SAN DIEGO—Kawasaki disease (KD) is not going away. These words, spoken by Jane C. Burns, MD, director of the Kawasaki Disease Research Center in the department of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, in La Jolla, set the context and tone for a session at the 2013 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, held October 26–30. [Editor’s Note: This session was recorded and is available via ACR SessionSelect at www.rheumatology.org.] The session was devoted to providing rheumatologists with tools to recognize and treat KD.

Citing unpublished epidemiological data from Japan, Dr. Burns highlighted that almost 14,000 new cases of KD were diagnosed in 2012 and that one in every 85 children in Japan is predicted to develop KD during the first 10 years of life. In the United States, she said, it is estimated that one in 1,600 adults will have had KD by 2030.

During the session, entitled “Kawasaki Disease: Putting Out the Fire,” a panel of experts provided updated information on the diagnosis and treatment of KD with an emphasis on the need for early detection to minimize complications, including the potential for the formation of coronary artery aneurysms.

Kawasaki Disease: What It Is and What It Is Not

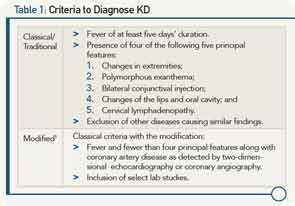

Knowing how to recognize KD and make the differential diagnosis from other diseases is not easy, and requires familiarity with an evolving understanding of what the disease is, according to Robert Sundel, MD, program director in rheumatology at Boston Children’s Hospital, and associate professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School in Boston. He emphasized the limitations of the classic or traditional criteria once used to diagnose KD, and discussed more recently developed modified criteria that expanded the differential diagnosis of KD (see Table 1).

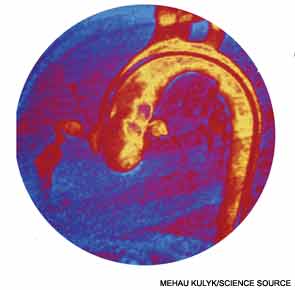

Among key features that led to formulation of the modified criteria was the recognition that many patients with KD have concurrent infections, complicating determination of which other conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis. Further, evolving recognition of cardiac involvement in patients who do not meet classical criteria for KD necessitated alternative approaches to optimize outcomes. Occult cardiac involvement in patients with KD includes myocarditis and, importantly, coronary artery aneurysms, he said, emphasizing that the presence of cardiac involvement is a major prognostic determinant with a mortality rate of 1.5% in untreated patients that falls to less than 0.1% in treated patients.

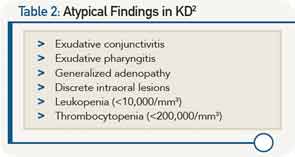

The modified criteria can be used to diagnose most patients, including a large percentage of the 20% to 60% of children who develop aneurysms but never meet KD criteria. Further work is needed to develop criteria to identify patients at risk for these aneurysms and tailor therapy accordingly. He emphasized that many cases of KD include unusual features such as shock physiology or acute abdominal symptoms. Among the most helpful information for clinicians trying to diagnose KD is to recognize certain findings that are seldom seen in KD (see Table 2).

Overall, he urged clinicians to keep KD in mind when seeing any febrile child and to approach diagnosis by ruling out KD. He emphasized the need for early, aggressive treatment before coronary aneurysms occur and the need for agents that can safely protect coronary arteries.

Treatment Options

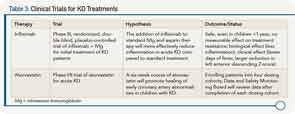

Dr. Burns reviewed clinical trial data on new treatments for KD (see Table 3).

Based on the data, she said that infliximab should be considered in children with high inflammation and those with early coronary artery changes. “A single dose of infliximab (5 mg/kg) is safe and well tolerated in patients with acute Kawasaki disease and reduces fever, inflammation, and coronary artery internal diameter faster,” she said.

Although data on atorvastatin is still pending, Dr. Burns emphasized that statins may hold promise for mitigating coronary artery damage in the acute phase.

She also presented data from the San Diego Adult KD Collaborative study that is beginning to address the future of KD patients and cardiovascular health by looking at the effect of KD on future cardiovascular health, the risk (if any) for people with normal echocardiograms during acute illness, and the feasibility of stratifying patients based on risk using simple, noninvasive tests. Results of one study published in 2012 that looked at computed tomography (CT) calcium scores in KD patients years after KD diagnosis found no calcification in patients with a history of KD and normal coronary arteries during the acute phase of the disease, and found that coronary calcification, which may be severe, occurs late in patients with coronary aneurysms.3 These results suggest, according to Dr. Burns, the usefulness of CT calcium scoring to screen patients with a remote history of KD or suspected KD and unknown coronary artery status.

Based on what is currently known from the Adult KD Collaborative study, Dr. Burns feels strongly that all patients with any coronary artery abnormality should be followed for life by a cardiologist with knowledge of KD vasculopathy. More controversial, she said, is whether patients with normal echocardiograms throughout their initial course of KD need follow up by a cardiologist.

Finding the right therapy to give children with early coronary artery abnormalities to prevent progression to aneurysm formation remains a key challenge in treating KD, she said.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical journalist based in St. Paul, Minn.

References

- Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber, MA, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki Disease. Circulation. 2004;110:2747-2771.

- Koren G, Silverman E, Sundel R, et al. Decreased protein binding of salicylates in Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 1991;118:456-459.

- Kahn AM, Budoff MJ, Daniels LB, et al. Calcium scoring in patients with a history of Kawasaki disease. JACC Imaging. 2012;5:264-272.