designer491/shutterstock.com

SAN FRANCISCO—The Kveim-Siltzbach skin test for a diagnosis of sarcoidosis was developed in 1941, then popularized in 1961. Since then, the knowledge base about the disease has not expanded much, said Kristin Highland, MD, who has dual appointments at Cleveland Clinic’s Respiratory Institute and Orthopedics and Rheumatology Institute.

“We don’t know a whole lot more since that time,” Dr. Highland said in a talk at the 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting. “We don’t know, really, the etiology or a detailed pathogenesis or standard treatment or a good method to assess therapy or a good method for follow-up.” This is despite thousands of published articles on sarcoidosis.

But enough is known about the disorder to give clinicians guidance on how to spot and how to treat the disease—if treatment is necessary, which it often is not.

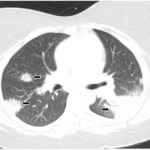

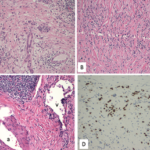

Sarcoidosis—inflammation, thought to be brought about by airborne particles, that affects organs throughout the body, but mostly the lungs—is diagnosed when “clinicoradiological findings are supported by histological evidence of non-caseating epithelioid cell granulomas,” according to the American Thoracic Society. But “granulomas of known causes and local sarcoid reactions must be excluded.”

“So this is a diagnosis of exclusion,” Dr. Highland said.

The mortality, which is thought to have a genetic basis, is rising in the U.S., and so is the number of hospitalizations of people with sarcoidosis, although hospitalizations specifically due to sarcoidosis have plateaued, she said.1

Agents thought to bring about sarcoidosis include Myobacterium tuberculosis, fungi, viruses, beryllium, pine pollen, pesticides and agents associated with firefighting.

Dr. Highland stressed that if you’re thinking about a diagnosis of sarcoidosis in the lung, infections need to be ruled out and “a very careful review of systems” has to be undertaken to rule out etiologies more likely linked with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. In the case of other organs, lymphoma needs to be considered. Sometimes, therapy, including methotrexate, can bring about a granulomatous-type reaction that can be confused with sarcoidosis, she said.

A Tricky Diagnosis

The diagnosis, therefore, can be tricky. A review of new sarcoidosis referrals at her former center over a seven-month period found that one in six of the patients did not actually have sarcoidosis, Dr. Highland said.

Clues that should cause clinicians to suspect sarcoidosis include African-American race, female gender, symmetric bilateral hilar adenopathy and an asymptomatic presentation.

Another element making sarcoidosis a difficult-to-manage disease is that it “can affect virtually any organ that it wants to,” Dr. Highland said, although the lungs are involved in about 95% of cases. Deaths from sarcoidosis are most often due to lung, heart or central nervous system involvement.