Baljeet Rai, MD, is a third-year internal medicine resident at USC, pursuing a career in rheumatology.

Baljeet Rai, MD, is a third-year internal medicine resident at USC, pursuing a career in rheumatology.

Sky Wang, MD, is an attending physician in the Section of Rheumatology at the Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, Los Angeles.

Sky Wang, MD, is an attending physician in the Section of Rheumatology at the Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center, Los Angeles.

William Stohl, MD, PhD, is professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Rheumatology at the Keck School of Medicine, USC.

William Stohl, MD, PhD, is professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Rheumatology at the Keck School of Medicine, USC.

References

- Zamora MR, Warner ML, Tuder R, et al. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical presentation, histology, survival, and outcome. Medicine (Baltimore). 1997 May;76(3):192–202.

- Mintz G, Galindo LF, Fernández-Diez J, et al. Acute massive pulmonary hemorrhage in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. Spring 1978;5(1):39–50.

- Al-Adhoubi NK, Bystrom J. Systemic lupus erythematosus and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, etiology and novel treatment strategies. Lupus. 2020 Apr;29(4):355–363.

- Marten K, Schnyder P, Schirg E, et al. Pattern-based differential diagnosis in pulmonary vasculitis using volumetric CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005 Mar;

184(3):720–733. - Jiang M, Chen R, Zhao L, et al. Risk factors for mortality of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021 Feb 16;23(1):57.

- Sun Y, Zhou C, Zhao J, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus–associated diffuse alveolar hemorrhage: A single-center, matched case-control study in China. Lupus. 2020 Jun;29(7):795–803.

- Vilá-Rivera K, Jiménez-Encarnación E, Vilá S. Pulmonary hemorrhage in a patient initially presenting with discoid lupus. P R Health Sci J. 2013 Dec;32(4):203–205.

- Elman SA, Joyce C, Costenbader KH, et al. Time to progression from discoid lupus erythematosus to systemic lupus erythematosus: A retrospective cohort study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020 Jan;45(1):89–91.