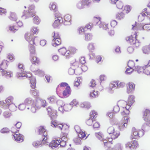

Eosinophilic fasciitis generally presents with the acute onset of edema followed by progressive skin induration in the setting of hypergammaglobulinemia, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and peripheral eosinophilia in 63–93% of patients.1,2 Skin involvement is typically limited to 20.1% of total body surface area and most commonly involves the extremities symmetrically.1,3

The condition was first described by Lawrence E. Shulman, MD, PhD, in 1974, but despite being a known entity for almost 50 years, no generally accepted diagnostic criteria exist today. The current gold standard for diagnosis remains a full-thickness skin biopsy.4

In one study, 79% of patients with eosinophilic fasciitis were found to be misdiagnosed, most commonly with systemic sclerosis.2 This mistake is likely due to the fact that 30–50% of patients with eosinophilic fasciitis have concomitant morphea plaques.1,2 However, eosinophilic fasciitis can be distinguished from scleroderma largely by a lack of Raynaud’s phenomenon, normal nailfold capillaroscopy and the absence of visceral organ involvement.1

We present the case of a middle-aged woman who developed diffuse, pansclerotic morphea. Her condition was initially diagnosed as scleromyxedema based on skin biopsy, and she was treated unsuccessfully with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) until a full-thickness skin biopsy 10 months later demonstrated bands of fibrosis consistent with eosinophilic fasciitis.

Case Summary

A 55-year-old woman presented at our facility with complaints of shortness of breath and swelling of her face, throat, hands and feet. Her past medical history included ulcerative colitis with no flare despite a decade off of all medications. She had hypertension and hypothyroidism, which were well controlled on levothyroxine. The surgical and family history were non-contributory. Her social history was significant for years of exposure to a wood-stripping agent.

The patient believed her illness had begun eight months earlier when she first presented to her primary care provider with several, non-painful, enlarged cervical lymph nodes, odynophagia, fatigue and, later, generalized body swelling.

The outpatient workup was unrevealing, and before a lymph node biopsy could be performed, repeat imaging demonstrated resolution of the patient’s lymphadenopathy. During the primary care workup, she was treated with diuretics, as well as prednisone, without symptomatic improvement, and she had stopped these medications prior to presentation at our facility.

Figure 1. Evidence of the patient’s small oral aperture at the time of presentation.

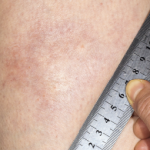

Figure 2. The prayer sign, which is rarely seen in patients suffering from eosinophilic fasciitis.