BOSTON—In a session on the role of macrophages in rheumatic diseases, Macrophages Gone Wild, at the ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting in Boston, November 2014, a panel of experts walked participants through the pathogenesis of and new classification criteria for macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), a severe complication of rheumatic diseases characterized by inflammatory multi-organ failure and hyperferritinemia. Although the complication occurs primarily in the setting of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA), the presence of MAS outside of this setting was also discussed.

Pathogenesis of MAS

Although MAS, in part, got its name from the thought that hemophagocytosis is a primary pathological driver of the disease, Edward M. Behrens, MD, Joseph Lee Hollander Chair in Pediatric Rheumatology, chief, Division of Rheumatology, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, opened the session saying that hemophagocytosis is emerging as less of a driver than previously thought.

As such, he prefers calling this syndrome “cytokine storm syndrome” because of the multiple cytokines being spewed out by the immune systems that lead to systemic inflammatory response caused by the environment, genetic factors or combined factors.

Focusing on genetic-related MAS, he talked about the common pathogenesis of MAS and familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL). Important for the pathogenesis of both MAS and FHL, he said, is a combination of both defects in cytotoxic cell killing, as well as cytokine effects. Key cytokines involved in the pathogenesis include numerous proinflammatory interleukins (ILs), including IL-6, IL-4, IL-1/18 and IL-33, as well as interferon-gamma.

‘We need to recognize what’s been happening in the past, but we need to stop wasting time & dollars on unimportant research.’

He also emphasized that despite the similarities between MAS and FHL, their fundamental pathoetiologies are likely to be different. For example, in FHL, a defect in cytotoxic granule release from CD8+ T cells is a necessary factor, but insufficient for disease development. In MAS, some cases may be due in part to defective cytotoxic granule function, but inflammation-induced cytokines modify or completely supplant this effect.

Although this moves us to a closer understanding of the pathogenesis of MAS, Dr. Behrens emphasized that more work needs to be done to understand how inflammation-induced cytokines may modify the effect of defective cytotoxic granule function on the development of MAS. Potential areas of inquiry include whether hypercytokinemia allow hypomorphic CTL function to reveal itself as MAS and which scenarios don’t require hypomorphic CTL function to turn into MAS.

The clinical relevance of this to the practicing rheumatologist, he said, is that the cause of MAS in each patient is likely related to the underlying rheumatic disease.

“As we learn more about the exact cytokines involved in each case and our diagnostics improve,” he said, “personalized cytokine blockade strategies may become possible to treat MAS.”

Diagnosis of MAS

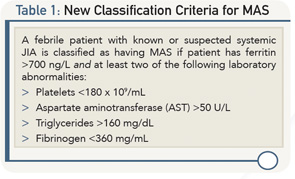

Angelo Ravelli, MD, associate professor of pediatrics, Department of Neuroscience, Rehabilitation, Ophthalmology, Genetics, Maternal and Child Health, University of Genova di Pediatria II—Rheumatologia, Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genova, Italy, presented new classification criteria for MAS in sJIA, developed through a rigorous scientific method based on careful and accurate consensus and statistical analyses and using real patient data.

“The new classification criteria will help standardize the design and conduct of future therapeutic and research studies,” he said, “and contribute to enhancing the knowledge and awareness of the syndrome.”

Table 1 describes the new classification criteria based on more than 80% consensus among the experts who developed the criteria.

He focused the bulk of his talk on recent analyses of the performance of the new classification criteria to diagnose MAS in patients treated with biologics, specifically with tocilizumab and canakinumab.

Although the sensitivity of the new criteria was found to be good in patients treated with these biologic agents, he said that modifications of the criteria may be needed to improve specificity as the new criteria failed to detect MAS in some cases. “A modification of criteria may be needed as the instances of MAS observed in these patients did not display all the classical features of the syndrome, particularly fever, or had some typical laboratory abnormalities blunted, particularly a ferritin peak that was lower than the threshold included in the criteria,” he said.

The suggestions to improve the performance of the classification criteria in patients who develop MAS during anticytokine therapy include eliminating fever as a mandatory criterion and reducing the threshold for ferritin level. However, Dr. Ravelli emphasized that more data are needed to establish whether modification of the criteria is needed to increase their performance in diagnosing MAS in this patient population.

MAS: Independent of sJIA

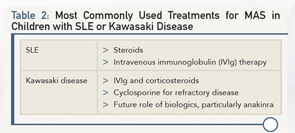

Rayfel Schneider, MBBCh, Department of Pediatrics, The University of Toronto, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada ended the session talking about the occurrence, diagnosis and treatment of MAS in children with rheumatic diseases other than sJIA.

He focused on two pediatric rheumatic diseases other than sJIA in which MAS occurs relatively frequently—systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), in which MAS affects 1–8% of children, and Kawasaki disease, in which MAS affects 1–2% of children—and emphasized the need for an accurate differential diagnosis to ensure that MAS is not underdiagnosed in children.

In making the differential diagnosis, he stressed the need to first exclude infection, malignancy, late presentation of FHL, immunodeficiency syndrome and drug-induced cytopenias and high transaminases.

To make the diagnosis of MAS in children with SLE, he emphasized that MAS often occurs within one week of diagnosis in these children and that the most common triggers are active lupus and flares, as well as infections, a less common trigger. Although the clinical features of MAS in these patients often overlap with SLE, such as active fever, he said that measuring ferritin early in febrile lupus patients can help discriminate MAS from active lupus with fever.

He emphasized that MAS and acute Kawasaki disease share many overlapping clinical features, including fever, lymphadenopathy, rash, hepatomegaly, elevated CRP and transaminases, and low albumin. Similar to patients with SLE, he said that measuring ferritin in children with Kawasaki disease with a persistent fever is important to differentiate MAS from acute Kawasaki disease. Another feature of MAS in these patients is their low platelet counts.

Table 2 lists the most common and emerging treatments for MAS in SLE and Kawasaki disease.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical journalist based in St. Paul, Minn.

Second Chance

If you missed this session, it’s not too late. Catch it on SessionSelect.