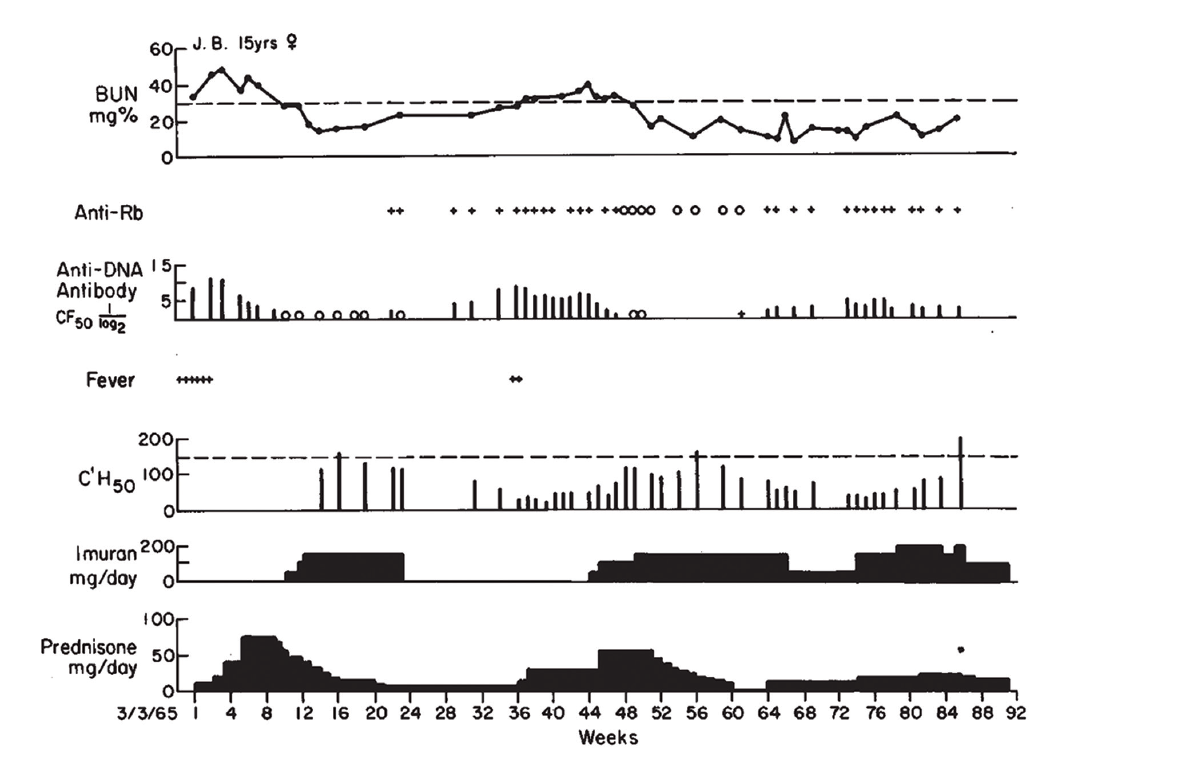

(click for larger image) Figure 1: Clinical Course of J.B., with Association of Antibodies to DNA, Rb & Low Serum Complement Levels, with Active Nephritis

Reprinted with permission, The New England Journal of Medicine ©1968.

Dr. Pisetsky relates that he still uses Figure 1 from the paper when he lectures about lupus nephritis. “Each part of the figure has something important. One is renal disease is an important feature of active lupus, and while the [blood urea nitrogen] goes up, it can respond to therapy. Right below that in the figure, in the anti-DNA levels, the level goes up and comes down and goes up and comes down. And that kind of variation is just about unique to anti-DNA. And when you start treating, the antibody can go away.”

Citing this paper and earlier work, Dr. Schur and Dr. Sandson concluded the low levels of complement observed in these patients most likely reflected the fixation of complement by antibody-antigen complexes on the renal glomerular basement membrane in patients with lupus nephritis.1 It was Dr. Schur’s first paper in The New England Journal of Medicine. “I was really proud of it,” he relates.

Lasting Impact

Since its initial publication in 1968, the paper has been cited over 600 times. Dr. Pisetsky explains, “These basic observations led to a lot of new ideas about what immune complexes could do, but also how nucleic acids could stimulate the immune system.” Many of the key elements pulled together in the article are still being investigated using more sophisticated technology.

The changing nature of this particular subset of anti-nuclear antibodies still remains a mystery. Dr. Pisetsky sees the variation in levels of anti-DNA as a fundamentally important question in immunology. He asks, “Why do these anti-DNA levels go up and down in some patients? Why don’t they just stay up? These correlations between kidney disease and anti-DNA antibodies point to a pathogenic role, but the details are not so clear.”

Dr. Pisetsky contrasts response to DNA with antibodies in people who get immunized or experience natural infections, in whom antibodies often remain high for many years. But the anti-DNA antibodies in these lupus patients seem not to have a long-lived production or memory. “What it says is that the B cell populations that are producing these antibodies have a special kind of regulation. Further, the B cells that make anti-DNA appear different from those that make other autoantibodies. That’s a major focus of research,” he says. Relatedly, it is still not known why and how steroids and other treatments are able to lower the levels of anti-DNA so dramatically.

Questions still remain about the mechanisms of immunopathology underlying the formation of these immune complexes and their relationship to kidney disease. Dr. Schur explains that the immune complexes seem to form between antibodies to DNA and tend to deposit in the kidney. He adds, “Once they have deposited in the kidney, they initiate an inflammatory response with the activation of complement. This then attracts white cells to where the immune complexes are deposited, setting up an inflammatory reaction. As a result, you get nephritis. But why they deposit preferentially in the kidney is still not clear.”

Dr. Pisetsky notes, “One of the parts of the study that I like particularly is that Schur and Sandson were also able to measure free DNA in the blood. That’s a very important observation, because it means that DNA gets outside of cells.” A couple of years earlier, Dr. Schur and others in Dr. Kunkel’s lab had also described free DNA in the blood of lupus patients.4 Dr. Pisetsky remarks that lupus was one of the first places where people looked for free DNA; however, now techniques to detect circulating DNA (“cell-free” DNA) are used in many other medical applications, such as in diagnosing malignancies and in prenatal assessments.

Further work on the relationship between DNA and the immune system has opened whole new avenues of investigation. These have been important not only for autoimmune rheumatological diseases, but also in our understanding of host defense and cancer. Ultimately, the work of Dr. Schur and others in the field led to the discovery that immune complexes stimulate cytokines, such as type 1 interferon.

Dr. Pisetsky explains, “What investigators have now shown is that the immune complexes of DNA and anti-DNA and other nuclear molecules can stimulate cytokine production by immune cells. That production relates to sensors on the inside of cells for DNA. So DNA actually plays a very important role in host defense on the inside of cells, not just the outside.” Researchers are now actively working to describe these internal sensors for DNA and RNA that generate cytokines and inflammation.

Dr. Pisetsky continues, “The activity of these immune complexes also suggests a mechanism for stimulating inflammation in the kidney. These complexes induce inflammation, not just by fixing complement, but by shuttling the DNA inside the cell to stimulate the internal sensors.” Research has also demonstrated that these anti-DNA antibodies may regulate the gene expression of inflammatory and fibrotic signals in renal cells.7