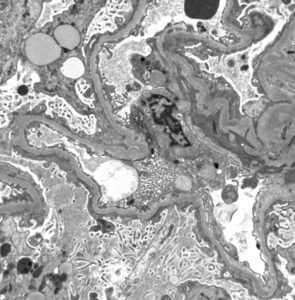

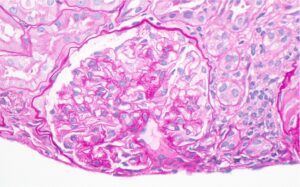

Figure 1: Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain with normal appearing glomeruli or with the minimal change. (Click to enlarge.)

Kidney involvement is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Collectively termed lupus nephritis, SLE with kidney involvement comes in many subtypes. The current classification by the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS), however, does not include lupus podocytopathy, which, through various clinical and epidemiologic studies, has recently been recognized as a distinct subtype of lupus nephritis.1

Lupus podocytopathy is defined clinically as nephrotic-range proteinuria and histology showing normal glomeruli or only mild glomerular mesangial proliferation.2 Studies have shown that 0.6–1.5% of all lupus nephritis biopsies reveal lupus podocytopathy.1,3

In 2002, Dube et al. and Hertig et al. described 18 patients with SLE and nephrotic syndrome with renal biopsy showing minimal change disease (MCD) or focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) changes.4,5 Later, in 2016, Hu et al. described 50 patients with lupus podocytopathy with improved understanding of the condition as a distinct entity.2 One of the characteristic features of lupus podocytopathy is responsiveness to glucocorticoid therapy. Despite the growing awareness of lupus podocytopathy, high-quality data on the disease course and management of lupus podocytopathy is lacking, particularly in cases of treatment resistance. We present a case of glucocorticoid refractory lupuspodocytopathy with relapse.

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old woman with SLE presented with generalized edema and fatigue for two weeks, associated with exertional shortness of breath and foamy urine. Manifestations of her SLE included inflammatory arthritis and leukopenia; her antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer was positive at 1:320, along with antidouble-stranded DNA (dsDNA) positivity (46 IU/mL; normal <9 IU/mL) and SSA positivity (8 AI [autobody index]; normal <0.9 AI). She had been treated with 5 mg/kg of hydroxychloroquine monotherapy for the past three years.

Her physical examination was remarkable for severe generalized edema. Laboratory data revealed anemia, with hemoglobin of 9.2 g/dL (normal range 11.7–15.5 g/dL); leukopenia, with white cell count of 1.52 k/uL (normal 3.8–10.8 k/uL); elevated creatinine at 2.5 mg/dL above her baseline of 0.65 mg/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 24 mL/min/1.73 m2; elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 69 mm/hr (normal <20 mm/hr); and hypoalbuminemia of 0.9 g/dL (normal 3.6–5.1 g/dL). Urinalysis showed hematuria (red blood cell [RBC] count of >180/high power field [HPF]) and nephrotic range proteinuria, with a urine protein to creatinine ratio (UPCR) of 12,888 mg/g.

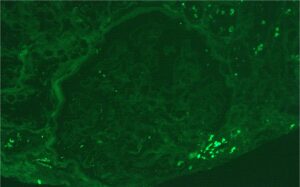

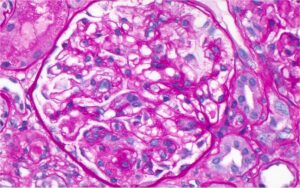

A renal biopsy was performed (see Figs. 1–3) and showed class 1 or class 2 lupus nephritis with diffuse podocyte foot process effacement and minimal mesangial immune complex deposition, consistent with lupus podocytopathy. replacement therapy was initiated in the hospital, and she remained dialysis dependent for approximately six weeks. A few days after dialysis was initiated, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) was started to induce remission of her lupus podocytopathy. Later during her clinical course, she experienced gastrointestinal intolerance, so she was switched from MMF to mycophenolic acid (MPA). She was continued on hydroxychloroquine at a renally adjusted dose of 200 mg once daily.

Two months after her initial presentation, her proteinuria improved to a urine protein to creatinine ratio of 393 mg/g, and her renal function improved, with a creatinine level of 1.04 mg/dL and an eGFR of 52 mL/min/1.73 m2. A glucocorticoid taper was continued.

Four months after her initial diagnosis of lupus podocytopathy, while she was taking 30 mg of prednisone daily, hydroxychloroquine and MPA, she relapsed, experiencing worsening edema with a urine protein to creatinine ratio of 15,111 mg/g and deteriorating renal function, with a creatinine level of 2.8 mg/dL and eGFR of 22 mL/min/1.73 m2. Her prednisone dose was increased back to 60 mg per day and voclosporin, a novel calcineurin inhibitor (CNI), was added, renally dose adjusted to 7.9 mg twice a day.

About a month following this relapse (five months after diagnosis), MPA was discontinued due to worsening gastrointestinal side effects and intravenous cyclophosphamide was initiated in an attempt to induce remission. Her renal function continued to deteriorate, with peak creatinine of 4.96 mg/dL, eGFR 9 mL/min/1.73 m2 and a urine protein to creatinine ratio of 29,569 mg/g. Diureticrefractory edema and symptomatic uremia necessitated re-initiation of renal replacement therapy.

A repeat renal biopsy (see Figure 4) showed focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), diffuse podocyte foot process effacement and low intensity mesangial immune deposits consistent with mesangial lupus nephritis (class 1) and lupus podocytopathy. She continued a regimen of monthly, intravenous cyclophosphamide, hydroxychloroquine, low-dose voclosporin and slow taper of prednisone. After completion of six monthly doses of intravenous cyclophosphamide, the patient’s renal function improved to an eGFR of 35 mL/min/1.73 m2, creatinine of 1.5 mg/dL and a 24-hour proteinuria of 480 mg. Thus, dialysis was discontinued. The prednisone dose was tapered slowly to 6 mg daily, with plans to continue tapering at the last follow up, which was 16 months following the initial diagnosis of lupus podocytopathy. Rituximab maintenance therapy was initiated at two doses of 1 g each at two-week intervals, with the intention of continuing her treatment with 1 g every six months thereafter.

After the first dose of rituximab, the patient was noted to have a stable renal response, with an eGFR of 44 mL/min/1.73 m2, creatinine of 1.30 mg/dL and urine protein to creatinine ratio of 469 mg/g.

Discussion

Lupus podocytopathy clinically presents as nephrotic range proteinuria, which correlates with the extent of foot process effacement.3,6 The diagnostic criteria proposed by Hu et al. are:2

- Clinical presentation: nephrotic range proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia and edema; and

- Histologic picture:

- minimal change disease (MCD), mesangial proliferative change or focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS); immunofluorescence showing minimal immunoglobulin and complement deposition or no immune complex deposition in mesangial areas; and absence of subepithelial and subendothelial immune complex deposition;

- presence of diffuse podocyte foot process effacement (FPE) on electron microscopy, typically >70%.

Additionally, features of endocapillary proliferation, crescents and necrosis are absent in lupus podocytopathy.3 Podocyte injury by other causes, such as thrombotic microangiopathy, should be excluded.3,7 Our patient met the above clinical and histological criteria for lupus podocytopathy.

Based on histopathology, lupus podocytopathy can be divided into three subtypes: 1) MCD (normal light microscopy without mesangial proliferation); 2) FSGS; and 3) mesangioproliferative lupus nephritis (class 1 or 2 lupus nephritis changes with podocytopathy).1 The mesangial form is the most common form of lupus podocytopathy.1 The FSGS subtype is associated with acute kidney injury and tubulointerstitial involvement, and is further classified as not otherwise specified (NOS), perihilar, cellular, tip or collapsing variant, of which the collapsing variant has the worst prognosis.1,3,8

Although the pathogenesis of lupus podocytopathy is not well understood, direct podocyte injury mediated by cytokines, lymphokines or T cell dysfunction, rather than immune complex deposition is thought to be the driving force.3,9,10 In general, lupus podocytopathy is considered a glucocorticoid-responsive entity. Following the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO) treatment guidelines for MCD, lupus podocytopathy can be treated with 1 mg/kg of glucocorticoids, tapered over six months after achieving complete remission (defined as reduction of proteinuria to <0.3 g/day, stable serum creatinine and serum albumin of >3.5 g/dL) or based on clinical response.11,12

A high risk of relapse has been reported with glucocorticoid monotherapy.2 In Hu et al.’s study, there were no differences in response for induction with glucocorticoids alone vs. glucocorticoids with immunosuppression. But more than half the patients with lupus podocytopathy who were on maintenance with glucocorticoids alone relapsed.2

The FSGS subtype carries the worst prognosis, is less responsive to glucocorticoids, and has higher rates of relapse and subsequent progression to end-stage renal disease.3 As in our patient’s case, the recommendations is to treat the FSGS subtype of lupus podocytopathy more aggressively, with glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive agents for both induction and maintenance therapy.

Immunomodulatory agents reported in observational studies of lupus podocytopathy include MMF, calcineurin inhibitors, cyclophosphamide and rituximab.13 Mycophenolate mofetil and cyclophosphamide are two commonly used treatments for lupus nephritis, but their use can be limited by gastrointestinal toxicity and myelosuppression, respectively. Calcineurin inhibitors stabilize the podocyte cytoarchitecture, in addition to their role in T cell inhibition, and are shown to have better remission rates in lupus podocytopathy.14 When used, consideration of renal dose adjustment is required, and caution must be taken in those with an eGFR of <45 mL/min. Rituximab has also been shown to have protective benefits on the podocyte cytoarchitecture and improves cell adhesion, in addition to its B cell depleting effect.15

Lupus podocytopathy can present with or without extra-renal manifestations of SLE. In a study involving 125 renal biopsies, 31 of which were characterized as a podocyte group with >50% FPE and nephrotic syndrome, less extra-renal involvement was reported.16 However, in other studies, extrarenal SLE manifestations not limited to malar rash, oral sores, arthritis and cytopenia were reported.3 Our patient did not have any extra-renal manifestations.

According to the current classification criteria of lupus nephritis, some lupus podocytopathy cases may be classified as lupus nephritis class 1 or class 2, due to the presence of mesangial deposition and mesangial proliferation, and we might not proceed with aggressive immunosuppressive treatment. The clinical picture may mimic class 5 membranous lupus nephritis due to significant proteinuria. Hence, multidisciplinary collaboration with pathology and nephrology is essential in recognizing and managing this entity.

Conclusion

Lupus podocytopathy should be suspected when patients with SLE present with nephrotic range proteinuria, absent subendothelial or subepithelial immune deposits on renal biopsy and diffuse foot process effacement. This can histologically present as class 1 or class 2 lupus nephritis, or clinically as class 5 lupus nephritis. It is important to recognize lupus podocytopathy to select the most appropriate treatment regimen given the high risk of relapse.

Despite the importance of establishing the diagnosis of lupus podocytopathy, there remain significant gaps in the literature, especially in describing the efficacy of treatment regimens.

Vineetha Philip, MD, MPH, is a second-year fellow in the adult rheumatology program at Houston Methodist Hospital.

Vineetha Philip, MD, MPH, is a second-year fellow in the adult rheumatology program at Houston Methodist Hospital.

Myriam Guevara, MD, is the program director for the adult rheumatology fellowship program at Houston Methodist Hospital.

Myriam Guevara, MD, is the program director for the adult rheumatology fellowship program at Houston Methodist Hospital.

Angelina Edwards, MD, is the program director for the nephrology fellowship program at Houston Methodist Hospital.

Angelina Edwards, MD, is the program director for the nephrology fellowship program at Houston Methodist Hospital.

Ziad M. El-Zataari, MD, is an assistant professor of clinical pathology and laboratory medicine at Houston Methodist Hospital and practices as an academic surgical pathologist with expertise in medical renal pathology.

Ziad M. El-Zataari, MD, is an assistant professor of clinical pathology and laboratory medicine at Houston Methodist Hospital and practices as an academic surgical pathologist with expertise in medical renal pathology.

References

- Chen D, Hu W. Lupus podocytopathy: A distinct entity of lupus nephritis. J Nephrol. 2018 Oct;31(5):629–634.

- Hu W, Chen Y, Wang S, et al. Clinical-morphological features and outcomes of lupus podocytopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 Apr;11(4):585–592.

- Oliva-Damaso N, Payan J, Oliva-Damaso E, et al. Lupus podocytopathy: An overview. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019 Sep;26(5):369–375.

- Dube GK, Markowitz GS, Radhakrishnan J, et al. Minimal change disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Nephrol. 2002 Feb;57(2):120–126.

- Hertig A, Droz D, Lesavre P, et al. SLE and idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: Coincidence or not? Am J Kidney Dis. 2002 Dec;40(6):1179–1184.

- Han TS, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ. Association of glomerular podocytopathy and nephrotic proteinuria in mesangial lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2006;15(2):71–75.

- Almaani S, Meara A, Rovin BH. Update on lupus nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(5):825–835.

- Bomback AS, Markowitz GS. Lupus podocytopathy: A distinct entity. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 Apr;11(4):547–548.

- Yu F, Haas M, Glassock R, et al. Redefining lupus nephritis: Clinical implications of pathophysiologic subtypes. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017 Aug;13(8):483–495.

- Trivedi S, Zeier M, Reiser J. Role of podocytes in lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009 Dec;24(12):3607–3612.

- Navarro D, Ferreira AC, Viana H, et al. Morphological indexes: Can they predict lupus nephritis outcomes? A retrospective study. Acta Med Port. 2019 Oct;32(10):635–640.

- Rovin BH, Adler SG, Barratt J, et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2021 guideline for the management of glomerular diseases. Kidney Int. 2021 Oct;100(4):753–779.

- Bomback AS. Nonproliferative forms of lupus nephritis: An overview. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2018 Nov;44(4):561–569.

- Wang Y, Yu F, Song D, et al. Podocyte involvement in lupus nephritis based on the 2003 ISN/RPS system: A large cohort study from a single centre. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(7): 1235–1244.

- Jeruschke S, Alex D, Hoyer PF, Weber S. Protective effects of rituximab on puromycin-induced apoptosis, loss of adhesion and cytoskeletal alterations in human podocytes. Sci Rep. 2022 Jul; 12(1):12297.

- Wang SF, Chen YH, Chen DQ, et al. Mesangial proliferative lupus nephritis with podocytopathy: A special entity of lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2018 Feb; 27(2):303–311.