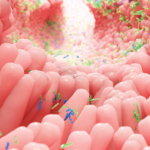

BOSTON—Intestinal bacterial composition and activity play a role in the development of several autoimmune rheumatic diseases. A panel of experts addressed Emerging Perspectives on the Microbiome in the Rheumatic Diseases at the Basic Research Conference prior to the start of the ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting in Boston on Nov. 15, 2014. Gut microbiota may help rheumatologists identify who is most at risk for developing such diseases as ankylosing spondylitis (AS), uveitis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBS) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and facilitate more effective therapies, such as fecal transplants.

Genes & Bugs

Genes, such as HLA-B27, may also play a strong role in a patient’s predisposition to developing certain fecal microbiota that trigger inflammatory diseases. In AS, a disease strongly associated with HLA-B27, increased bowel permeability is common, said James T. Rosenbaum, MD, head of the Division of Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland.

“Dispersion of bacteria from this leaky gut, if it goes to the joints, can lead to inflammation,” said Dr. Rosenbaum. Reactive arthritis is a good example of this phenomenon, but the mechanism is less clear in AS. Researchers recently found that bacteria from tick larvae contributed to the development of Lyme disease, providing an important clue to the bug–disease connection. The bacteria in the tick determine if the spirochete that causes Lyme can proliferate in the tick. “This was a wow to me, a completely unexpected link between the microbiome and one of our rheumatic diseases.”

Rheumatologists may one day be able to prevent inflammatory diseases, such as uveitis or AS, by manipulating patients’ microbiomes despite their DNA, Dr. Rosenbaum said. “Environment is important, and genes are important. Both play a role.”

Triggering Effects

In RA, patients may go through years of preclinical disease when they have evidence of potential triggers, such as anticitrullinated peptide antibody (ACPA). They may develop early synovitis due to environmental exposures, said Jose U. Scher, MD, assistant professor of medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center in New York City.

ACPA and other autoantibodies don’t explain all the changes in RA pathogenesis, and some people who test positive for them have normal synovia, said Dr. Scher. Something else may swoop in to trigger inflammation and activate the disease. “What is the second hit? Can we find an extra-articular source for the pathogenesis of RA?” he asked.

Mucosal bacteria evident in periodontal disease, such as P. gingivalis, is one likely trigger, Dr. Scher said. These flora express peptidyl arginine deiminase (PAD), and antibodies to P. gingivalis are significantly higher in RA patients. “But P. gingivalis’ prevalence correlates with periodontal disease, not arthritis status. Maybe it’s not only P. gingivalis,” said Dr. Scher. “You can have similar microorganisms, but in separate mucosal sites” such as the lung or gut. Prevotella, an intestinal bug that decreases with a high-fat diet, may help predict who will respond better to RA treatments that are metabolized in the gut, like methotrexate, he said.