Can a heart involved with amyloid tolerate the immunologic chaos that might occur when you’re directing antibody attack on a major organ?

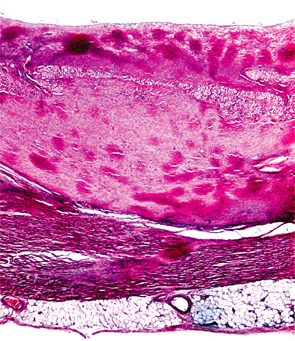

Image Credit: Biophoto Associates/Science Source

SAN FRANCISCO—Treatment for transthyretin-related amyloidosis (ATTR) is generating more interest from academic researchers and the pharmaceutical industry, with encouraging early results using a multi-pronged therapeutic approach, a researcher said at a review course held before the 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting.

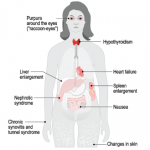

Amyloidoses are a rare and potentially deadly family of diseases in which misfolded protein builds up in organs, with symptoms that often make themselves known only after the disease has progressed significantly. It comes in the form of primary amyloidosis, stemming from abnormal plasma cells; secondary amyloidosis, derived from the inflammatory protein serum amyloid A; and familial forms.

Only about 3,000–4,000 cases of primary amyloidosis, the most common form, are seen in the U.S. each year, according to the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

ATTR, the most common type of hereditary amyloidosis, is even more rare, with only about 10,000 people affected worldwide. The disease involves protein deposits to the nerves, GI tract, heart and eyes, with a median survival of 5–15 years.

“TTR represents 10 to 20% of amyloid seen in the U.S. and Europe,” said presenter John Berk, MD, clinical director of the Amyloid Center at Boston University School of Medicine. “Impressively, over the past 10 years, industry has [spent], and will spend, more than $600 million on clinical trials for drug development in ATTR. And that’s the result of their investigational products being preferentially delivered to the liver where the amyloidogenic TTR protein is generated.”

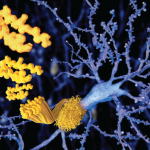

The TTR protein normally transports thyroid hormone and vitamin A, but people with mutations in the TTR gene produce variants of the protein throughout their lives, causing formation of amyloid fibrils.

It’s been about two years since Dr. Berk led a trial on an unlikely candidate for ATTR treatment: the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug diflunisal.

Diflunisal in Studies

Diflunisal has been found to stabilize transthyretin tetramers and prevent amyloid fibril formation in vitro. In the trial, researchers randomized 130 patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy, featuring progressive peripheral nerve deficits and disability.1 Half were assigned to get 250 mg of diflunisal twice a day for two years, and half were assigned to placebo.

There was a high level of dropout in the study, mainly because of disease progression and ready access to the active drug outside the study, according to Dr. Berk.

But the results were dramatic. Disease progression was measured by the Neurologic Impairment Score plus 7 nerve tests (NIS + 7), a 270-point scale, a comprehensive instrument combining clinical assessment, EMG measures, and computer-directed sensory testing. The score increased by 25 in the placebo group vs. only 8.7 points in the diflunisal group (p<.001). This makes a big difference functionally, according to Dr. Berk.

“What does that mean? It’s the strength to get out of a chair,” he said. “If you don’t think that’s significant, when you have neuropathy and can’t get out of a chair or off the toilet, you’ll feel differently.”

Overall, there is good cause for optimism in amyloidosis treatment.

TTR stabilization, he said, “definitely works.”

“Diflunisal inhibits neurologic disease dramatically,” he said. “Almost a third of the people taking diflunisal for two years had no change in their NIS score, no neurologic progression. It preserves or improves quality of life. It’s effective across mutations, gender, severity of disease and it gives new life to an obsolete drug.”

Tamafadis

Another agent, tamafadis, studied just before the diflunisal, also stabilizes the tetramer. It doesn’t come with the toxicity concerns of an anti-inflammatory, but is more costly. In a trial, it showed an effect but didn’t meet its primary endpoint. It has been approved in Europe, though not in the U.S.

Other Therapies

According to Dr. Berk, despite the successes, most patients on TTR stabilizing agents—about 70%—still progress slowly. So there’s a need for better therapy. Two companies—Alnylam and Ionis—have been working on TTR gene-silencing therapies. Both drugs have been found to suppress TTR protein production, diminishing circulating TTR dramatically.

In a phase II trial presented in November at the European Congress on Hereditary ATTR, in which Dr. Berk was an investigator, Alnylam’s agent was found to bring about sustained, 80% suppression of TTR levels.2 A randomized, Phase 3 trial to assess effects on neurologic deficits is now underway.

The latest therapeutic efforts in amyloidosis involve deploying antibodies to knock out a building block of amyloid in the hope that this will lead to the elimination of the deposits. The approach, described recently in the New England Journal of Medicine, involves treating patients with systemic amyloidosis with an agent known to clear serum amyloid P from the plasma, then using antibodies to target SAP in the deposits themselves.3 So far, Phase 1 results show that the approach can safely clear amyloid from the liver and some other tissues.

But the effects in other organs are not yet known.

“It’s a real question as to whether a heart involved with amyloid can tolerate immunologic chaos that might occur when you’re directing antibody attack on a major organ,” Dr. Berk said.

Overall, there is good cause for optimism in amyloidosis treatment, he said: “We haven’t identified all the therapeutic answers yet, but the future truly is bright.”

Thomas R. Collins is a medical writer based in Florida.

Second Chance

If you missed this session, it’s not too late. Catch it on SessionSelect.

References

- Berk JL, Suhr OB, Obici L, et al. Repurposing diflunisal for familial amyloid polyneuropathy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013 Dec 25;310(24):2658–2667.

- Suhr OB, Coelho T, Buades J, et al. Phase 2 Open-Label Extension Study of Patisiran An Investigational RNAi Therapeutic for the Treatment of Familial Amyloidotic Polyneuropathy. Presented Nov. 3, 2015 at the First European Congress on Hereditary ATTR Amyloidosis. Paris, France.

- Richards DB, Cookson LM, Berges AC, et al. Therapeutic clearance of amyloid by antibodies to serum amyloid P component. N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 17;373(12):1106–1114.