As women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) live longer and healthier lives, more and more are asking whether they can or should become pregnant. Forty years ago, a rheumatologist would have been correct to discourage a woman with SLE who wanted to have a child; the rate of pregnancy loss for a woman with SLE was more than 40% at that time. In recent years, however, the success rate of SLE pregnancies has increased significantly. Currently, the risk of pregnancy loss for someone with SLE is roughly equivalent to that of a healthy woman.1 However, pregnancy in a woman with SLE is not always without complication.

Risks to the Fetus and Child

The birth of a healthy full-term baby following an easy pregnancy is the goal of every woman, but it may not be the reality for many women with SLE. Though fewer women with SLE will lose their pregnancy than in previous decades, many are still at increased risk for preterm birth. In general, a third of all SLE pregnancies deliver early – meaning prior to 37 weeks of gestation – and a significant minority will deliver in the even more dangerous period prior to 32 weeks gestation.2 Though most babies born to women with SLE are healthy, neonatal lupus manifesting as congenital heart block can occur in up to 2% of babies exposed to Ro/SSA and/or La/SSB antibodies.3 The immune system of babies born to women with SLE appears to be functionally intact, with few reports of significant infections or lasting immunodeficiency.4 While most children born to women with SLE have normal development and intelligence, there may be a modest increase in the rate of learning disabilities in elementary school–age boys.5 A small proportion of offspring (around 10%) will develop an autoimmune disease at some point in life.6

Risks to the Mother

The risks to the pregnant woman with SLE are low, but present. The maternal mortality rate among women with SLE is 20-fold higher than the maternal mortality for healthy women in the U.S.7 Though this risk may appear high, the absolute risk of death during the year of pregnancy does not appear to be greater than any other year that a woman lives with SLE. In a nationwide study of SLE pregnancies, the maternal mortality rate was 0.325%; the annual mortality rate for a non-pregnant woman with lupus is several times higher – between 0.7% and 2.5% in most studies.8,9 This study also found that increased risks for stroke, deep vein thrombosis, infection, and hematologic abnormalities among women with SLE were higher than in the general population. Up to one quarter of women with SLE will develop preeclampsia (hypertension and proteinuria related to pregnancy). The bulk of the evidence points to a modestly increased risk for SLE activity during pregnancy. Fortunately, severe SLE flares in pregnancy are not common, and the majority of symptoms are related to musculoskeletal and cutaneous disease.

So, how can we optimize the chances for pregnancy success for a woman with SLE? Are there strategies that we can use to decrease her risks? Can we improve her chances of delivering a full-term, healthy baby? Fortunately, I think that we can. Here are some of the steps that we, as rheumatologists, can take to help our patients grow healthy babies.

Step 1: Conceive when Lupus is Quiescent

To give a pregnancy the best chance for success, the woman should have quiet lupus at the time of conception. The importance of lupus activity at the time of conception has been known for years.10 The Hopkins Lupus Cohort offers a clear demonstration of the negative effects of SLE activity at conception. In this cohort of 265 pregnancies, 42% of women with SLE activity in the six months prior to conception suffered a pregnancy loss, compared with 11% who conceived during a period of quiescence.11 Similarly, lupus activity in the first trimester – whether assessed with a physician’s global assessment, thrombocytopenia, or proteinuria – led to a several-fold increase in pregnancy loss over more stable SLE patients.12

Though the timing of any pregnancy can be challenging, it is clearly important in women with SLE. Women with active lupus should be offered contraception in order to avoid the pregnancy tragedies that may result. Because women on cyclophosphamide may still be fertile during therapy, a pregnancy test should be performed prior to each intravenous dosage and contraception should be encouraged. Good contraception options for women with active lupus include progesterone-only pills or the Depo-provera shot, an intrauterine device (IUD), or barrier methods (condoms or a diaphragm). Though estrogen-containing oral contraceptives may be safe for women with mild or inactive lupus, they have not been tested in women with significant disease activity.13,14

It is important to weigh the potential risks of each medication to the developing fetus versus the benefit of each in maintaining low lupus activity prior to and during pregnancy.

Step 2: Continue Some Medications, Discontinue Others

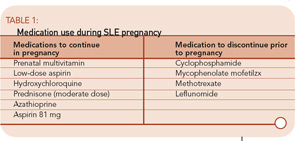

The need to conceive when lupus is quiet brings us to the use of medications to control lupus activity. Discontinuing all medications when a woman is ready to conceive will often prompt an SLE flare, thus endangering her pregnancy. Therefore, it is important to weigh the potential risks of each medication to the developing fetus versus the benefit of each in maintaining low lupus activity prior to and during pregnancy. (See summary in Table 1.)

All women contemplating pregnancy should take a pre-natal multivitamin prior to conception. Women who have taken methotrexate or sulfasalazine may be folate deficient, and therefore in particular need of extra folic acid prior to pregnancy.

Low-dose aspirin has been studied extensively in pregnancy, primarily as a preventive measure against preeclampsia. In a Cochrane Collaboration report of more than 20 such studies, the risk of preeclampsia, preterm birth, and fetal demise were all modestly – but significantly – decreased.15 The Cochrane report recommends that all women at high risk for preeclampsia consider taking a low dose of aspirin throughout pregnancy. Aspirin at this dose has proven safe and does not increase congenital abnormalities in the offspring. In studies of SLE pregnancies, preeclampsia may occur in 10% to 25% of all pregnancies, compared with 5% to 10% of healthy pregnancies.7,16 For this reason, it may be argued that all women with SLE should take a low-dose aspirin throughout pregnancy.

The maintenance of normal blood pressure is important throughout pregnancy. Women with hypertension in the first trimester have a several-fold increased risk for pregnancy loss.12 In the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, this risk was eliminated by the maintenance of normal blood pressure with anti-hypertensive medication. Most obstetricians prefer to avoid ACE inhibitors and diuretics during pregnancy. For this reason, modification of a woman’s anti-hypertensive regimen may be required – preferably prior to conception.

Hydroxychloroquine is considered safe during pregnancy. More than 300 pregnancies in patients on this drug have been reported, with no increased risk for congenital abnormalities identified. Ophthalmologic and cardiac abnormalities have not been identified in offspring after systematic exams.17 Further, in the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, there was an increase in lupus activity during pregnancy among women who discontinued hydroxychloroquine early in pregnancy.18 These women had more arthritis and cutaneous disease and required higher doses of corticosteroids to control their disease during pregnancy. Based on this data, I recommend that all women continue hydroxychloroquine ≤400 mg per day throughout pregnancy.

Azathioprine may be the safest immunosuppressant in pregnancy. There are extensive reports of pregnancies exposed to azathioprine among women with kidney transplantation or inflammatory bowel disease.19 These studies did not find an increased risk for congenital abnormalities among infants exposed in utero to azathioprine. They did find, however, an increased rate of preterm births after azathioprine exposure. It is unclear if this was caused by the drug or the underlying disease it was used to treat.

In the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, 31 pregnancies were exposed to azathioprine.20 There was no increase in the rate of miscarriages for pregnancies exposed to azathioprine in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy. The risk of stillbirth was increased in pregnancies with azathioprine, however this appeared to be related to higher lupus activity among women taking the medication. Among the 18 women who conceived while taking azathioprine, two of the four that developed highly active lupus in pregnancy suffered a loss. Another two of the four that discontinued the drug suffered a loss. The remaining 10 pregnancies in which the woman continued the drug and maintained low activity lupus resulted in live births. I recommend continuing azathioprine during pregnancy if it was required prior to conception to treat SLE. Based on the current evidence, the risk of discontinuation prompting a significant flare may outweigh the toxicity to the fetus.

Corticosteroids can be used in pregnancy when needed, though prophylactic treatment is not recommended. Routine use of corticosteroids may increase the risk for hypertension, diabetes, infection, and preterm birth. Moderate doses of corticosteroids to treat active lupus, however, are well tolerated. Prednisone and prednisolone are metabolized by the placenta, allowing only 10% of the maternal dose to reach the fetus. Fluorinated corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone and betamethasone, are not metabolized and thus easily transfer to the fetus. Therefore, fluorinated steroids can be used to treat the fetus, such as to modify congenital heart block or prior to a preterm delivery, but they should be avoided in routine treatment of lupus during pregnancy. Corticosteroid use in the first trimester has been associated with a three-fold increased risk for cleft lip and palate.21 The absolute risk for this complication is low, occurring in an average of three per 1,000 live births with early corticosteroid exposure. Lip and palate formation are complete by the eighth week of gestation, so steroid use later in pregnancy may not increase this risk.

Medications not considered safe in pregnancy include cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, and leflunomide.19 Each of these drugs has been clearly associated with congenital anomalies, particularly when exposure occurs in the first trimester. If a woman contemplating pregnancy is taking one of these medications, it should be discontinued if possible and replaced with azathioprine, sulfasalazine, or a moderate dose of prednisone. If pregnancy occurs while the patient is taking one of these drugs, close obstetrical follow-up is required. The rate of congenital abnormalities does not dictate routine pregnancy termination, but fetuses should be examined closely for abnormalities via ultrasound. Women on leflunomide should be treated with cholestyramine to eliminate the drug if pregnancy is desired or discovered.

If a woman requires medications to maintain quiet lupus, then medication should be continued in pregnancy. If a woman is on a higher-risk medication, consider switching her to azathioprine prior to pregnancy.

Step 3: Monitor Closely During Pregnancy

Given the risks of pregnancy in women with lupus, it is important for these women to be closely monitoring by a rheumatologist and obstetrician skilled in high-risk pregnancies. From the rheumatologist’s standpoint, SLE can harm a pregnancy through three primary routes:

- SLE activity;

- Ro(SSA) and La(SSB) antibodies causing neonatal SLE; and

- Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).

SLE Activity in Pregnancy

The rheumatologist’s primary role is to identify SLE activity during pregnancy. This can be a challenge, as many symptoms of pregnancy can mimic SLE. Many pregnant women will suffer from fatigue and lower extremity and hand swelling. Chloasma, or the “mask of pregnancy,” can be mistaken for a malar rash as it manifests with a photosensitive hyperpigmented discoloration over the cheeks, forehead, and nose.

Many laboratory values change during pregnancy, which may make discerning SLE activity more challenging. Up to 8% of healthy women will have mild thrombocytopenia during pregnancy, though significant declines in the platelet count are more likely related to SLE or APS. During pregnancy, a woman’s blood volume increases 50%. This leads to mild anemia in many women. It also leads to increased renal blood flow and a drop in the serum creatinine. Due to this increased renal function, proteinuria may increase in women with prior glomerular injury. A modest proteinuria increase early in pregnancy in a woman with prior lupus nephritis can be followed expectantly, particularly if the urine sediment is not active, but increases in proteinuria greater than 50% or 1 gram may be indicative of active renal disease.

The total complement level may increase up to 50% in some women during pregnancy. In the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, however, half of all pregnancies had hypocomplementemia. Low complement on its own was not associated with poor pregnancy outcomes. However, women with low complement and active SLE had particularly poor outcomes: This group had a four-fold increase in pregnancy loss and a four-fold decrease in term births compared with all other SLE pregnancies.22

I recommend that pregnant women with SLE be seen monthly by their rheumatologist to assess for SLE activity. Despite many obstetricians’ skill in managing their patients’ medical problems, few are comfortable assessing and treating SLE activity. If a woman has increasing SLE activity during pregnancy, she should be treated promptly. Unfortunately, no studies of SLE treatment can indicate best how to treat an SLE flare in pregnancy. I usually use moderate doses of prednisone, or an in-office intramuscular injection of triamcinolone, to treat mild to moderate flares. For more severe flares, higher doses of corticosteroids are appropriate. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) is considered safe in pregnancy and may be a good alternative to immunosuppressives for severe lupus activity in pregnancy.23

Currently, the risk of pregnancy loss for someone with SLE is roughly equivalent to that of a healthy woman. However, pregnancy in a woman with SLE is not always without complication.

Preeclampsia

The distinction between preeclampsia and lupus nephritis can be particularly difficult to discern. Preeclampsia is defined as hypertension (≥140/90) and proteinuria (≥300 mg per 24 hours) that occurs after the 20th week of gestation. Severe preeclampsia is defined by higher blood pressure and proteinuria levels and is accompanied by other organ damage, including elevated liver tests, thrombocytopenia, and mental status changes. Eclampsia is the addition of grand mal seizures. HELLP syndrome is a severe form of preeclampsia distinguished by hemolysis, elevated liver tests, and low platelets. As the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia can be similar to a severe SLE flare, it can be difficult – if not impossible – to distinguish between the two. The distinction is important, however, because treatment is different: For severe preeclampsia, it is delivery. For SLE, it is immunosuppression. In some cases, treatment for both may be prudent.

Though no single test will perfectly distinguish between preeclampsia and SLE, there are several approaches that may help.

- Low complement and rising dsDNA titers are more commonly seen with active SLE than preeclampsia;

- Other signs of active SLE, such as inflamed joints and flaring SLE cutaneous reactions, may signify an SLE flare; and

- Though both present with proteinuria, the urine sediment is usually benign in preeclampsia, whereas SLE nephritis will often have an active sediment with red blood cells, white blood cells, and casts.

Neonatal Lupus

An estimated 10% of babies born to women with Ro(SSA) and/or La(SSB) antibodies have signs of neonatal lupus. The majority of these babies will have a photosensitive rash (similar in appearance to subacute cutaneous lupus) prior to six months of age. Fortunately, the rash does not leave a scar and will resolve as the Ro and La antibodies are cleared by the infant. Up to 2% of babies, however, will develop congenital heart block as a result of in utero exposure to the pathogenic antibodies. No cases of complete heart block have been reversed with therapy. However, there are case reports of fetuses with first- or second-degree heart block reversing after therapy with dexamethasone.3 Therefore, frequent screening between the 16th and 28th weeks of gestation with a fetal echocardiogram to measure the PR interval is recommended. Any increase in the PR interval should prompt therapy with dexamethasone 4 mg each day.

Antiphospholipid Syndrome

APS is associated with a high risk for pregnancy loss and may increase the risk for preeclampsia and placental insufficiency. For a woman with prior pregnancy losses due to APS, therapy with low–molecular weight heparin and aspirin during pregnancy may significantly improve her chances to deliver a live baby. For women with the antibodies of the syndrome (anticardiolipin or anti-b2-glycoprotein1 antibodies, or the lupus anticoagulant) but no prior pregnancy losses or thromboses, the best course of treatment is more difficult to discern. Though definitive data are lacking, I recommend treating these women with low-dose aspirin throughout pregnancy.

Summary

In the 21st century, the majority of pregnancies in women with SLE will be successful, resulting in a well baby and a healthy mother. Planning prior to conception – in particular, timing the pregnancy to coincide with a period of SLE quiescence and modifying medications – can increase the chances for a happy outcome. Careful monitoring by a rheumatologist for SLE activity and a high-risk obstetrician for pregnancy and fetal troubles will provide the best opportunity for success. New, targeted therapies for SLE appear to be on the horizon. Systematic evaluation of the safety and efficacy of these drugs in pregnancy may lead to further pregnancy success in young women with SLE.

Dr. Clowse is assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology and Immunology, director of the Duke Autoimmunity in Pregnancy Clinic and Registry, and co-director of the Duke Lupus Clinic at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C.

References

- Clark CA, Spitzer KA, Laskin CA. Decrease in pregnancy loss rates in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus over a 40-year period. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(9):1709-1712.

- Clark CA, Spitzer KA, Nadler JN, Laskin CA. Preterm deliveries in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(10):2127-2132.

- Buyon JP, Clancy RM. Neonatal lupus: review of proposed pathogenesis and clinical data from the US-based Research Registry for Neonatal Lupus. Autoimmunity. 2003;36(1):41-50.

- Parke A. Drug exposure, pregnancy outcome and fetal and childhood development occurring in the offspring of mothers with systemic lupus erythematosus and other chronic autoimmune diseases. Lupus. 2006; 15(11):808-813.

- Ross G, Sammaritano L, Nass R, Lockshin M. Effects of mothers’ autoimmune disease during pregnancy on learning disabilities and hand preference in their children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(4):397-402.

- Priori R, Medda E, Conti F, et al. Familial autoimmunity as a risk factor for systemic lupus erythematosus and vice versa: a case-control study. Lupus. 2003; 12(10):735-740.

- Clowse MEB, Jamison MG, Myers E, James AH. National study of medical complications in SLE pregnancies. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9 (suppl.)):S263.

- Bernatsky S, Boivin JF, Joseph L, et al. Mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2006; 54(8):2550-2557.

- Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, et al. Morbidity and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus during a 10-year period: a comparison of early and late manifestations in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82(5): 299-308.

- Urowitz MB, Gladman DD, Farewell VT, Stewart J, McDonald J. Lupus and pregnancy studies. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(10):1392-1397.

- Clowse ME, Magder LS, Witter F, Petri M. The impact of increased lupus activity on obstetric outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(2):514-521.

- Clowse ME, Magder LS, Witter F, Petri M. Early risk factors for pregnancy loss in lupus. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(2 Pt. 1):293-299.

- Petri M, et al. Combined oral contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(24):2550-2558.

- Sanchez-Guerrero J, et al. A trial of contraceptive methods in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(24):2539-2549.

- Ruano R, Fontes RS, Zugaib M. Prevention of preeclampsia with low-dose aspirin – a systematic review and meta-analysis of the main randomized controlled trials. Clinics. 2005;60(5):407-414.

- Chakravarty EF, et al. Factors that predict prematurity and preeclampsia in pregnancies that are complicated by systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(6):1897-1904.

- Costedoat-Chalumeau N, et al. Safety of hydroxychloroquine in pregnant patients with connective tissue diseases: a study of one hundred thirty-three cases compared with a control group. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(11):3207-3211.

- Clowse ME, et al. Hydroxychloroquine in lupus pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(11):3640-3647.

- Ostensen M, et al. Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs and reproduction. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(3):209.

- Clowse MEB, Magder LS, Witter F, Petri M. Azathioprine use in lupus pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum. 2005; 52(9 (suppl.)).

- Pradat P, et al. First trimester exposure to corticosteroids and oral clefts. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2003;67(12):968-970.

- Clowse MEB, Magder LS, Petri M. Complement and double-stranded DNA antibodies predict pregnancy outcomes in lupus patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2004; 50(9(suppl.)):S408.

- Gordon C, Kilby MD. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in pregnancy in systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Lupus. 1998;7(7):429-433.