BOSTON—The uncertainty that surrounds the diagnosis of primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) is “as great as, if not greater than, the diagnostic uncertainty for any other disease encountered in rheumatology,” Leonard H. Calabrese, DO, said at a presentation at the ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting in Boston in November 2014. Diagnostic failure—failure to either recognize the disease or to correctly label a mimic of the condition—is unfortunately common, he said.

Speaking at the session, Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System and Its Mimics, Dr. Calabrese outlined the many reasons why diagnosis is difficult. “It is a rare disease, there are no good animal models, we have no high-efficiency investigation that is noninvasive that can readily make this diagnosis, and we are stimulated by the fact that we do need the diagnostic outcome to be favorable.”

Clinicians seeking a diagnosis may apply the wrong test or rely on vascular imaging when the disease involves a vessel too small for spatial resolution to identify. “More commonly, the errors [of diagnosis] are cognitive,” said Dr. Calabrese, professor of medicine at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine.

A brain biopsy has positive predictive value to rule in the diagnosis of PACNS.

Working criteria, proposed by Drs. Calabrese and Mallek in 1988, outlined the three conditions that must be met for a diagnosis: unexplained neurologic deficits, such as headaches, seizures, multiple strokes, cognitive dysfunction or visual problems, that remain unexplained after a neurologic workup; angiographic features that are compatible with PACNS or a positive biopsy of CNS tissue; and thorough exclusion of all the conditions that could mimic the angiographic finding or could produce a similar pathology, such as infection or malignancy.1 Identifying the mimics is “extraordinarily important” for an accurate diagnosis; some are quite common and some are rare, he said.2

Diagnosis Requires a Team

“There is no specialist or clinician who is an expert in all of the mimics; thus, one of the best practices in approaching CNS vasculitis is to make the diagnosis in a center where there are multiple interested individuals who have multiple skill sets,” he said. Most importantly, diagnosis should never be made based on any single diagnostic activity.

A diagnosis of PACNS should be seriously considered as a possible diagnosis when the patient has chronic meningitis with an aseptic formula for about a six-week period; multiple strokes in multiple vascular territories distributing over time; and focal signs from multiple strokes in different territories, as well as diffuse neurologic dysfunction.

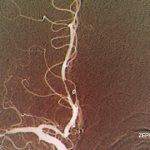

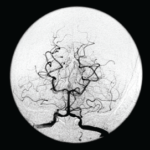

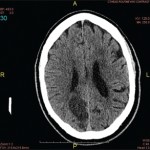

Although there is no uniform approach to a diagnosis, the workup for PACNS is never complete without lumbar puncture, Dr. Calabrese advised. Analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid can help rule out infectious mimics. Magnetic resonance angiography with gadolinium enhancement and diffusion-weighted images should be done when a patient has unexplained ischemia; however, the findings can be nonspecific. There is “no angiographic study of 100% specificity for diagnosis of CNS vasculitis,” he said.

A brain biopsy has positive predictive value to rule in the diagnosis, Dr. Calabrese said. With pathology, “you can be far more confident that this is serious business and requires serious medication.” Although a biopsy is not 100% sensitive and can give a false-negative result, it can help rule out other conditions.

The prognosis is usually favorable if a correct diagnosis is made. Although treatment regimens can vary, Dr. Calabrese said that, for the most part, the most serious forms of PACNS can be treated with cyclophosphamides and glucocorticoids. An antimetabolite can be used for maintenance therapy when a disease is in remission.

Mimics of PACNS

Aneesh Singhal, MD, a neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, presented diagnostic information about reversible angiitis of the central nervous system (RCVS), a syndrome that can mimic PACNS. Unlike PACNS, which typically affects middle-aged men, RCVS is more commonly seen in women age 20–40. The first symptom often recognized in RCVS is a sudden thunderclap headache or several severe headaches that may or may not be accompanied by neurologic deficits. Triggers can include sexual activity, a recent pregnancy and exposure to vasoactive substances, such as marijuana, cocaine, SSRIs and cough or cold suppressants.

The two conditions have other distinguishing differences, Dr. Singhal said. The cerebrospinal fluid analysis should be normal or nearly normal. The MRI can initially be normal, but about 80% of patients will develop abnormalities over time, and some patients have subarachnoid hemorrhage. “This conversion from normal to abnormal does not occur in PACNS,” Dr. Singhal said. Most importantly for diagnosis is the “sausage-on-a-string” appearance on angiogram, the presence of segmental vasoconstriction in multiple cerebral arteries. RCVS is self-limited, with headaches and vasoconstriction resolving over a period of days to weeks.3 Angiographic abnormalities either completely reverse or substantially reverse within about three months.

Treatment is less aggressive for RCVS than for PACNS, Dr. Singhal said, and usually includes glucocorticoids and calcium channel blockers. Long term, the outcome can include chronic headaches and depression.

Three nonatherosclerotic central nervous system vasculopathies can mimic PACNS, according to the third speaker at the session, Cenk Ayata, MD, also a neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. The three commonly present with seizures and migraine with aura and susceptibility to spreading depression. The vascular dysfunction begins before histologic changes and leads to abnormal cerebral blood flow and chronic progressive neurodegeneration.

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is one mimic. CADASIL may start with migraines with aura and can include recurrent strokes and progressive T2 white matter abnormalities on MRI, lacunar infarcts and microbleeds.4

Other mimics are retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophy (RCVL) and HHRATL or hereditary infantile hemiparesis, retinal artery tortuosity and leukoencephalopathy. RCVL is also rare and begins in adulthood with progressive vision loss, stroke-like episodes, dementia, seizures and migraines with and without aura. MRI features of RCVL are similar to CADASIL, and white matter intensities can coalesce to form pseudotumors and small cerebral infarcts. The disease progresses relentlessly, leading to dementia and death.

Onset of HHRATL usually occurs before age 30, and it involves both the retinal and cerebral vessels. White matter intensities are present at about age 30, intracerebral hemorrhage at about the same age and ischemic stroke at about age 35. The condition shares features with PACNS, including progressive focal and diffuse neurologic defects, seizures, headaches and progressive cognitive impairment.

Kathy L. Holliman, MEd, is a medical writer based in Beverly, Mass.

Second Chance

If you missed this session, Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System and Its Mimics, it’s not too late. Catch it on SessionSelect: http://acr.peachnewmedia.com/store/provider/provider09.php.

References

- Calabrese LH, Mallek JA. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Report of 8 new cases, review of the literature, and proposal for diagnostic criteria. Medicine.1988;67:20–39.

- Hajj-Ali RA, Singhal AB, Benseler S, et al. Primary angiitis of the CNS. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(6);561–572.

- Calabrese LH, Dodick DW, Schwedt TJ, Singhal AB. Narrative review: Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(1):34–44.

- Ayata C. CADASIL: Experimental insights from animal models. Stroke. 2010;41(10 suppl):S129–S134.