Eosinophilic fasciitis generally presents with the acute onset of edema followed by progressive skin induration in the setting of hypergammaglobulinemia, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and peripheral eosinophilia in 63–93% of patients.1,2 Skin involvement is typically limited to 20.1% of total body surface area and most commonly involves the extremities symmetrically.1,3

The condition was first described by Lawrence E. Shulman, MD, PhD, in 1974, but despite being a known entity for almost 50 years, no generally accepted diagnostic criteria exist today. The current gold standard for diagnosis remains a full-thickness skin biopsy.4

In one study, 79% of patients with eosinophilic fasciitis were found to be misdiagnosed, most commonly with systemic sclerosis.2 This mistake is likely due to the fact that 30–50% of patients with eosinophilic fasciitis have concomitant morphea plaques.1,2 However, eosinophilic fasciitis can be distinguished from scleroderma largely by a lack of Raynaud’s phenomenon, normal nailfold capillaroscopy and the absence of visceral organ involvement.1

We present the case of a middle-aged woman who developed diffuse, pansclerotic morphea. Her condition was initially diagnosed as scleromyxedema based on skin biopsy, and she was treated unsuccessfully with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) until a full-thickness skin biopsy 10 months later demonstrated bands of fibrosis consistent with eosinophilic fasciitis.

Case Summary

A 55-year-old woman presented at our facility with complaints of shortness of breath and swelling of her face, throat, hands and feet. Her past medical history included ulcerative colitis with no flare despite a decade off of all medications. She had hypertension and hypothyroidism, which were well controlled on levothyroxine. The surgical and family history were non-contributory. Her social history was significant for years of exposure to a wood-stripping agent.

The patient believed her illness had begun eight months earlier when she first presented to her primary care provider with several, non-painful, enlarged cervical lymph nodes, odynophagia, fatigue and, later, generalized body swelling.

The outpatient workup was unrevealing, and before a lymph node biopsy could be performed, repeat imaging demonstrated resolution of the patient’s lymphadenopathy. During the primary care workup, she was treated with diuretics, as well as prednisone, without symptomatic improvement, and she had stopped these medications prior to presentation at our facility.

Figure 1. Evidence of the patient’s small oral aperture at the time of presentation.

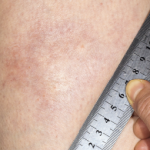

Figure 2. The prayer sign, which is rarely seen in patients suffering from eosinophilic fasciitis.

Figure 3. The skin of the patient’s lower extremities was shiny, thickened and hairless.

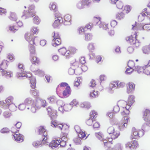

The labs at the time were significant for an albumin of 2.1 gm/dL, a thyroid-stimulating hormone of 1.92 mIU/mL, a 24-hour urine protein of <0.14 gm/24h, a faint IgG kappa restriction (kappa free light chains 3.45 mg/dL with kappa lambda free light chain ratio 1.96), and a white blood cell count of 7.9 x 103 mcL with 21.9% eosinophils. An endoscopy and a colonoscopy were unremarkable; biopsies showed non-specific duodenitis and gastritis. Bone marrow biopsy was normal. Ultimately, she was referred to rheumatology for further workup.

On presentation at the rheumatology clinic, she complained of new symptoms, including jaw locking, hair loss (including loss of her pubic hair), hand swelling, 40 minutes of morning stiffness, fevers, chills and stocking distribution paresthesias.

The physical exam revealed a sallow-complexioned female with temporal wasting bilaterally, a small, tight oral aperture, complete hair loss on her extremities, normal nailfold capillaries, no telangiectasias, no digital ulcers and skin thickening on her face, neck, upper back, arms, hands, legs and feet (see Figures 1–3, below). A joint exam was significant for her inability to abduct her shoulders beyond 90º and bilateral flexion contractures of her elbows. No synovitis was noted.

Laboratory results for creatinine kinase, anti-nuclear antibody, complement, extractable nuclear antigens, vascular endothelial growth factor and RNA polymerase III were all normal, but her C-reactive protein and sedimentation rate peaked at 66 mg/L and 42 mm/hr, respectively. Further imaging included computed tomography of her chest, abdomen and pelvis, which revealed no evidence of malignancy, as well as a skeletal survey that was negative for any osteolytic bone lesions. Electromyography showed diffuse myopathic changes, proximally and distally.

A skin biopsy revealed increased dermal fibroblasts, mucin with hyalinization and a negative congo red stain that was interpreted as diagnostic of scleromyxedema. Treatment with IVIG 2 gm/kg every four weeks was initiated, with initial improvement in her subjective skin thickness.

Approximately six months later, she sought a second opinion at Johns Hopkins when her symptoms worsened. Per their recommendation, forearm magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a bright T2 signal suggestive of fasciitis, and a full-thickness skin biopsy showed bands of fibrosis and hyalinization consistent with eosinophilic fasciitis. Following this biopsy she was started on 60 mg of prednisone, as well as 720 mg of mycophenolate sodium, twice a day.

Unfortunately, she continues to suffer from neuropathic pain and skin thickening.

Eosinophilic fasciitis can be distinguished from scleroderma largely by a lack of Raynaud’s phenomenon, normal nailfold capillaroscopy & the absence of visceral organ involvement.

Discussion

Currently in the literature, several case reports describe patients with atypical presentations of eosinophilic fasciitis involving the face and hands, but we believe our case is the first describing a patient presenting with diffuse, pansclerotic, scleroderma-like skin involvement.5

Acknowledging that a wide diversity of location and degree of skin involvement beyond the typically indurated extremities exists is especially relevant considering the suggestion that joint contractures are the main morbidity associated with eosinophilic fasciitis. Contractures occur in 76% of untreated patients.2,6

Our patient was not referred to a rheumatologist until about one year into her illness and had a diagnostic delay of 23 months. A delay of just six months has been significantly associated with a 14.7 times greater risk of poor treatment response.2 Also, both trunk involvement and concurrent morphea are associated with more severe manifestations of disease. Patients suffering from morphea have a 1.9-fold greater risk of corticosteroid resistance and are three times as likely to require additional immunosuppressive medications.2

Even further striking is the suggestion that the presence of morphea alone may represent a subset of eosinophilic fasciitis patients who are more likely to suffer from residual damage regardless of a diagnostic delay.6 This underlines the importance of having a high index of suspicion for eosinophilic fasciitis in patients presenting with morphea and obtaining full-thickness biopsies when eosinophilic fasciitis is on the differential diagnosis.

Conclusion

Eosinophilic fasciitis is a relatively rare diagnosis with a presentation that is increasingly recognized to be diverse, but as of yet has no codified diagnostic criteria.3 This combination makes its diagnosis particularly challenging, especially in the face of a presentation—such as in our patient—of an unusual degree of skin involvement, which makes it easy to mistake eosinophilic fasciitis for an alternative scleroderma mimic, like scleromyxedema.2

Julia Munchel, MD, is a third-year postgraduate, studying internal medicine at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

Julia Munchel, MD, is a third-year postgraduate, studying internal medicine at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H.

William Monaco, MD, works as a rheumatologist at Maine General Medical Center in Augusta.

William Monaco, MD, works as a rheumatologist at Maine General Medical Center in Augusta.

References

- Lakhanpal S, Ginsburg WW, Michet CJ, et al. Eosinophilic fasciitis: Clinical spectrum and therapeutic response in 52 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1988 May;17(4):221–231.

- Mazori DR, Femia AN, Vleugels RA. Eosinophilic fasciitis: An updated review on diagnosis and treatment. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017 Nov 4;19(12):74.

- Bischoff L, Derk CT. Eosinophilic fasciitis: Demographics, disease pattern and response to treatment: Report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008 Jan;

47(1):29–35. - Morgan ND, Hummers LK. Scleroderma mimickers. Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol. 2016 Mar;2(1):69–84.

- Pardos-Gea J. Positive prayer sign in eosinophilic fasciitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017 Apr 1;56(4):628.

- Suzuki S, Noda K, Ohira Y, et al. Finger stiffness or edema as presenting symptoms of eosinophilic fasciitis. Rheumatol Int. 2015 Oct;35(10):1769–1772.