nukeaf / shutterstock.com

Over 50 years ago, an article appeared in The New England Journal of Medicine: “Immunologic Factors and Clinical Activity in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.”1 Written by a young postdoctoral fellow, Peter H. Schur, MD, and colleagues, the article synthesized important work in the field at the time. What follows is a discussion of the historical context of the paper and its lasting impact.

A Modern Understanding of Lupus

Our modern understanding of lupus began when Malcolm Hargraves, MD, and Robert Morton, MD, first described the lupus cell in 1948.2 David S. Pisetsky, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and immunology at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C., describes the phenomenon. “Basically, if you take the blood of patients with lupus, agitate it, incubate it and come back in a little while, what you see is the nuclei of cells that have been engulfed by other cells, called phagocytes.”

Eventually the factor that induced lupus cell formation was shown to be a gammaglobulin, an autoantibody.3

Dr. Schur

In the 1950s, researchers ascribed various autoantibodies to different constituents of cell nuclei, termed anti-nuclear antibodies (ANAs).3 Dr. Pisetsky explains, “People had defined anti-nuclear antibodies using a number of assays, but the actual targets of these antibodies were not known. Among the first that was really defined molecularly was DNA.”

This was a surprise, he notes, because no one had thought DNA could serve as an antigen. “At the time it was thought the only setting where these antibodies were observed was in patients with lupus. So that finding really suggested a fundamental difference between immune recognition of DNA in normal individuals and in people with lupus,” he says.

Dr. Pisetsky explains that people didn’t know whether these ANAs caused lupus or were just associated with it. He notes that it was becoming recognized that lupus had characteristics of an immune complex-mediated disease. “It appeared the complexes with anti-DNA were very important and that their presence led to lowering of complement values. In my view, what this paper did was really put everything together. Dr. Schur showed clearly how disease activity varied with elevations of anti-DNA.”

The Genesis of the Seminal Paper

Dr. Schur is now a senior professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. After his residency, he performed research at the Walter Reed Army Institute in Washington, D.C. There, he learned how to do complement fixation tests.

Subsequently, Dr. Schur pursued a fellowship at Rockefeller University, New York City, where he studied under Henry G. Kunkel, MD, an esteemed immunology researcher whose work provided important insights into many immune-mediated diseases. There Dr. Schur worked with other postdoctoral students who were studying lupus. “I developed an assay for quantitating antibodies to DNA, complement fixation, which was much more sensitive than previous techniques, such as the immunodiffusion assay. This was before the assays that we have today. It looked at complement-fixing antibodies,” he says.4

Also at Rockefeller, Dr. Schur collaborated on papers demonstrating that immune complexes of DNA and anti-DNA seemed to be present in the kidneys of many patients with lupus nephritis.4,5 “It was obvious that lupus patients had anti-DNA and that immune complexes were forming between DNA and anti-DNA,” he says. “And they seemed to be involving the kidney.”

Dr. Schur decided to look at some of these values in lupus patients serially over time. Because of the small number of lupus patients at Rockefeller, he volunteered to work in the arthritis clinic at The Bronx Municipal Hospital Center, New York, where he had performed his internship and residency.

Dr. Schur monitored patients clinically and with routine lab tests, such as complete blood counts and blood urea nitrogen assays. From 1964–67, he collected frequent serum samples from 96 patients diagnosed with lupus, 44 of whom had renal disease. As he explained in the 1968 paper,

There have been few sequential studies of immunologic factors during different stages of clinical activity. The present investigation was undertaken not only to study the relation of clinical activity to immunologic factors in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (particularly those with renal disease) but also to determine whether a change in immunologic factors might precede the onset of clinical activity.1

To write up the study, Dr. Schur paired with senior author John Sandson, MD, a young faculty member who had mentored him as a resident.

Dr. Pisetsky

Dr. Pisetsky says a variety of assays then existed that could be used to measure anti-DNA. “We’re going back a long time ago, so the techniques were much more crude than those available today. Nevertheless, it was possible to come up with an effective quantitative assay.”

Dr. Schur performed all the assays himself. Using the Ouchterlony immunodiffusion technique, Dr. Schur identified serum antibodies to various forms of DNA (as well as free DNA) and antibodies to some other nuclear proteins. He also assessed the presence of antibodies to DNA that fixed complement. Additionally, Dr. Schur measured the total serum hemolytic complement, using a bioassay designed to assess the hemolytic potential of the complement system.

Dr. Schur explains that most people now just measure two components of the complement system, C3 and C4, but good assays for those complement proteins were not available at the time. Instead, he used a test known as CH50. While at Walter Reed, he had learned how to do this test, which assesses the entire complement system. Dr. Schur explains that this technique was more sensitive than another one then commonly used to assess the complement system, the Kabat technique.

Dr. Schur and Dr. Sandson found that most, though not all, of the patients with high titers of complement-fixing antibodies to DNA had active renal disease. Not all of the patients who had very low complement levels had active renal disease. But all of the patients who had both high amounts of complement-fixing antibodies to DNA and low serum complement levels had active renal disease. Only 13% of patients with active renal disease had no anti-DNA antibodies and normal complement.1

Dr. Schur notes that it recently had been shown that lupus nephritis patients typically had high anti-DNA and low complement levels.6 That pattern was confirmed in this paper, but a new predictive element was revealed as well.

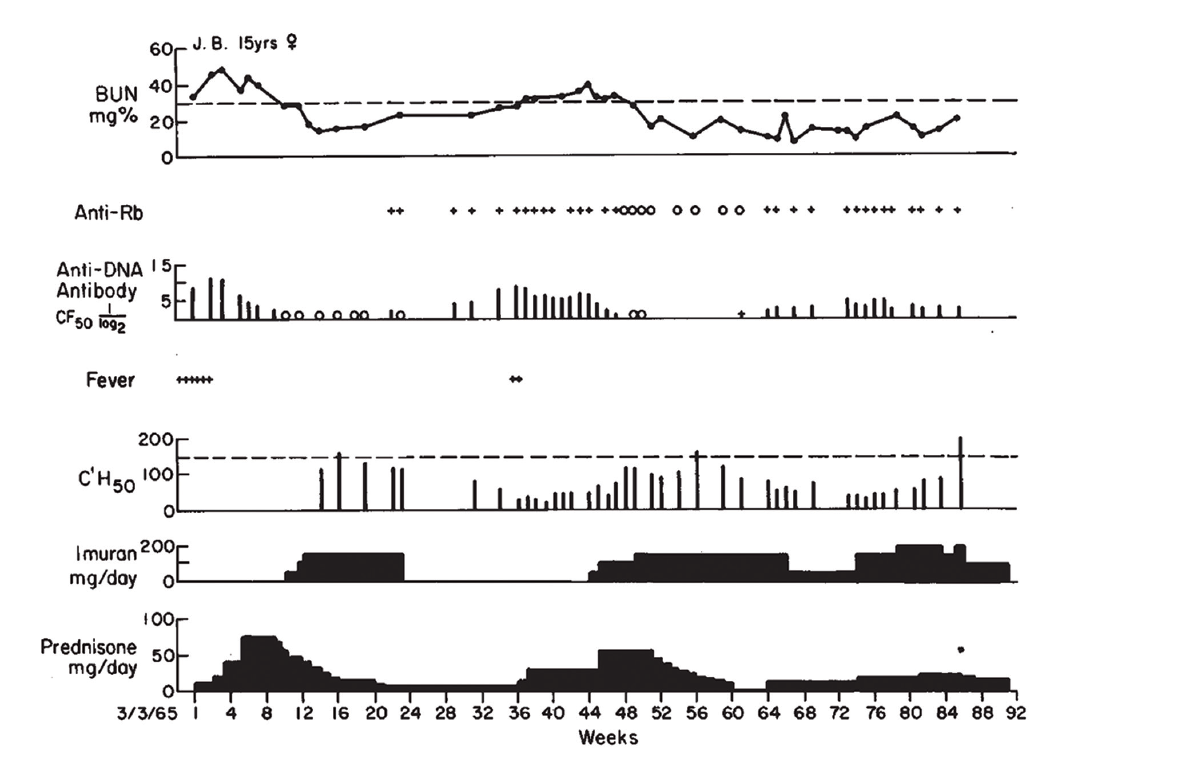

In the paper, Dr. Schur and Dr. Sandson provided a brief case study of a 17-year-old girl with lupus nephritis, J.B. In the article, they tracked her clinical course and laboratory findings and displayed them graphically.

“A pattern began to evolve—it’s shown in Figure 1 as sort of a typical patient,” says Dr. Schur. “As levels of antibody to DNA increased and complement levels diminished, it often preceded a clinical flare. And if you treated them—which at the time was steroids and immunosuppressives—the anti-DNA levels went down and the complement levels went up.”

(click for larger image) Figure 1: Clinical Course of J.B., with Association of Antibodies to DNA, Rb & Low Serum Complement Levels, with Active Nephritis

Reprinted with permission, The New England Journal of Medicine ©1968.

Dr. Pisetsky relates that he still uses Figure 1 from the paper when he lectures about lupus nephritis. “Each part of the figure has something important. One is renal disease is an important feature of active lupus, and while the [blood urea nitrogen] goes up, it can respond to therapy. Right below that in the figure, in the anti-DNA levels, the level goes up and comes down and goes up and comes down. And that kind of variation is just about unique to anti-DNA. And when you start treating, the antibody can go away.”

Citing this paper and earlier work, Dr. Schur and Dr. Sandson concluded the low levels of complement observed in these patients most likely reflected the fixation of complement by antibody-antigen complexes on the renal glomerular basement membrane in patients with lupus nephritis.1 It was Dr. Schur’s first paper in The New England Journal of Medicine. “I was really proud of it,” he relates.

Lasting Impact

Since its initial publication in 1968, the paper has been cited over 600 times. Dr. Pisetsky explains, “These basic observations led to a lot of new ideas about what immune complexes could do, but also how nucleic acids could stimulate the immune system.” Many of the key elements pulled together in the article are still being investigated using more sophisticated technology.

The changing nature of this particular subset of anti-nuclear antibodies still remains a mystery. Dr. Pisetsky sees the variation in levels of anti-DNA as a fundamentally important question in immunology. He asks, “Why do these anti-DNA levels go up and down in some patients? Why don’t they just stay up? These correlations between kidney disease and anti-DNA antibodies point to a pathogenic role, but the details are not so clear.”

Dr. Pisetsky contrasts response to DNA with antibodies in people who get immunized or experience natural infections, in whom antibodies often remain high for many years. But the anti-DNA antibodies in these lupus patients seem not to have a long-lived production or memory. “What it says is that the B cell populations that are producing these antibodies have a special kind of regulation. Further, the B cells that make anti-DNA appear different from those that make other autoantibodies. That’s a major focus of research,” he says. Relatedly, it is still not known why and how steroids and other treatments are able to lower the levels of anti-DNA so dramatically.

Questions still remain about the mechanisms of immunopathology underlying the formation of these immune complexes and their relationship to kidney disease. Dr. Schur explains that the immune complexes seem to form between antibodies to DNA and tend to deposit in the kidney. He adds, “Once they have deposited in the kidney, they initiate an inflammatory response with the activation of complement. This then attracts white cells to where the immune complexes are deposited, setting up an inflammatory reaction. As a result, you get nephritis. But why they deposit preferentially in the kidney is still not clear.”

Dr. Pisetsky notes, “One of the parts of the study that I like particularly is that Schur and Sandson were also able to measure free DNA in the blood. That’s a very important observation, because it means that DNA gets outside of cells.” A couple of years earlier, Dr. Schur and others in Dr. Kunkel’s lab had also described free DNA in the blood of lupus patients.4 Dr. Pisetsky remarks that lupus was one of the first places where people looked for free DNA; however, now techniques to detect circulating DNA (“cell-free” DNA) are used in many other medical applications, such as in diagnosing malignancies and in prenatal assessments.

Further work on the relationship between DNA and the immune system has opened whole new avenues of investigation. These have been important not only for autoimmune rheumatological diseases, but also in our understanding of host defense and cancer. Ultimately, the work of Dr. Schur and others in the field led to the discovery that immune complexes stimulate cytokines, such as type 1 interferon.

Dr. Pisetsky explains, “What investigators have now shown is that the immune complexes of DNA and anti-DNA and other nuclear molecules can stimulate cytokine production by immune cells. That production relates to sensors on the inside of cells for DNA. So DNA actually plays a very important role in host defense on the inside of cells, not just the outside.” Researchers are now actively working to describe these internal sensors for DNA and RNA that generate cytokines and inflammation.

Dr. Pisetsky continues, “The activity of these immune complexes also suggests a mechanism for stimulating inflammation in the kidney. These complexes induce inflammation, not just by fixing complement, but by shuttling the DNA inside the cell to stimulate the internal sensors.” Research has also demonstrated that these anti-DNA antibodies may regulate the gene expression of inflammatory and fibrotic signals in renal cells.7

Markers of Disease Activity

Today, both anti-DNA and complement are still used as markers of disease activity in lupus, particularly for renal disease. Anti-DNA is the only type of anti-nuclear antibody routinely used for this purpose.8

However, not all patients with lupus nephritis show anti-DNA antibodies and/or low complement levels, and not all people with anti-DNA antibodies and low complement levels have renal disease with active flares. These antibodies can be found in some patients who are not experiencing active clinical flares and in some who have never had renal disease. Corresponding to Dr. Schur’s original findings, DNA/anti-DNA complexes clearly aren’t the only elements in play for all patients.

Some investigators have suggested the discrepancy between clinical and serological findings might mean that not all anti-DNA antibodies are truly pathogenic, at least as detected by current assays.7 Notes Dr. Schur, “We now know that low blood complement basically correlates best with type III and type IV nephritis. Not all patients with lupus nephritis have type III or type IV, though it’s well over 50%. And low complement levels don’t correlate that well with other clinical manifestations.”

Dr. Pisetsky explains that, practically speaking, it’s unlikely an increase in anti-DNA antibodies can be used routinely to predict a flare, but it might be immunologically apparent if tested. He describes a lupus patient he recently saw who had a rising creatinine level, for whom he ordered anti-DNA and complement testing. “Now the question is when did that anti-DNA go up? Was it last week? Two weeks ago? Two months ago? We don’t know. So while I’m going to follow the levels, there is always uncertainty,” he says. However, anti-DNA is not a helpful marker in all cases of lupus nephritis.

Many studies have examined which tests might best be used to measure active lupus and lupus nephritis. As Dr. Schur notes, “People are looking for better assays or better ways to look at the assays.” But complement and anti-DNA remain on that list. Says Dr. Pisetsky, “We still haven’t really come up with a better test.”

Dr. Schur points out the correlation of anti-DNA with active lupus nephritis somewhat depends on how exactly you measure it. He adds, “A lot of clinicians just assume an anti-DNA is an anti-DNA, but it has been demonstrated since the 1970s and 80s that a lot depends on which assay you use.”

Similarly, Dr. Schur notes that the currently performed tests for C3 and C4 do not correlate as well with lupus nephritis as the CH50 test he used in The New England Journal of Medicine paper. Research into complement activation products—fragments formed upon complement activation—is also ongoing. Some work suggests such products as C4d also may also be used to diagnose active lupus nephritis and potentially help predict disease flares.9

As Dr. Pisetsky notes, “The fact that we are still asking the question says that the original findings reported by Schur still have a lot of resonance in the field, because we are still trying to find a better way of looking at complement and anti-DNA.”

He summarizes what makes the paper stand out, over 50 years later. “The elements are all there: The fact that there are immune complexes; that these antibodies go up and then go down; that DNA comes into the blood at least sometimes in active disease; that immune complexes form; that the presence of complexes is associated with inflammation. I just think it is one of those papers that unites a lot of elements and points in a lot of interesting directions.”

Dr. Pisetsky adds, “Papers like this have a long lifetime. I always say, ‘The paper doesn’t give you the answers; the paper gives you the questions.’ Why do the DNA antibodies go up and down? What accounts for the variable appearance of DNA in the blood? What are the mechanisms by which the inflammation gets under control? Why are these complexes so pathogenic? All those questions are right there.”

Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD, is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine. She is a freelance medical and science writer living in Bloomington, Ind.

References

- Schur PH, Sandson J. Immunologic factors and clinical activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 1968 Mar 7;278(10):533–538.

- Hargraves MM, Richmond H, Morton R. Presentation of two bone marrow elements; the tart cell and the L.E. cell. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1948 Jan 21;23(2):25–28.

- Mackay IR. Travels and travails of autoimmunity: A historical journey from discovery to rediscovery. Autoimmun Rev. 2010 Mar;9(5):A251–258.

- Tan EM, Schur PH, Carr RI, et al. Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and antibodies to DNA in the serum of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1966 Nov;45(11):1732–1740.

- Koffler D, Schur PH, Kunkel HG. Immunological studies concerning the nephritis of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med. 1967 Oct 1;126(4):607–624.

- Townes AS, Stewart Jr CR, Osler AG. Immunologic studies of systemic lupus erythematosus. II. Variations of nucleoprotein-reactive gamma globulin and hemolytic serum complement levels with disease activity. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1963 Apr;112:202–219.

- Yung S, Chan TM. Mechanisms of kidney injury in lupus nephritis—The role of anti-dsDNA antibodies. Front Immunol. 2015 Sep 15;6:475.

- Putterman C, Pisetsky DS, Petri M, et al. The SLE-key test serological signature: New insights into the course of lupus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018 Sep 1;57(9):1632–1640.

- Martin M, Smoląg KI, Björk A, et al. Plasma C4d as marker for lupus nephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017 Dec 6;19(1):266.