BOSTON—Children and adolescents with pediatric rheumatic diseases may be at increased risk for fractures and low bone-mass density, and rheumatologists should watch for signs of broken bones even in asymptomatic patients, an expert on pediatric rheumatic disease treatment told attendees at the ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting in Boston on Nov. 18, 2014.

Speaking on, Protecting Bone Health in Pediatric Rheumatic Diseases, Jon “Sandy” Burnham, MD, MSCE, clinical director of the Division of Rheumatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, explored how bones develop and where problems may occur in kids in this patient population. Rheumatologists treating pediatric patients should appreciate the contributions of inflammation, glucocorticoid therapy and an altered body composition to lower bone mass and elevated fracture risk in this population, he said.

Careful monitoring, DXA and other imaging techniques, and bisphosphonates may help some pediatric rheumatic disease patients reduce fracture risk, Dr. Burnham said. Bisphosphonates are not FDA approved for use in pediatric patients, he noted.

Dr. Burnham began with the “cautionary tale” of one of his juvenile dermatomyositis patients, a 7-year-old girl who developed severe pain in her back and thigh two months after improving on her initial combination therapy, which included DMARDs and glucocorticoids. An MRI scan of her back revealed epidural lipomatosis and several vertebral compression fractures. Her steroids were tapered, and she was offered bisphosphonates, although her family initially rejected this treatment option, Dr. Burnham said.

Very Strong Structures

“Bones serve a variety of functions,” said Dr. Burnham. They are a bank for minerals, protect our internal organs and support our bodies’ movements with the minimum possible mass. “They are very strong structures. Even with the stupid risk-taking behaviors we all do as children, they really should not break.” Although most kids with rheumatic diseases will not experience a fracture, rheumatologists should watch for vertebral compression fractures even in patients who are asymptomatic, he said.

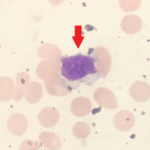

Several factors contribute to normal growth and skeletal development during childhood. Important bone boosters include normal nutrition, with recommended levels of vitamin D and calcium, and weight-bearing physical activity. “Bone adapts mechanical forces to maintain strain at a constant set point,” he said. Osteocytes sense the strain of activities and send effector signals that lead to the production of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, which regulate bone modeling.

Pediatric rheumatic disease patients face some unique challenges to healthy bone development, said Dr. Burnham.

“Pubertal delay is an important factor in peak bone mass. The later the onset of puberty, the lower your peak bone mass,” said Dr. Burnham. Glucocorticoid therapy may also reduce their sex steroids, muscle mass and calcium absorption, all contributing to lower bone mass. In these chronically ill patients, osteoclast development increases under the influence of RANK ligand, increasing bone resorption. They may have less osteoblast formation and lower bone formation, he said. “All of these factors converge to create lower bone mass and increased risk of fracture during childhood.” After skeletal maturation, when bone mass begins to decline, adult patients with a history of rheumatic disease during childhood may “reach the fracture threshold earlier than a person with relative health would,” Dr. Burnham said.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) imaging helps rheumatologists assess bone mineral content and areal bone mineral density (BMD). Consider DEXA testing after a patient has taken six to 12 months of glucocorticoids, Dr. Burnham said.

Scores are strongly correlated with the patient’s height, Dr. Burnham said. “Patients with short stature will have a lower area BMD, even if their bones have normal volumetric density.” DEXA Z-scores may be adjusted at least for sex and age, and ideally, for race or other factors that may affect bone density. Z-score calculations that mitigate height bias can now be calculated on the Bone Mineral Density in Childhood Study website (http://www.bmdcspublic.com), he said.

A diagnosis of osteoporosis in a pediatric patient should not be made on the basis of densitometric criteria alone, Dr. Burnham said. A patient should have experienced one or more vertebral compression fractures in the absence of local disease or trauma. Alternatively, a patient should have two or more long bone fractures by age 10, three or more long bone fractures at any age up to 19, or a BMC or a BMD Z-score of less than or equal to -2.

JIA patients face unique risks, he said. “Kids with JIA will all have the same bone risk factors as healthy kids,” including age, gender, nutritional status, intrauterine environment, genetic load, geography and risk-taking behaviors. “But JIA results in impaired cortical and trabecular bone accrual,” possibly due to medications, disease activity and lower muscle mass. They may be at greater risk for falls because of altered balance or muscle weakness, and face higher fracture risks in their arms and legs. If they have one fracture, they have an increased risk of another fracture later on, said Dr. Burnham.

Patients with pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) also face a higher incidence of vertebral fracture risk, he said. In one study of 68 pediatric SLE patients, 56% of the participants had low or low normal spine areal BMD three years after diagnosis.

“Things don’t really get better after diagnosis in pediatric lupus,” he said. Cumulative effects of prednisone may lead to poor lumbar vertebral and trabecular strength. “It also seemed like the biggest decreases in bone mass were in those who developed lupus after puberty. Maybe these patients do not have as much potential to recover from initial losses experienced when disease activity and glucocorticoid therapy were maximal.”

Intervention Strategies

What can rheumatologists do to help young patients increase bone strength? Evidence does not support a strong endorsement for calcium supplementation in this population. Effects may be limited and not long lasting, he said. He recommends adequate calcium in his patients’ diet instead. Rheumatologists may supplement vitamin D, which is deficient in many pediatric lupus patients. The Endocrine Society guidelines recommend between 600 and 1,000 IU per day for an at-risk pediatric patient, with an upper limit of 4,000 IU per day to maintain a 25-hydroxyvitamin D level greater than 30 nanograms per milliliter.

Bisphosphonates, which are not FDA approved for pediatric patients, may help inhibit osteoclast function and bone resorption, but don’t hinder bone formation, Dr. Burnham said. Plan ahead for infusing these patients by checking serum creatinine, calcium and biomarkers of bone metabolism. Ensure that these patients do not need major dental work after infusion begins, and wait at least three weeks after invasive dental work to begin infusions, he said.

Most pediatric rheumatic disease patients will not have a fracture, but it’s important to have a strategy to lower their risk, Dr. Burnham said. Use steroid-sparing agents when possible. Maintain vitamin D levels, ensure dietary calcium intake and recommend physical activity. Patients with rapid weight gain after starting steroids are at greater risk for vertebral compression fractures.

“If you have a patient with bone fragility, you really want to collaborate with your endocrine colleagues,” Dr. Burnham said. Patients who are obese may need nutrition counseling or physical therapy to help them improve and lower their fracture risks.

Susan Bernstein is a freelance medical journalist based in Atlanta.

Second Chance

If you missed this session, it’s not too late. Catch it on SessionSelect.