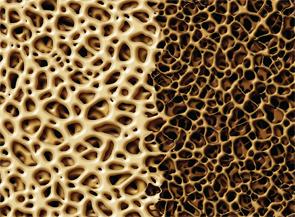

Bone with osteoporosis: Strong, healthy, normal spongy tissue (left) contrasted with unhealthy, porous weak structure due to aging or illness.

Lightspring/shutterstock.com

SAN FRANCISCO—The discovery of a promising new target for the treatment of osteoporosis has a beginning to the story that, when it comes to scientific breakthroughs, rings familiar: It started with a disappointment.

Researchers in the lab of Laurie H. Glimcher, MD, the Stephen and Suzanne Weiss Dean of Weill Cornell Medical College—were in search of a transcription factor that controls differentiation of type-1 T-lymphocytes, and turned to Schnurri-3, part of a small family of very large proteins that has been highly conserved through evolution. Schnurri-3, they found, didn’t do that.

But Dr. Glimcher figured that it had to do something—it had to have some phenotype in the immune system, given that so many effects on immune cells had been seen ex vivo. Then she learned that her lab had not yet looked at bone marrow.

When they looked at X-rays of mice in whom Schnurri-3 had been knocked out, they were startled: “The animals had massively increased bone mass,” Dr. Glimcher recalled, in her Oscar S. Gluck, MD, Memorial Lecture, given at the 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting.

As they continued to examine the gene and its mechanisms, they realized that it might be the key to a new treatment approach in osteoporosis, which affects more than 200 million people worldwide, with one in three women and one in five men suffering an osteoporosis-related fracture in their lifetime.

Osteoporosis is the world’s most common disease—more prevalent than cancer or heart disease, Dr. Glimcher noted. But therapies have been hampered because those that promote bone growth also, eventually, promote bone decay and vice versa.

New therapies are under investigation that would buck this trend, such as the cathepsin K-inhibitor odanacatib and the sclerostin antibody CDP7851.

In a particularly exciting discovery, researchers found that knocking out Schnurri-3 resulted in a kind of decoupling of bone resorption & formation.

Dr. Glimcher said that therapies targeting Schnurri-3 also hold much promise. Once the attention of her lab turned to Schnurri-3’s role in bone growth, they looked into how loss of the gene affects age-associated bone loss. In Schnurri-3 knockout mice they found that bone continued to accumulate from baseline at six weeks through 18 months.1

Moreover, Dr. Glimcher said, “there is no apparent secondary pathology that one needs to worry about. The bone that’s formed by biophysical analysis is lamellar bone. It has increased strength.” There was also no ectopic mineralization and no instance of osteosarcomas seen—and they’ve been observing the mice for more than 12 years.