Clinical Case

RB, a 66-year-old man, presented to the hospital in July 2011 with left-sided visual loss (OS), headache, hematuria, and symptoms of a chronic sinusitis. He was in his usual state of health until the summer of 2009, when he began to develop frequent sinus infections manifesting with headache, sinus pain, and nasal congestion without epistaxis or crusting. He was treated with multiple courses of antibiotics, each time with improvement of his symptoms.

In February 2011, he began to have headaches that did not resolve with antibiotic treatment. Shortly thereafter, he developed urinary frequency, urgency, weak stream, and intermittent gross hematuria. He was seen by a urologist and the diagnosis of benign prostatic hypertrophy was made on the basis of a digital rectal exam and a normal prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level. Several weeks later, he developed incontinence and was diagnosed as having a neurogenic bladder requiring self-catheterization. In March 2011, he was hospitalized at another hospital for severe headache. At that time, computed tomography (CT) imaging of the brain revealed chronic sinusitis with no other abnormalities. A chest X-ray was unremarkable. A sinus biopsy showed nonspecific inflammatory changes and the antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) testing was normal. He was discharged home to complete a course of antibiotics for the treatment of his sinusitis.

Send us Your Case Suggestion

Have you managed a patient with an unusual rheumatologic problem that you would want to present to a larger audience? Consider submitting your case to The Rheumatologist.

We are looking for interesting cases that are well written and provide useful teaching points to the reader. Send an outline of your case presentation to Simon Helfgott, MD, at [email protected], or visit www.The-Rheumatologist.org for more information.

In April 2011, he developed a urinary tract infection due to Candida albicans. His course was complicated by candidemia, which was treated with a two-week course of fluconazole.

Over the following month his headache persisted and he developed eye pain, diplopia, and numbness in the V1–V2 distribution of the trigeminal nerve. He was admitted to another hospital, where a CT of the brain showed a destructive sinus process that was invading into the left orbital wall. He underwent a second sinus biopsy, which demonstrated acute and chronic inflammation without evidence for vasculitis, granulomas or invasive fungal disease. Sinus tissue cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus and he was started on doxycycline. After one month of therapy he did not note any improvement in his symptoms and began to notice new visual loss in his left eye. He was referred to our hospital.

On admission, he complained of double vision that progressed to complete visual loss OS during the week prior to admission. His sinus symptoms persisted and he reported frequent nasal discharge that was green and occasionally brown and bloody. He noted a persistent feeling of numbness on his left cheek and forehead. He reported severe fatigue and an 80-pound weight loss over the prior four months. He continued to have lower urinary tract symptoms with intermittent gross hematuria, which he attributed to self-catheterization. He denied fevers, chills, night sweats, hearing loss, respiratory symptoms, abdominal pain, changes in bowel habits, joint pain, numbness, or weakness of his extremities.

His medications included doxycycline, glyburide, timolol, and travoprost eye drops. He had no allergies or family history of rheumatologic disease. He previously worked as a realtor but had to stop working due to his illness. He lived alone without pets. He had traveled to Bermuda during the previous year and denied known exposure to tuberculosis. He smoked two packs per day for 30 years but quit 12 years prior.

On exam, he appeared chronically ill with temporal wasting bilaterally. He had proptosis of the left eye with left nasal bridge and periorbital edema. He was unable to open the left eye on his own. With assistance, it was noted that his left eye was deviated to the left and he had limited ocular movement in all directions. The sclera were clear. Nasal examination demonstrated mild congestion anteriorly without perforation. Neurological exam revealed loss of sensation in the V1–V2 distribution of the trigeminal nerve. His lungs were clear. There was no evidence of synovitis or skin lesions.

Laboratory workup revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 11,900 (ref 4.8–10.8 x 1000) with neutrophil predominance, creatinine 0.87mg/dL (ref 0.8–1.3 mg/dL), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 92 mm/hr (ref <11 mm/hr), and C-reactive protein (CRP) 91.1mg/L (ref <8 mg/L). Antinuclear antibody, ANCA, human immunodeficiency virus, angiotensin converting enzyme, purine protein derivative (PPD), 1-3 B-glucan, and galacatomannan testing was negative. Urinalysis revealed greater than 100 red blood cells (RBCs) and greater than 100 white blood cells (WBCs) per high power field. Review of the sediment did not demonstrate any dysmorphic RBCs or RBC casts. Urine cultures grew >100,000 CFU/ml of C. albicans. Blood cultures were negative.

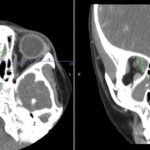

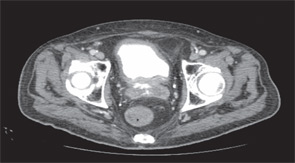

Imaging of the orbit demonstrated destruction involving the left lateral nasal wall, floor of the orbit, middle turbinate, roof of the nasopharynx, and the sphenoid sinus with abnormal soft tissue density along the left medial orbital wall and orbital floor with extension through several skull base foramina (see Figure 1). A chest CT demonstrated a right-middle lobe cavitary lesion measuring 2 cm by 2 cm with a small satellite lesion (see Figure 2). An abdominal CT demonstrated a locally invasive process involving the prostate gland, bladder, and seminal vesicles, as well as a 2.7cm by 2.1 cm renal mass (see Figure 3).

RB underwent an open left nasosinus biopsy using a canthal approach. During the procedure, a large amount of necrotic material was encountered that extended into the bone with destruction of the left lamina papyracea. His sinus cultures grew moderate coagulase-negative staphylococcus and rare Clostridium birefrementas, which were felt to be colonizers. Sinus biopsies demonstrated chronic inflammation and several giant cells without granulomas or vasculitis.

Subsequently, RB underwent cystoscopy, which demonstrated a necrotic urethra with the process affecting the bladder base. Biopsies of the urethra and bladder revealed acute and chronic inflammation with necrosis without evidence of malignancy or infection.

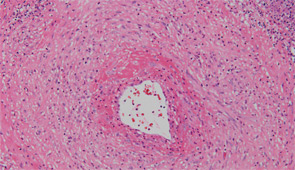

After sputum samples were negative for acid-fast bacilli on three consecutive days he underwent video-assisted thoracoscopic lung biopsy of the area encompassing the cavitary lung lesion. During the procedure the lesion was found to contain pus. Cultures of the abscess were negative. Microscopic examination of the lung specimen demonstrated granulomatous vasculitis without acid-fast bacilli or fungal elements consistent with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) (Wegener’s) (see Figure 4). Repeat head imaging demonstrated air-fluid collections underlying the left frontal sinus and in the middle cranial fossa inferior to the foramen rotundum measuring 1.3 cm by 0.5 cm. The infectious disease consultants felt that these were likely postoperative changes; however, broad spectrum antibiotics were recommended for two weeks.

The patient was started on a two-day course of intravenous glucocorticoids followed by prednisone 60 mg daily and received two infusions of rituximab 1,000 mg given two weeks apart. His headaches and fatigue improved and his weight loss stabilized. Three weeks after hospital discharge he was hospitalized because of an episode of Clostridium difficile colitis that resolved with metronidazole treatment. He improved slowly but continued to have drainage from the canthal incision. He was followed by the ear, nose, and throat service, who felt there was no clear evidence of infection. Three months after hospital discharge, he underwent routine follow-up head imaging that revealed a markedly enlarged intracranial-fluid collection. He was taken emergently to surgery where a 3 cm by 3 cm brain abscess was evacuated. Cultures grew Aspergillus fumigatus. Despite treatment with liposomal amphotericin, voriconazole, and multiple debridements, his condition continued to deteriorate and, after a four-week hospital course, his family opted for comfort measures only.

Discussion

This case illustrates several important points regarding the diagnosis and treatment of GPA. For RB, the diagnosis of GPA was delayed by several months because of repeated negative ANCA testing and having several superimposed infections, which can mimic some of the upper airway disease that can be seen in patients with GPA.

ANCA testing, when performed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunoflorescence testing, is up to 96% sensitive in systemic disease, but only up to 83% sensitive in localized disease.1,2 While RB had systemic disease, including lung and genitourinary (GU) involvement, he was in the small minority of patients that is ANCA negative despite repeated testing.

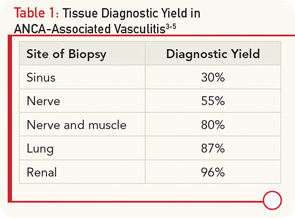

In the absence of ANCA positivity, definitive confirmation of AAV requires tissue diagnosis. The site of biopsy is an important determinant in the utility of the tissue specimen (see Table 1). Our patient underwent several sinus biopsies that yielded nonspecific results. This is not surprising, because a retrospective analysis of 158 patients with confirmed GPA demonstrated that nasal and sinus biopsies demonstrate vasculitis in less than 30% of patients, and even granulomas are seen in less than 60% of cases.3 In contrast, lung biopsy specimens from the same series demonstrated vasculitis in 87% and, indeed, the diagnosis in our case was confirmed with a lung biopsy. If there is evidence of renal involvement, a kidney biopsy may yield the diagnosis in over 95% of cases.4 An important consideration in interpreting renal biopsy results is whether the biopsy contains sufficient glomeruli, because the same series demonstrated that up to 40% of glomeruli from patients with GPA appeared normal on histology. The absence of an active urinary sediment suggested that our patient did not have significant glomerular involvement. Similarly, nerve biopsies have a relatively high diagnostic yield. A series of 83 patients with vasculitic neuropathy demonstrated that a nerve biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of vasculitis in 55% of patients, while a combined nerve and muscle biopsy increased the yield to 80% of patients.5

RB’s presentation, while in many ways classic for GPA, also had some atypical features. Specifically, genitourinary involvement is an uncommon presenting symptom in AAV, with only case reports describing prostatic, urethral, and penile involvement.6,7 However, an autopsy series done over 50 years ago demonstrated prostatic involvement in 7% of patients with GPA.8 Despite widespread systemic disease, he lacked any significant musculoskeletal symptoms, fevers, or rash. It has been reported that fewer than 70% of patients have prominent musculoskeletal complaints and less than a quarter of patients have skin disease at presentation.1,5

As demonstrated by this case, we must always be mindful of infection. While the vast majority of patients with AAV achieve remission following induction therapy with glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide or rituximab, longer follow up suggests that the disease carries a 10% to 20% mortality with close to 25% of deaths attributable, at least in part, to infection.5,9

Take-Home Points

- ANCA testing is up to 96% sensitive in systemic AAV, but decreases in sensitivity with localized disease.

- Lung and renal biopsies, followed by combined nerve/muscle biopsy, have the highest diagnostic yield in systemic vasculitis, while sinus biopsies are often nondiagnostic.

- GPA should be considered in patients with atypical presentations of genitourinary disease.

Dr. Miloslavsky is a rheumatology fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

- Nölle B, Specks U, Lüdemann J, et al. Anticytoplasmic autoantibodies: Their immunodiagnostic value in Wegener granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:28-40

- Finkielman JD, Lee AS, Hummel AM, et al. ANCA are detectable in nearly all patients with active severe Wegener’s granulomatosis. Am J Med. 2007;120:643.e9-e14.

- Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, et al. Wegener granulomatosis: An analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:488-498.

- Hauer HA, Bajema IM, van Houwelingen HC, et al. Renal histology in ANCA-associated vasculitis: Differences between diagnostic and serologic subgroups. Kidney Int. 2002;61:80-89.

- Said G, Lacroix-Ciaudo C, Fujimura H, Blas C, Faux N. The peripheral neuropathy of necrotizing arteritis: A clinicopathological study. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:461-465.

- Gunnarsson R, Omdal R, Kjellevold KH, Ellingsen CL. Wegener’s granulomatosis of the prostate gland. Rheumatol Int. 2004;24:120-122.

- Davenport A, Downey SE, Goel S, Maciver AG. Wegener’s granulomatosis involving the urogenital tract. Br J Urol. 1996;78:354-357.

- Walton EW. Giant-cell granuloma of the respiratory tract (Wegener’s granulomatosis). Br Med J. 1958;2:265-270.

- Reinhold-Keller E, Beuge N, Latza U, et al. An interdisciplinary approach to the care of patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis: Long-term outcome in 155 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1021-1032.