A large, deep, painful ulceration is present on the lateral margin of the tongue in this patient with Behçet’s syndrome.

ACR IMAGE BANK

SAN FRANCISCO—Behçet’s disease is a vasculitis that can be hard to pin down, with a wide variety of manifestations, many of which overlap with other auto-inflammatory conditions, an expert said at a clinical review course at the 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting.

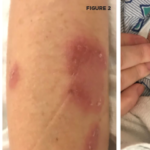

The most common feature is oral ulcers, which are expected to be seen at some point in the course of the disease, but patients can present with skin lesions, arthritis, amyloidosis, uveitis and joint problems, said Seza Ozen, MD, professor of pediatrics at Hacettepe University in Turkey.

The issues that arise from the disease can often seem unrelated. Complicating matters, it’s characterized by flares and remissions that can simply come and go on their own.

“The diagnosis is sometimes quite challenging,” Dr. Ozen said.

In fact, she said, therapies have been little studied—with very few evidence-based treatments—in part because of the disease variations that are seen, she said.

“Some patients tend to present with some skin lesions only,” Dr. Ozen said, while “some tend to present with severe eye disease as the prominent feature, and some can present with more vascular features.”

Prevalence

Prevalence varies widely, as well. In Turkey and Japan, Behçet’s occurs in more than 1 per 1,000 people. Mayo Clinic estimates prevalence in the U.S.-based population to be 5.2 per 100,000, Dr. Ozen said.

And there appears to be a genetic link to the disease. A study out of France found the North African and Asian subpopulations there had a prevalence of 34.6 and 17.5 per 100,000—about the same as the prevalence found in the native countries of those ethnicities, suggesting genetics is in play more than environmental factors, Dr. Ozen said.

Genetics

Two genome-wide association studies in 2010 found that susceptibility links between Behçet’s and the IL10 and IL23R genes. In one of the studies, the presence of the HLA B51 gene, known to be a risk factor for the disease, seemed to depend on the presence of the gene ERAP1.1,2

Dr. Ozen said it’s theorized that ERAP1, which provides instructions for making proteins, may cause problems with protein folding, including the misfolding of HLA B51, leading to activation of IL23 and IL17, which then join together in an inflammatory response.

She noted similarities to ankylosing spondylitis: uveitis, arthritis and gastrointestinal issues, and the association with an HLA and IL17.

Further research in 2013 pointed to the role of two more genes—the Mediterranean familial fever gene, MEFV, and TLR4—suggesting that innate immune and bacterial sensing mechanisms are at work in Behçet’s.3

Diagnostic Criteria for Children

Dr. Ozen drew special attention to the challenge of diagnosing children. According to criteria written in 1990, diagnosis of Behçet’s in children requires oral ulcers along with two of these four criteria: uveitis or retinal vasculitis, genital ulcers, pustules and/or erythema nodosum and pathergy.

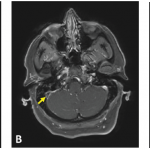

Case study: A 12-year-old boy, for example, presented to her with jugular venous thrombosis, with a history of a cardiac pacemaker, recurrent ulcers for two or three years, non-specific arthralgia and a maternal history of Behçet’s. Ophthalmology and pathergy tests were negative.

Finally, a stool system was positive for blood, and a colonoscopy found ulcers typical of Behçet’s.

“We had to treat it as such—but when you look back, he presented to us with only one criteria—the oral ulcers only,” she said.

She suggests a wider set of new criteria—the details of which she is not ready to widely disseminate—which she hopes are helpful with diagnosis and management, “so that we can diagnose them earlier and treat them earlier, because, really, the diagnosis [may] be challenging sometimes.”

Treatment

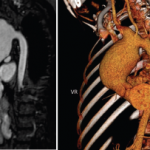

Treatment for Behçet’s is not well studied, but there are a few standards, Dr. Ozen said. She cautioned that patients with pulmonary aneurysms should not be given anticoagulants because of “a very significant risk of rupture.” But that is the only scenario in which anti-coagulants should not be used, she said.

A collaboration of three centers in France, Italy and Turkey studied thrombosis in pediatric Behçet’s and found that there was no consensus on whether to give anticoagulants in these patients, but Dr. Ozen said she does so “to be on the safe side.”4

The only evidence-established treatment is the immunosuppressant azathioprine for inflammatory eye disease, Dr. Ozen said, although she cautioned that azathioprine alone may not be enough.

Patients with pulmonary aneurysms should not be given anti-coagulants because of ‘a very significant risk of rupture.’ —Dr. Ozen

There is no evidence-based treatment for gastrointestinal involvement, but sulfasalazine, steroids, azathioprine and anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) medications are recommended. First-line treatment for oral and genital ulcers is topical, she said. The anti-gout agent, colchicine, is recommended for nodular lesions.

There are no firm data for central nervous system involvement and vascular disease, she said, but steroids, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, interferon and anti-TNFs have been recommended, “depending on the extent of the involvement.”

For venous thrombosis in Behçet’s, “certain experts give (anti-coagulants), and certain experts don’t. And we have never seen an emboli due to thrombosis in Behçet’s disease.”

A colchicine trial has shown improvement in ulcers and some skin lesions, especially pseudofolliculitis and erythema nodosum, Dr. Ozen said.5

But a lack of hard data is a real problem in handling this multi-faceted disease, she said.

“We lack activity criteria and evidence-based treatment guidelines,” she said, “so that is something we want to pursue.”

Thomas R. Collins is a medical writer based in Florida.

Second Chance

If you missed this session, it’s not too late. Catch it on SessionSelect.

References

- Mizuki N, Meguro A, Ota M, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify IL23R-IL12RB2 and IL10 as Behçet’s disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010 Aug;42(8):703–706.

- Remmers EF, Cosan F, Kirino Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the MHC class I, IL10, and IL23R-IL12RB2 regions associated with Behçet’s disease. Nat Genet. 2010 Aug;42(8):698–702.

- Kirino Y, Zhou Q, Ishigatsubo Y, et al. Targeted resequencing implicates the familial Mediterranean fever gene MEFV and the toll-like receptor 4 gene TLR4 in Behçet disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 May 14;110(20):8134–8139.

- Krupa B, Cimaz R, Ozen S, et al. Pediatric Behcet’s disease and thromboses. J Rheumatol. 2011 Feb;38(2):387–390.

- Davatchi F, Sadeghi Abdollahi B, Tehrani Banihashemi A, et al. Colchicine versus placebo in Behçet’s disease: Randomized, double-blind, controlled crossover trial. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19(5):542–549.