Bottom line: If there are sudden ocular symptoms, call your ophthalmic colleagues and also investigate for further serious systemic concerns on the horizon.

2. When You Get a Referral from Ophthalmologists, Encourage Them to Be as Specific as Possible

Esen K. Akpek, MD, professor of ophthalmology and rheumatology; director, Ocular Surface Disease and Dry Eye Clinic, and associate director, Johns Hopkins Jerome L. Greene Sjögren’s Syndrome Center, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, believes her ophthalmic colleagues need to be more detailed regarding a patient’s signs and symptoms when referring to a rheumatologist. They should also list any possible systemic diagnoses and what drugs could be appropriate.

The lesson for rheumatologists: Ask eye doctors to get specific, because the information they provide is crucial for you to order the appropriate workup. “If you don’t do the proper workup, you can never get the right diagnosis,” Dr. Akpek says.

By getting detailed, the ophthalmologist and rheumatologist can get to the heart of the problem. Dr. Akpek also encourages rheumatologists to pick up the phone at least once to discuss a patient’s collaborative care with an ophthalmologist—something that sounds obvious but does not happen often enough, she adds.

That said, remember that ophthalmologists often stay focused on the eye, meaning their exam results may prevent them from fully considering systemic diagnoses, says George Nick Papaliodis, MD, director, Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Service, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston. Dr. Papaliodis is board certified in both internal medicine and ophthalmology. “They may not examine any organ aside from the eye, so the underlying diagnosis may elude them,” he says. That’s why he encourages ophthalmologists to consider nonophthalmic symptom severity and frequency when making a referral to a rheumatologist.

3. Be Careful with Those Steroids

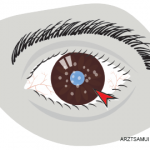

Excessive steroid use can lead to an elevated intraocular pressure (one risk factor for glaucoma) and increase the risk for cataracts. However, it’s common for physicians outside of ophthalmology to prescribe steroids to patients without monitoring their use, says Dr. Akpek. A better idea is to refer to an ophthalmologist if steroid use is involved in the patient’s care to help monitor intraocular pressure and weigh in if steroid use is excessive, Dr. Akpek says (see the sidebar to the right for more referral suggestions).

Two relatively newer corticosteroid implants that ophthalmologists are using for chronic noninfectious uveitis are Retisert (fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant) and Ozurdex (dexamethasone intravitreal implant), which can be placed in the eye for two-and-a-half years and six months, respectively, Dr. Papaliodis says. However, even those advances require monitoring for the avoidance of long-term steroid effects.