Artur Szczybylo / shutterstock.com

In 2005, a workforce study conducted by the ACR projected a shortage of 2,500 rheumatologists by 2025.1 This resulted in an increase in the number of rheumatology fellows trained and the development of online training programs for nurse practitioners and physician assistants in rheumatology.

In 2014, Daniel Battafarano, DO, MACP, was a member of the ACR’s Rheumatology Training & Workforce Issues Committee, which recognized that nearly a decade had passed since the initial workforce study. He and colleagues led a new and comprehensive workforce study that was published in the April 2018 issue of Arthritis Care & Research.2 It had a number of goals: to identify demographic employment trends, assess patient access to care and look for potential solutions to address or account for shortages.

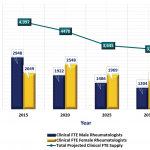

Unfortunately, the new study shows the situation is not improving. By 2025, it projects a shortage of 3,269 rheumatology professionals (physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants). By 2030, demand is expected to outpace supply by 102%—the study predicts a shortage of more than 4,000 rheumatology providers.

“It’s an OMG for rheumatologists, and an OMG reality check for most medicine and surgery,” says Dr. Battafarano, professor of medicine at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences and rheumatology fellowship program director at San Antonio Military Medical Center. “The U.S. is not ready for this in 2025.”

The study found wide discrepancies in the availability of rheumatology professionals in each state, with more rheumatologists concentrated in urban and suburban areas of the U.S. while rural areas suffer significant gaps (what Dr. Battafarano and the study refer to as a “geographic maldistribution”).

Dr. Battafarano

“Patients will have trouble getting access to rheumatologists” by 2025, Dr. Battafarano says. This is true across the board, but especially in the Central U.S., the Southwest, Southeast and Northwest, based on a provider distribution rate per 100,000 patients.

“In the Northeast, it looks pretty good right now (with about three rheumatologists per 100,000 patients). [There’s] a density of medical and training programs, and a lot of rheumatologists are training there and staying there,” says Dr. Battafarano, noting that the current acceptable rate is roughly 1.60 providers per 100,000. “What’s undeniable is that by 2025, the rates will be terrible everywhere.”

The updated workforce study also took a deep dive into the shifting demographics of the rheumatology workforce, which Dr. Battafarano sees as representative of most of medicine, although this was not tested in the study.

The study predicts a shortage of more than 4,000 rheumatology providers [by 2030]. ‘It’s an … OMG reality check.’ —Dr. Battafarano

“Looking at the rheumatology workforce is a reflection of the American workforce,” he explains. “We have retiring baby boomers being replaced by a millennial workforce that is leapfrogging gen-Xers, because they outnumber them, … it’s happening in corporate America and it’s happening in healthcare.”

The updated workforce study—the 2015 ACR Workforce Study—first utilized a series of surveys to collect data on factors underlying both supply and demand within the rheumatology specialty and among patient populations. It then used these data, with multiple references, to establish assumptions for a sophisticated model that resulted in an integrated workforce framework considering both best-and worst-case scenarios.

Supply factors included geographic distribution of rheumatology professionals, productivity, retirement, gender, practice setting, characteristics of new graduates and changes in the number of non-physician providers.3 Unique to this workforce study, it also estimated the number of anticipated full-time and part-time adult rheumatology providers.

“This has not been done to this level of detail in other workforce studies,” says Dr. Battafarano, who explains that full-time rheumatologists were defined as working in a non-academic clinical setting five days a week for eight hours a day. Academic providers, like him, were considered 0.5% full-time equivalent; 50% of their time is dedicated to seeing patients and 50% is dedicated to teaching and research.

Demand factors included patients with osteoarthritis as 25% of the patient load, the population of people over age 65 between 2015–2030, and the prevalence of adult doctor-diagnosed arthritis.

“We performed patient surveys where we asked rheumatology patients questions about access to care and their demands for access to care, the time they traveled to see a doctor and simple questions along those lines that contribute to demand for what patients need,” says Dr. Battafarano.

The study found that between now and 2030, two rheumatologists are anticipated to retire for every new rheumatology fellow graduate.

“We can train more rheumatologists but the gap is so severe that even if we increase the total number of rheumatologists being trained, it will not close the gap significantly,” Dr. Battafarano says.

Rheumatology nurse practitioners and physician assistants are anticipated to increase between 2 and 5%. At the same time, women rheumatologists, currently about 41% of the rheumatology workforce, will shift to 57% of the workforce by 2025. The number of part-time rheumatologists will also increase. Overall, retirements, a future millennial workforce, a gender shift and an increase in part-time rheumatology providers will result in an overall decrease in access to care and in the total number of patients being seen by rheumatologists.

Dr. Battafarano elaborates on several points. For one, he says, “medical students, physician assistants and nurse practitioners aren’t learning enough musculoskeletal medicine in school but they should be exposed to it more, both in hopes of recruiting but also to enhance their clinical skills. It’s important to train the providers who may not have the luxury to refer to rheumatology for patients that could be managed by primary care. … In 10–15 years, we are going to want rheumatologists to be fully engaged primarily in rheumatologic disease and treatment, not patients with primary care problems like tendinitis.”

7 Opportunities for Change

Addressing the anticipated shortages will not be easy, although fortunately, a number of opportunities exist. Dr. Battafarano lays out the following:

- Increase the number of training programs, particularly in underserved regions;

- Increase the recruitment of physician assistants and nurse practitioners into rheumatology;

- Better educate non-rheumatology providers in musculoskeletal medicine to empower them to manage primary care musculoskeletal disease;

- Offer loan forgiveness for rheumatologists willing to work in underserved areas;

- Embrace telemedicine to provide and/or triage rheumatological care;

- Facilitate primary care musculoskeletal medicine to physical therapists and occupational therapists; and

- Build more interdisciplinary communities to provide additional support and fill gaps.

“The rheumatology workforce challenge is just part of the story and is starting to parallel what’s happening in healthcare,” says Dr. Battafarano. “Other specialties looking at our study will see similar trends occurring in their workforces.”

Kelly April Tyrrell writes about health, science and health policy. She lives in Madison, Wis.

Disclaimer: The view(s) expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of San Antonio Military Medical Center, Brooke Army Medical Center, the U.S. Army Medical Department, the U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General, the Department of the Army, Department of Defense or the U.S. government. The primary author is an employee of the U.S. government.

References

- Deal CL, Hooker R, Harrington T, et al. The United States rheumatology workforce: Supply and demand, 2005–2025. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2007 Mar;56(3):722–729.

- Battafarano DF, Ditmyer M, Bolster MB, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Workforce Study: Supply and demand projections of adult rheumatology workforce (2015–2030). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018 Apr;70(4):617–626.

- Bolster MB, Bass AR, Hausmann JS, et al. The role of graduate medical education in adult rheumatology. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Jun;70(6):817–825.