SAN DIEGO—For patients with inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis (RA), eye complications are a serious event that may lead to vision loss. A rheumatologist and an ophthalmologist/internist updated their colleagues on diagnosing and treating these potential threats at the 2013 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, held October 26–30. [Editor’s Note: This session was recorded and is available via ACR SessionSelect at www.rheumatology.org.]

Uveitis is an inflammation of any part of the uveal tract and is a serious potential complication of systemic autoimmune diseases, said George N. Papaliodis, MD, director of the ocular immunology and uveitis service at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary in Boston. “Ocular inflammatory disease is the third-leading cause of blindness worldwide, and 35% of patients with uveitis have some type of visual impairment. The eye does not tolerate inflammation well,” he said. In addition, inflammatory eye disease “is an incredibly difficult and expensive disease to treat.” For example, a recent look of HLA-B27–associated uveitis showed that the annual average cost to treat this disease is $4,108.60, he noted. Nationwide medical claims figures for treating uveitis-associated blindness were more than $240 million in 2003.

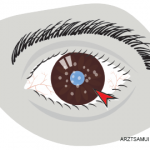

Any layer of the eye may be involved in ocular inflammation, said Dr. Papaliodis. Common forms include iritis, or inflammation of the anterior portion of the eye; choroiditis; episcleritis; scleritis; keratitis; papillitis; and vitritis. Although trauma or medications can cause uveitis, HLA-B27 is the most common cause for recurrent iritis in the U.S. “Approximately two-thirds of these patients have underlying systemic disease causing the problem,” said Dr. Papaliodis.

Rheumatologists should always consider autoimmune eye disease as a potential complication in their patients, he said. “My staunch position is that there is no such thing as a standard uveitis workup.” The selection of laboratory studies or radiographic imaging should be guided by the patient’s clinical examination and associated symptoms, he added.

In patients with HLA-B27–related diseases, rheumatologists can diagnose the most common inflammatory eye complication, iritis, in the office. “Permanent ophthalmic damage may result not only from the underlying disease complications, but from the most common treatments, like corticosteroids,” he noted. Cataracts, glaucoma, and cystoid macular edema are three potential complications of iritis, and cataracts and glaucoma also may be related to corticosteroid use.

Although most cases are idiopathic, up to one-third of cases of episcleritis, an inflammation of the thin layer of tissue between the conjunctiva and the sclera, are related to underlying systemic diseases like RA, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis, he said. Treatments include artificial tears and oral nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, but topical steroid drops, although effective, are rarely used as patients may develop complications from the drops, Dr. Papaliodis noted.

In scleritis, a rarer condition, almost 60% of cases are due to underlying systemic associations. Rheumatologists must consider scleritis as a possible complication of RA, SLE, ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and Sjögren’s syndrome. Diagnosis includes tactile stimulation resulting in increased pain sensation, and therapies may include systemic corticosteroids and potentially steroid-sparing immunomodulatory therapy depending upon the severity of disease and chronicity of ocular inflammation.

There are some cases of masquerading syndromes that appear to be inflammatory eye disease but are not, Dr. Papaliodis said. Some conditions that can mimic intraocular inflammation include malignancy and ocular infections, he said.

Collaborating with Colleagues

Although rheumatologists are comfortable diagnosing systemic diseases, they may be uncomfortable evaluating the eyes of their patients, said Sergio Schwartzman, MD, associate attending rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City. “I believe this is an area where there should be a very close marriage between the rheumatologist and the ophthalmologist, or else patients will suffer,” he stressed.

To diagnose uveitis, a thorough medical history and physical examination, including a slitlamp exam, are most important, Dr. Schwartzman said. An ophthalmologist with experience in treating autoimmune eye diseases should also participate in these patients’ care, he added. Rheumatologists should, at minimum, test for syphilis and tuberculosis, conduct a baseline chest X-ray and routine laboratory tests, and evaluate the patient for Lyme disease. Further testing would be based on the patient’s history and physical exam, he said.

Rheumatologists have various challenges in treating their patients who present with these conditions, Dr. Schwartzman said. It is likely that studies of various therapies in autoimmune eye diseases are limited by low patient numbers and trial design. Many ophthalmologists treat uveitis with prolonged corticosteroid therapy, but there is some early evidence to support use of immunosuppressive and remittive medications earlier, he said. In a condition like acute anterior uveitis, which is rarely seen by rheumatologists except in patients with spondylarthropathies, topical steroid drops typically treat the uveitis successfully.

Remittive medications used to treat recalcitrant or “resistant” uveitis include methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and, rarely, cyclophosphamide. There are few prospective, randomized studies on these therapies and even fewer head-to-head trials, he said. The First-line Antimetabolites as Steroid-sparing Treatment uveitis pilot trial (FAST) was designed to compare oral mycophenolate mofetil with oral methotrexate in uveitis patients who needed corticosteroid-sparing therapy. Results are not yet published.

Other options for treating uveitis include intraocular drug delivery methods such as implants, which bypass the ocular barrier and have become increasingly successful. However, as these are corticosteroid implants, glaucoma and cataracts are possible complications, he noted.

Recent research shows that different inflammatory cytokines often are found in the ocular fluid of patients with uveitis, Dr. Schwartzman said. Biologic drugs may be a viable treatment option for rheumatologists whose patients have resistant eye disease. Daclizumab, infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept have all been the focus of small clinical trials, but further and better studies are needed to measure their efficacy in these conditions, Dr. Schwartzman said. Monoclonal anti–tumor necrosis factor agents seem to provide some benefit, and infliximab is approved in Japan for Behçet’s-associated uveo-retinitis. Gevokizumab, which binds to interleukin (IL) 1β, was recently given orphan drug designation for noninfectious forms of uveitis. Newer therapies on the horizon include apremilast, tofacitinib, and anti–IL-2 and anti–IL-1 inhibitors.

“The spectrum of autoimmune, systemic diseases that affect the eye is very interesting and quite varied,” Dr. Schwartzman concluded. “Although the armamentarium of therapies available is robust and rapidly expanding, our understanding of the basic pathophysiology of this group of diseases will ultimately be necessary to prevent the unfortunate complications of inflammatory disease of the eye.”

Susan Bernstein is a writer based in Atlanta.