designer491/shutterstock.com

SAN FRANCISCO—The Kveim-Siltzbach skin test for a diagnosis of sarcoidosis was developed in 1941, then popularized in 1961. Since then, the knowledge base about the disease has not expanded much, said Kristin Highland, MD, who has dual appointments at Cleveland Clinic’s Respiratory Institute and Orthopedics and Rheumatology Institute.

“We don’t know a whole lot more since that time,” Dr. Highland said in a talk at the 2015 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting. “We don’t know, really, the etiology or a detailed pathogenesis or standard treatment or a good method to assess therapy or a good method for follow-up.” This is despite thousands of published articles on sarcoidosis.

But enough is known about the disorder to give clinicians guidance on how to spot and how to treat the disease—if treatment is necessary, which it often is not.

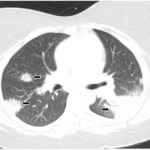

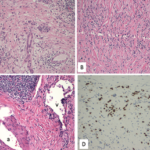

Sarcoidosis—inflammation, thought to be brought about by airborne particles, that affects organs throughout the body, but mostly the lungs—is diagnosed when “clinicoradiological findings are supported by histological evidence of non-caseating epithelioid cell granulomas,” according to the American Thoracic Society. But “granulomas of known causes and local sarcoid reactions must be excluded.”

“So this is a diagnosis of exclusion,” Dr. Highland said.

The mortality, which is thought to have a genetic basis, is rising in the U.S., and so is the number of hospitalizations of people with sarcoidosis, although hospitalizations specifically due to sarcoidosis have plateaued, she said.1

Agents thought to bring about sarcoidosis include Myobacterium tuberculosis, fungi, viruses, beryllium, pine pollen, pesticides and agents associated with firefighting.

Dr. Highland stressed that if you’re thinking about a diagnosis of sarcoidosis in the lung, infections need to be ruled out and “a very careful review of systems” has to be undertaken to rule out etiologies more likely linked with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. In the case of other organs, lymphoma needs to be considered. Sometimes, therapy, including methotrexate, can bring about a granulomatous-type reaction that can be confused with sarcoidosis, she said.

A Tricky Diagnosis

The diagnosis, therefore, can be tricky. A review of new sarcoidosis referrals at her former center over a seven-month period found that one in six of the patients did not actually have sarcoidosis, Dr. Highland said.

Clues that should cause clinicians to suspect sarcoidosis include African-American race, female gender, symmetric bilateral hilar adenopathy and an asymptomatic presentation.

Another element making sarcoidosis a difficult-to-manage disease is that it “can affect virtually any organ that it wants to,” Dr. Highland said, although the lungs are involved in about 95% of cases. Deaths from sarcoidosis are most often due to lung, heart or central nervous system involvement.

The baseline evaluation in suspected sarcoidosis cases should include a complete history with an emphasis on occupational and environmental exposure, a physical exam, blood tests, chest X-ray, spirometry test, electrocardiogram, an ophthalmologic exam and a purified protein derivative test to screen for tuberculosis.

Pulmonary manifestations can include dyspnea, a cough that’s usually dry, chest pain, wheezing or no symptoms at all. Asthmatic symptoms are common, Dr. Highland said.

Sarcoidosis skin involvement can include specific manifestations like maculopapules, subcutaneous nodules, infiltrations of scars and lupus pernio, or non-specific conditions such as erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme and rash, she said.

Manifestations of neurosarcoidosis include CNS masses, aseptic meningitis, encephalopathy, seizures, peripheral neuropathy and myopathy.

Cardiac sarcoidosis is a serious form because it “can result in sudden death,” Dr. Highland said. It can take the form of conduction disturbances, ventricular arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, valvular dysfunction, pericarditis and other issues. Survival with cardiac sarcoidosis largely depends on whether a patient has a preserved ejection fraction, she said.

Treatment

It’s important to remember, she said, that “not every patient needs to be treated.”

“If they’re doing fine [and] they’re relatively asymptomatic, remission is likely with only a small minority having relapses,” Dr. Highland said. “Whereas if they have organ dysfunction, they’re more likely to have evidence of persistence or relapses.” And two-thirds of patients have a spontaneous remission “whether we do anything or not.”

Clues that should cause clinicians to suspect sarcoidosis include African-American race, female gender, symmetric bilateral hilar adenopathy & an asymptomatic presentation.

Corticosteroids are the first-line treatment choice, followed by immune modulators among those with an inadequate response.2 Infliximab is the only medication that has been proved effective in a double-blind randomized controlled trial, Dr. Highland noted.3

Treatment should probably be started right away, she said, in cases of an active neuromuscular or cardiac disease, hepatosplenic involvement with symptoms, significant hypercalcemia, ophthalmic disease that doesn’t respond to topical steroids and disfiguring dermatologic disease, such as lupus pernio.

Thomas R. Collins is a medical writer based in Florida.

Second Chance

If you missed this session, it’s not too late. Catch it on SessionSelect.

References

- Rossman MD, Thompson B, Frederick M, et al. HLA-DRB1*1101: A significant risk factor for sarcoidosis in blacks and whites. Am J Hum Genet. 2003 Oct;73(4):720–735.

- Gibson GJ, Prescott RJ, Muers MF, et al. British Thoracic Society Sarcoidosis study: Effects of long term corticosteroid treatment. Thorax. 1996 Mar;51(3):238–247.

- Baughman RP, Costabel U, du Bois RM. Treatment of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2008 Sep;29(3):533–548.