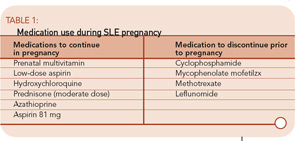

If a woman requires medications to maintain quiet lupus, then medication should be continued in pregnancy. If a woman is on a higher-risk medication, consider switching her to azathioprine prior to pregnancy.

Step 3: Monitor Closely During Pregnancy

Given the risks of pregnancy in women with lupus, it is important for these women to be closely monitoring by a rheumatologist and obstetrician skilled in high-risk pregnancies. From the rheumatologist’s standpoint, SLE can harm a pregnancy through three primary routes:

- SLE activity;

- Ro(SSA) and La(SSB) antibodies causing neonatal SLE; and

- Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).

SLE Activity in Pregnancy

The rheumatologist’s primary role is to identify SLE activity during pregnancy. This can be a challenge, as many symptoms of pregnancy can mimic SLE. Many pregnant women will suffer from fatigue and lower extremity and hand swelling. Chloasma, or the “mask of pregnancy,” can be mistaken for a malar rash as it manifests with a photosensitive hyperpigmented discoloration over the cheeks, forehead, and nose.

Many laboratory values change during pregnancy, which may make discerning SLE activity more challenging. Up to 8% of healthy women will have mild thrombocytopenia during pregnancy, though significant declines in the platelet count are more likely related to SLE or APS. During pregnancy, a woman’s blood volume increases 50%. This leads to mild anemia in many women. It also leads to increased renal blood flow and a drop in the serum creatinine. Due to this increased renal function, proteinuria may increase in women with prior glomerular injury. A modest proteinuria increase early in pregnancy in a woman with prior lupus nephritis can be followed expectantly, particularly if the urine sediment is not active, but increases in proteinuria greater than 50% or 1 gram may be indicative of active renal disease.

The total complement level may increase up to 50% in some women during pregnancy. In the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, however, half of all pregnancies had hypocomplementemia. Low complement on its own was not associated with poor pregnancy outcomes. However, women with low complement and active SLE had particularly poor outcomes: This group had a four-fold increase in pregnancy loss and a four-fold decrease in term births compared with all other SLE pregnancies.22

I recommend that pregnant women with SLE be seen monthly by their rheumatologist to assess for SLE activity. Despite many obstetricians’ skill in managing their patients’ medical problems, few are comfortable assessing and treating SLE activity. If a woman has increasing SLE activity during pregnancy, she should be treated promptly. Unfortunately, no studies of SLE treatment can indicate best how to treat an SLE flare in pregnancy. I usually use moderate doses of prednisone, or an in-office intramuscular injection of triamcinolone, to treat mild to moderate flares. For more severe flares, higher doses of corticosteroids are appropriate. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) is considered safe in pregnancy and may be a good alternative to immunosuppressives for severe lupus activity in pregnancy.23

Currently, the risk of pregnancy loss for someone with SLE is roughly equivalent to that of a healthy woman. However, pregnancy in a woman with SLE is not always without complication.

Preeclampsia

The distinction between preeclampsia and lupus nephritis can be particularly difficult to discern. Preeclampsia is defined as hypertension (≥140/90) and proteinuria (≥300 mg per 24 hours) that occurs after the 20th week of gestation. Severe preeclampsia is defined by higher blood pressure and proteinuria levels and is accompanied by other organ damage, including elevated liver tests, thrombocytopenia, and mental status changes. Eclampsia is the addition of grand mal seizures. HELLP syndrome is a severe form of preeclampsia distinguished by hemolysis, elevated liver tests, and low platelets. As the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia can be similar to a severe SLE flare, it can be difficult – if not impossible – to distinguish between the two. The distinction is important, however, because treatment is different: For severe preeclampsia, it is delivery. For SLE, it is immunosuppression. In some cases, treatment for both may be prudent.