Simone Hogan / shutterstock.com

At the 2021 ACR State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium, Saira Sheikh, MD, associate professor of Medicine and director of the Rheumatology Lupus Clinic, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, provided an update on the past, present and future of the management of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

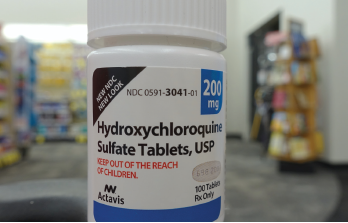

This year, hydroxychloroquine received a great deal of attention, given early reports that it might be beneficial in the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. Clinical trials did not support this hypothesis, and the medication is not recommended for COVID-19 treatment. In fact, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) issued a statement in June 2020 warning that co-administration of remdesivir and chloroquine phosphate or hydroxychloroquine sulfate is not recommended, because it reduces the anti-viral activity of remdesivir.1

Hydroxychloroquine remains a mainstay of lupus treatment and is recommended for all patients with SLE, unless a specific contraindication exists. It’s possible to assess hydroxychloroquine adherence using drug levels in the blood, but insufficient data presently exist to recommend such monitoring in routine clinical practice.

Dr. Sheikh noted the recommended daily dose of hydroxychloroquine is 5 mg/kg of body weight. Additionally, screening for retinopathy with visual field examination and/or spectral domain-optical coherence tomography should be performed at baseline and annually after five years of use.

Treatment Goals

Although Dr. Sheikh remarked that patients with SLE often describe intangible symptoms, such as fatigue, brain fog and depression, which require further research to understand and treat, an overarching goal in the management of SLE should be a treat-to-target approach. In this regard, the concepts of remission of disease and lupus low disease activity state (LLDAS) can be employed.

In Dr. Sheikh’s presentation, remission indicates the absence of disease activity and steroid use in patients with SLE who are being managed with hydroxychloroquine alone. For LLDAS, this goal indicates an SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) score of less than 4, with no activity from major organ systems; a Physician Global Assessment of less than 1, with no new activity; a prednisone dose of less than 7.5 mg daily; and standard doses of antimalarials, immunosuppressives and biologics.

How can clinicians achieve these goals? For lupus nephritis, Dr. Sheikh indicated that at least three years of treatment, including one year of complete clinical remission, should be achieved before considering withdrawal of immunosuppression.

When such withdrawal occurs, the potential risks include increased disease activity and flares, worse renal outcomes, and increased morbidity and mortality.

Complicating the matter is that, often, a discrepancy exists between clinical and histologic responses to treatment, with 30% of patients categorized as complete responders demonstrating histologic evidence of activity on renal biopsy, which is strongly predictive of a subsequent renal flare when reducing immunosuppression.