Depression is a serious brain-based condition affecting mood, participation in important life activities, quality of life and mortality. It can be considered a spectrum disorder, because many depressive symptoms may be present only occasionally or occur at a level that does not cause significant distress. It’s the persistence and intrusiveness of these symptoms that distinguishes depression from normal mood fluctuations. Despite effective interventions, only half of people with depression in the U.S. are accurately diagnosed, and of those, only 41% receive adequate care.1

Presentation of Depression

Depression is caused by a complex interplay of biological, social/environmental and psychological factors. Evidence demonstrates that people who are routinely exposed to high levels of stress, such as those with low socioeconomic status, exposed to violence and/or those who have chronic health conditions, experience increased levels of depression. The rates of depression for people with chronic health conditions is two to three times higher than the rate for the general population, and people who have three or more conditions will have seven times the rate of depression.2 In addition, chronic illnesses create physical and emotional stress, which exacerbates the symptoms of pre-existing depression.3,4 Depression causes feelings of sadness, emptiness and loss of interest in participating in life activities (i.e., anhedonia). Although some individuals with depression demonstrate apathy or lethargy, others may become irritable and angry. Depression also produces cognitive symptoms, such as inability to concentrate or focus and poor attention and memory. Studies have demonstrated depression also leads to declines in executive functions controlled by the prefrontal cortex.5

Depression is often present prior to the onset of chronic illnesses, including arthritis, cardiovascular disease and diabetes, and may trigger an existing vulnerability to those conditions. A 12-year prospective study followed 5,992 healthy individuals (mean age 58 at baseline) who were free of chronic illness and found that 5.2% of study participants had depression at baseline. Over the course of the study, 45% of participants developed arthritis, 19% had cardiac conditions, 13.9% developed diabetes, and 10.6% developed cancer.4 The impact of depression on all of these conditions except for cancer was statistically significant. Patients with osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have a very high prevalence of comorbid depression.3,6 It’s not surprising that chronic illnesses, including arthritis, appear to trigger the onset of depression by imposing pain, fatigue and activity limitations on affected individuals. Nosek reported that 51% of women with physical disabilities had mild depression and 31% were moderate to severely depressed.7 When mental illness coexists with other medical problems, it can affect the onset, progression and outcome of those disorders, increasing both morbidity and mortality.3 Having a psychiatric disorder with a physical condition can complicate the care of both conditions, causing the medical condition to be of longer duration and become more complicated and more difficult to treat. It also negatively affects a patient’s ability to adhere to medical regimens.8,9

Individuals with depression report constant fatigue & often ‘look’ depressed, with a slouched posture, unkempt appearance & slowed movements. These somatic complaints are an underappreciated symptom of depression.

The essential features of a major depressive episode must occur most of the day, every day, for at least two weeks. During that time, there is a depressed mood and/or the loss of interest and pleasure in most activities the person once enjoyed. While substantially impairing an individual’s ability to function at work or school and to cope with daily life stresses, depression should also be viewed as a life-threatening illness, because the risk of suicide is high.

It’s a disorder that can be reliably diagnosed and treated by nonspecialists as part of primary healthcare. Specialist care is needed for a small proportion of individuals with complicated depression or those who do not respond to first-line treatments. The earlier the treatment begins, the more effective it is.

In addition to mood, anhedona and cognition, depression also affects neurovegetative functions, leading to changes in eating and sleeping patterns, with affected individuals doing too much or too little. Individuals with depression report constant fatigue and often “look” depressed, with a slouched posture, unkempt appearance and slowed movements. These somatic complaints are an underappreciated symptom of depression.

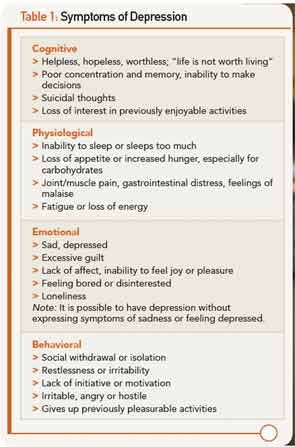

Overlapping symptoms of physical and psychiatric symptoms in co-occurring conditions can create significant barriers to diagnosis. In fact, more than 90% of clients with depression manifest physical symptoms, including muscle or headaches, weakness, gastrointestinal problems, faintness or dizziness, or sensory impairments. Pain occurs frequently with depression, and there is a corollation between the severity of the depression and the severity of the pain.10 Table 1 summarizes the symptoms of major depressive disorder (MDD). The diagnostic focus of these symptoms typically turns to the diagnosis of the physical symptoms without considering depression.

The Need for Appropriate Screening

Care providers are likely to see many clients with undiagnosed depression who come for treatment, and appropriate screenings can lead to a diagnosis and effective intervention. Further, many people with depression “self-medicate” with drugs or alcohol, which exacerbates the effects of depression and worsens overall health. Use of a well-designed screening tool is a valuable adjunct to the information typically gathered during a physician visit.11 However, many patients may present in ways that are atypical or present barriers to recognition.

Older adults with depression present with physical symptoms more than feeling sad or depressed. Fatigue, insomnia, loss of appetite and pain are frequently reported, as well as feeling in “low” spirits.12 Depression negatively affects activity levels, memory, cognition and problem solving, which are also problems frequently seen in older adults.13 In addition, they are more likely to be uncomfortable talking about their sadness and under-report their symptoms. The onset of depression appears to be a significant factor leading to nursing home placement and suicide, further increasing the burden of illness that older adults experience.14 Some care providers mistakenly believe these symptoms are a “normal” part of aging, and too often attribute them to an inevitable component of aging. Conversely, the overlap of symptoms that occur with aging and those that occur with depression may lead to the over-diagnosis of depression.15

Another important factor in the identification of depression is cultural norms, which affect how people interpret the symptoms of depression and their cause. “Indeed, evidence exists that even the specific symptoms associated with such psychiatric conditions as depression show impressive cultural variability.”16 Some cultures do not have a word or phrase that describes depression, and others, such as the Chinese, experience symptoms that are physical rather than emotional. Patients from traditional Chinese cultures will express being “bored” and feeling fatigue, pain, dizziness and generalized discomfort, but not sadness.17

To provide optimal care for individuals from ethnic and cultural minorities with depression, we must understand and accommodate their beliefs when we explain etiology and treatment options. For example, 63% of African Americans believe that depression is caused by personal weakness, and two-thirds believe that prayer is the most effective form of treatment.18 They typically refer to depression as “having the blues” and attribute it to stressful life events. For some ethnic groups, conforming to the norms of the group and including their opinions and desires are essential components of care, even superseding what individuals or professionals might think is best. This may deter some patients from seeking care and contribute to higher dropout rates from treatment.19

Another concern that applies to depression screening tools is that they might be incompatible with patients from some minority cultures, especially non-English speakers.20 In this case, when words in the tool are translated literally, they may lose their intended meaning. Other times, the symptoms that are described are actually accepted behaviors in a particular culture. For example, in Latino cultures crying is not only prevalent, but an expected behavior in certain situations. Further, questions that ask whether the patient perceives that “people don’t like me” or people are “unfriendly” are common beliefs in the African American community, which has experienced significant racism.20

Prevalence of Depression with Arthritis

Research indicates that there are high levels of co-occurrence between OA, RA and depression. Prevalence rates in RA are reported to be in the range of 9.5–41%, and the prevalence for patients without RA is closer to 4.5%.20 There are multiple reasons why there is so much variability in these reported rates. A recent article in Rheumatology reviewed 72 articles, which examined co-occurrence of RA and depression. In these articles depression was measured using 40 different definitions and there may have been significant discrepancies for how depression was diagnosed. Further, studies used a variety of screening tools, and even within the same tool, used different cutoff points for diagnostic purposes. Therefore, the same tool may have revealed different rates of depression. Some of the studies reported on were of poor quality or used small samples. However, this review reveals that for patients with comorbid depression and RA, there are poorer health outcomes with increased pain, additional comorbidities and higher rates of mortality.20

Most notable for professionals working with patients with arthritic conditions is the fact that higher levels of depression are associated with increased levels of pain, fatigue, physical distress, levels of disability, worse outcomes following knee replacement, poorer overall health and greater use of healthcare resources.8,9,15 Generally, the more severe the depression, the greater the number and intensity of physical symptoms, which are accompanied by significant restriction of life activities.10 Typically, arthritic patients with depression will present to their care providers with physical symptoms that are seen in both arthritis and depression. As noted above, each of these conditions increases both the symptoms and disease burden of the co-occuring conditions, including joint pain, loss of energy, poor sleep, poor appetite and fatigue. Healthcare providers who treat patients with arthritis must be aware of the impact of this comorbidity and consider depression screening for all patients, but most especially for those patients whose arthritis symptoms increase in severity.

Effectiveness of Screening Tools

The gold standard for diagnosing depression is a structured, or semi-structured, interview by a mental health professional. However, this is neither feasible nor necessary. Multiple screening tools are available that can be easily administered in medical settings. Efficacious tools need to have both good sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity will rule in, or yield, an accurate number of patients with the condition being screened. Test specificity, on the other hand, will rule out or exclude patients who do not have the target condition without identifying too many false negatives. A concern with test specificity is that too many affected individuals will be missed. Test sensitivity and specificity that are close to 1 are desirable, and .8 is considered good. A test with a sensitivity of .8 will capture 80% of patients who have the disorder being screened for. A specificity of .8 will rule out 80% of patients without the target condition.21

Prevalence rates on these tools will be affected by the threshold for a positive screen that can be raised or lowered to suit the preferences of the examiner. Patients who screen positive for depression will need to be followed up with a structured or semi-structured interview to determine its actual presence.

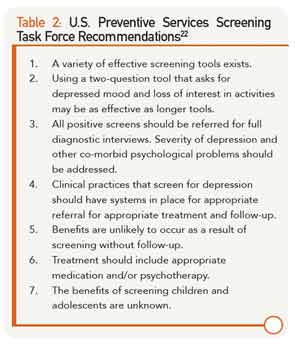

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has developed recommendations for depression screening in medical settings.22 They found there is ample evidence that depression screening improves the identification of depression in primary care settings and improves outcomes for patients. A summary of their recommendations is found in Table 2. All positive screens should be referred for a follow-up diagnostic interview. The best outcomes have resulted when the depression results are communicated with patients and other relevant professionals to facilitate effective intervention and follow-up. Screenings in isolation from intervention and follow-up do not improve outcomes.

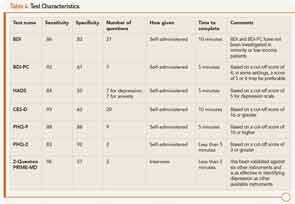

A variety of screening tools is available and most have good sensitivity, with scores in the .8 to .9 range. Specificity is typically adequate but not as accurate, with scores ranging from .70 to .85. The results of the USPSTF investigations into appropriate tools found that “There is little evidence to recommend one screening method over another, so clinicians should use the method that best suits their personal preference, the patient population served and the practice setting.”22 In fact, a two-question screen known as the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) is as effective as longer tools.

An issue in the selection of appropriate screening tools for healthcare providers caring for people who are ill—and especially for those with arthritis—is the number of questions that ask about somatic symptoms that overlap with symptoms of illness and arthritis. Such a tool would give a high false-positive rate. The Beck Depression Index (BDI) is the most frequently used screening tool worldwide. Other frequently used patient self-report screenings include the:

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS);

- Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression (CES-D);

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9);

- PHQ-2; and

- Two questions from the PRIME MD.

All of these will be discussed below.

The Tools

The BDI was developed by Aaron Beck in 1961, and revised in 1996 with the newer version known as the BDI-II. The test consists of 21 items that are scored from 0 (not present) to 3 (present to a significant degree). It is typically given to the patient to self-complete or can be read aloud to a patient with a verbal response. It depends on a fifth- or sixth-grade reading level and was validated on a white, middle-class population, so its usefulness in minority patients is uncertain. The BDI and BDI-II ask for the cardinal signs of depression, including indicators of mood, cognition and somatic symptoms. This last category is problematic for use in a medical setting. Therefore, the BDI for Primary Care (BDI-PC) was developed for use in settings in which patients might be expected to have physical symptoms that overlap depression.23 The BDI-PC contains no questions relative to somatic symptoms, but includes questions that assess such symptoms as sadness, pessimism, past failures, loss of pleasure and thoughts of suicide.

The test does not come with a standard cut-off point for a positive screen, which is to be determined by the examiner based on information about the context of the clinical setting. Administration of the BDI-PC to 120 patients making non-mental health-related visits to physicians found that a cut-off score of 4 out of a possible 21 points was clinically significant.23 In this study population, the sensitivity was .97 with a specificity of .99.23

Another frequently used screening tool is the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which was designed to be used with patients who are receiving medical care. Thus, the tool has the advantage that it does not contain any questions that refer to somatic symptoms. This test is the most widely tested of all the screening tools among patients with co-occurring medical conditions and has strong validity when compared with other validated tools. Further, the findings remain valid when compared to the structured mental health interview.24

The HADS contains 14 items, seven for depression and seven for anxiety. Taken together, they reflect mental disorders. Each item is scored on a four-point scale from 0 (not present) to 3 (present to a considerable degree). One review found that a cut-off score of 5 for depression produced optimal specificity and sensitivity.21 However, another investigation in patients seen in general medical practice found the best information came with a cut-off score of 8 or higher.11

The CES-D was developed for use in a general medical setting. It is a 20-item scale that asks the patient how frequently they have experienced certain symptoms over the past week. Each item is scored from 0 (no days or rarely) to 3 (five to seven days). Thus, it yields a score from 0–60. A cut-off score of 16 or greater is highly indicative for depression. Some of the 20 questions, such as lack of appetite, having restless sleep and feeling everything required great effort, ask for symptoms that overlap with symptoms of arthritis. Studies indicated that the CES-D had only moderate agreement with a structured interview.

In a study of elderly patients, the sensitivity was 100% and the specificity 88%, compared with a sample of patients in a primary clinic in which the specificity was 79.5% and the specificity was 71%.25 In patients with RA, a cut-off score of 19 was most appropriate due to overlapping symptoms of RA and depression.26

Caracciolo and Giaquinto studied patients with neurological and orthopedic conditions receiving rehabilitation because depression is quite common in patients receiving these services.25 They chose to use the CES-D because it has good psychometric properties among patients with a variety of medical conditions and found it was appropriate for use with older adults and patients who are ill. In their study of patients with orthopedic conditions, including fractures and joint arthroplasties, the CES-D had a sensitivity of 100% with a specificity of 57%. The rates were almost identical for patients with neurological conditions.

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a nine-question tool that can be completed by patients in a few minutes. It can be administered by the clinician, via self-report or over the phone. The nine questions of this screen were selected because they asked for the symptoms of depression as identified in the DSM-IV. Like several other tools, it provides a score of 0–3 for each item, but asks the patient to identify how often the symptom is present rather than how severe the symptom is. There are check-off boxes for “not at all” (0) to “nearly every day” (3). A scoring rubric is provided for the examiner, which can be completed in a few minutes and can rate a patient’s level of depression from minimal to severe.

Two symptoms on the PHQ-9 are more significant than others. They ask if over the past two weeks the patient has been bothered by any of the following problems: “Little interest in doing things” and/or “Feeling down, depressed or hopeless.”27,28 One or both of these questions must be present for more than half the days or nearly every day in order to screen positive for depression.27,28 In addition to symptoms being present, they must cause distress in social, occupational or other areas that are of importance to the patient. As the frequency of the depressive symptoms increases, patients are less able to function in daily life skills, used more sick days from work and used the healthcare system more frequently. For this reason, a 10th question asks the patient who has checked any box that is greater than 0 to indicate how difficult this symptom made it for the patient to work, take care of things at home or get along with people. The response to this item alone is an excellent marker for functional impairment.27,28

In addition, a yes to Question 9, which asks about thoughts of self-harm and/or suicide, is also diagnostic.

The healthcare provider is instructed to follow up the checklist with an interview to verify the answers and to place the answers in context. Studies have demonstrated that a cut-off score of 10 or higher yields a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 88% for major depression.28 Of the nine items on the scale, three (energy, eating and sleep) are also present in people who have arthritis, which can make it problematic for use in this population.

A scaled down version of the PHQ-9 is the PHQ-2. This shorter version contains only two questions that are effective for performing a screen without rating the severity of the depression. It’s appropriate for use in a busy practice in which the provider must screen for and collect information about many health-related conditions.29 In the PHQ-2, the two relevent questions ask for the frequency of two symptoms over the past week. They are having a depressed mood and loss of interest in activities. The possible scores run from 0–6. A cut-off score of 3 or greater yielded a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 92%. Further, as the scores increase, difficulty performing important life activities, such as going to work and healthcare use, increase.29 This two-question tool is as effective as longer screens and does not contain any questions that overlap with the symptoms of arthritis.

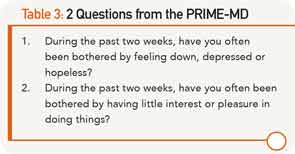

The PRIME-MD is another frequently used, validated tool to measure depression. It consists of 27 questions (see Table 3). However, it has been reported that a “yes” answer to one of two critical questions had 86% sensitivity and 75% specificity, compared with a subsequent telephone interview diagnosis of MDD.30

Health professionals should include screening for depression so as to improve treatment adherence, patient quality of life and clinical outcomes, including pain, fatigue & poor sleep.

Whooley et al carried out a study of 536 patients attending a VA hospital to determine the efficacy of using these two questions with a simultaneous interview to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the tool. Another goal of this study was to determine the validity of these two critical questions compared with six previously validated screens.

The two questions were selected because they asked for the essential features of MDD (depressed mood and loss of interest in activities), which occurred over a period of at least two weeks. The two questions selected from the PRIME-MD questionnaire are: 1) “During the past two weeks, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?” and 2) “During the past two weeks, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?”30

The two-question screen was found to be a valid and effective means of identifying subjects with major depression, with a specificity of 96% and a specificity of 57%. A “no” response to both questions made depression highly unlikely. The test results were similar across all ages. However, a limitation of this study was that few of the patients were women.

Conclusion

Depression is a condition that frequently co-occurs in patients with chronic health conditions, including OA and RA. Health professionals working with these patients should include screening for depression so as to improve treatment adherence, patient quality of life and clinical outcomes, including pain, fatigue and poor sleep. Effective tools are available, and they are brief enough to be used in a busy medical practice (see Table 4). In fact, a two-question screen is as effective as longer tools in identifying patients with depression.

Nancy Sharby, PT, DPT, MS, is associate clinical professor in the Department of Physical Therapy at Northeastern University, in Boston, Mass.

References

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Co-Morbidity Survey Replication. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–3105.

- Martin K. Providing support for people with depression. Practice Nursing. 2013;24(3):133–136.

- Chapman DP, Perry GS, Strine TW. The vital link between chronic disease and depressive disorders. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(1): published online http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2005/jan/04_0066.htm.

- Karakus MC, Patton LC. Depression and the onset of chronic illness in older adults: A 12-year prospective study. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2011;38(3):373–382.

- Murphy FD, Sahakian BJ. The neurobiology of bipolar disorder. Brit J Psychiat. 2001;Suppl 41:s120–s127.

- Gleicher Y, Croxfore R, Hochman J, et al. A prospective study of mental health care for comorbid depressed mood in older adults with painful osteoarthritis. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:147.

- Nosek MA, Hughes RB, Robinson-Whelen S. The complex array of antecedents of depression in women with physical disabilities: Implications for clinicians. Disabil and Rehabil. 2008;30(3):174–183.

- Katon W, Lin EHB, Kroenke K. The association of depression with medical symptom burden in patients with chronic medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiat. 2007;29:147–155.

- Wing RR, Phelan S, Tate D. The role of adherence in mediating the relationship between depression and health outcomes. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:877–881.

- Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al. Cost of lost productive work time among U.S. workers with depression. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3135–3144.

- Olsson I, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression rating scale: A cross-sectional study of psychometrics and case finding abilities in general practice. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:46.

- Butcher HK, McGonigal KM. Depression and dispiritedness in later life. Am J Nurs. 2005;105(12):52–61.

- Alexopoulous GS, Raue PJ, Sirey JA, et al. Developing an intervention for depressed chronically ill elders: A model from COPD. Int J Geriat Psych. 2007;23:447–453.

- Harris Y, Cooper JK. Depressive symptoms in older people predict nursing home admission. J Am Geriat Soc. 2006;54:593–597.

- Lewinsohn PA, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, et al. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Depression (CES-D) as a screening tool for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging. 1997;12(2).

- Karp D. Speaking of Sadness. New York, N.Y. Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Kleinman A. Culture and depression. NEJM. 2004;351(10): 951–953.

- Mahon V. Challenges in the treatment of depression. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2006;11(6):366–370.

- Whitley, R. The implications of race and ethnicity for shared decision-making. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2009;32(3):227–230.

- Matcham F, Rayner L, Steer S, et al. The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 2013;52(12):2136-2148.

- Kerr LK, Kerr LD. Screening tools for depression in primary care. Western J Med. 2001;175(5):349–352.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(10):760–764.

- Steer RA, Cavalieri TA, Leonard DM, et al. Use of the Beck depression inventory for primary care to screen for major depressive disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiat. 1999;21(2):106–111.

- Vodermaier A, Millman RD. Accuracy of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1899–1908.

- Caracciolo C, Giaquinto S. Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D). J Rehabil Med. 2002;34:221–225.

- Covic T, Pallant JF, Monaghan G, et al. A longitudinal evaluation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression in a rheumatoid arthritis population using a Rasch Analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;13(5):41.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–616.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Annals. 2002;32:9.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The Patient Health Questionaire: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292.

- Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, et al. Case-finding instruments for depression: Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. Jul 1997;12(7):439–445.