Prescribing antirheumatic drugs or biologics during pregnancy4

Panchel et al performed a systematic update on consensus papers of antirheumatic and biologic agents and reproduction. Medical subject heading (MESH) and free text was used to search for drug names, rheumatic disease and pregnancy. English language papers from 2006 through 2013 in Embase, Cochrane, PubMed, Lactmed and the UK Teratology Information service were systematically searched. Original pregnancy outcome data were identified in 352 papers. Drugs identified in these papers included abatacept, adalimumab, azathioprine, certolizumab, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, etanercept, hydroxychloroquine, infliximab, LEF, MTX, mycophenolate mofetil, prednisolone, sulfasalazine and anti-TNFα combinations (infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, certolizumab). The evidence from this review supports the compatibility of using azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine and steroids in pregnancy. There is increasing evidence of compatibility, mostly at conception or during the first trimester, found from pregnancies exposed to anti-TNFα agents, that does not show an appreciable increase in the number of spontaneous miscarriages and congenital malformations. The authors note that further registry data are required for biologic agents before they can safely be recommended throughout pregnancy.

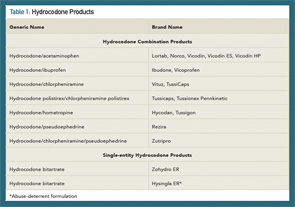

Hydrocodone Combination Products

Rescheduling to control misuse & abuse

Hydrocodone combination products (HCPs) are among the most commonly prescribed opioid analgesics in the U.S., with 137 million prescriptions dispensed in 2013.5 Widespread use of hydrocodone has contributed significantly to opioid misuse and abuse. Since the Controlled Substances Act was passed in 1970, hydrocodone-only products have been Schedule II (C-II) controlled substances; whereas, HCPs have been Schedule III (C-III) controlled substances. Effective Oct. 6, 2014, a final rule by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) moved HCPs from C-III to C-II, placing more restrictions on their use.6

Key changes to the rescheduling of HCPs:

- Prescriptions for HCPs that were issued on or after Oct. 6, 2014, must comply with requirements for Schedule II prescriptions;

- Refills are not allowed on new HCP prescriptions;

- Prescriptions for HCPs may be written on a hard copy, original prescription or received by electronic transmission, where allowed. Receipt by fax will not be allowed;

- Pharmacies must use a DEA Form 222 to purchase HCPs from a distributor. Purchasing and stocking HCPs will require additional recordkeeping and security requirements;

- Prescriptions for HCPs that are issued before Oct. 6, 2014, that have authorized refills may be dispensed in accordance with DEA rules for refilling, partial filling, transferring and central filling Schedule III-V controlled substances until April 8, 2015. However, state law, insurance limitations, and some pharmacy quality and safety operations and processes may not allow for these prescriptions to be refilled. Prescribers should be prepared to provide a new hard copy or a new electronic prescription for patients after Oct. 6, 2014, rather than have patients use what would have been existing refills;

- Pharmacies may continue to dispense HCPs in commercial containers labeled as Schedule III controlled substances, rather than placing the medication in a prescription vial. However, the DEA requires all other commercial containers of HCPs to be labeled as Schedule II controlled substances (this applies to manufacturers and distributors);

- The DEA permits prescribers to issue multiple prescriptions authorizing a patient to receive a total of up to a 90-day supply of HCPs; and

- Phone-in refills for HCPs are no longer allowed except for emergency situations. In these emergency cases, a small supply of up to five days may be authorized for filling and dispensing until a new “hard copy” prescription can be provided to the pharmacy for the patient. The new prescription must be provided to the pharmacy within seven days of the phoned-in emergency prescription. The face of the prescription must state, “Authorization for Emergency Dispensing.”

In 2012, the FDA approved a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) for highly potent opioids, such as extended-release (ER) and long-acting (LA) medications.7,8 A major goal of opioid REMS programs was to reduce harm from prescription opioid misuse and abuse while continuing to provide access to these medications for patients’ pain management. Another strategy to achieve the goal of reducing harm from opioids was the development of abuse-deterrent formulations. Abuse-deterrent formulations are designed to reduce people’s ability to extract the active opioid ingredient from the dosage form. Individuals can try to do this by chewing the formulations and/or smashing them into a powder so they snort or inject the opioid. In late November (2014), the FDA approved hydrocodone bitartrate (Hysingla ER) as an “abuse-deterrent” tablet that cannot be easily crushed or chewed.9 The product forms a thick gel when crushed, making it difficult to inject. At the time of this writing, Table 1 lists the currently available HCPs and single-entity hydrocodone products.