FIGURE 1: The patient presented with an erythematous, tender, nodular rash overlying both of his lower extremities and lower abdomen. (Click to enlarge.)

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a necrotizing vasculitis, predominantly involving medium-sized arteries, that causes systemic disease, and, less commonly, cutaneous-limited disease. The population prevalence for PAN ranges from 2 to 33 per million.1-3 Estimates vary due to the increased recognition and classification of other forms of vasculitides over time and variation in the regional prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection, a disease that is closely associated with PAN. Cutaneous PAN accounts for approximately 4% of all cases of PAN.4

Here, we present a case of cutaneous PAN with antecedent group A Streptococcal infection, treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), colchicine, prednisone and antibiotics.

Case Description

A 22-year-old man with a past medical history of gastric sleeve surgery and active tobacco use presented with a painful rash and polyarthralgia. His rash had started four weeks before on the sole of his left foot and spread in an ascending manner, involving both lower extremities, his groin region and abdomen. He developed swelling and pain in his left knee two weeks before and pain in his bilateral elbows two days before presentation. He was febrile up to 102.8ºF (39.3ºC) the first night of his hospitalization, although the patient did not mention having a fever while at home.

The patient stated that a punch biopsy of his left calf rash had been performed by a community dermatologist a few days earlier. The tissue sample contained a muscular blood vessel associated with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate including neutrophils and eosinophils; fibrinoid and basophilic material within the lumen of the blood vessel and fibrosis were noted. The interpretation was of medium vessel vasculitis, suggestive of PAN, with differential diagnosis including anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis and vasculitis caused by another rheumatic disease, less likely erythema induratum. The patient had been directed to come to the hospital for further evaluation.

The patient did not recall any preceding acute illnesses, vaccinations, animal or insect bites, travel or sick contacts. He denied any history of skin, joint, gastrointestinal, autoimmune or sexually transmitted diseases. He reported being predominantly indoors for work, though he occasionally did yard work at home. He had been taking NSAIDs, acetaminophen and tramadol for his symptoms with limited effect; he otherwise did not regularly take medications.

He denied any of the following symptoms: sore throat, cough, nasal congestion, hearing loss, chest pain, shortness of breath, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, numbness, tingling, muscle pain or weakness, genital discharge, dysuria and hematuria. The patient reported living with his wife and newborn baby. He denied any use of illicit drugs. He also denied any family history of psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, thyroid disease, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune disease.

The patient’s physical exam was notable for normal cardiac, pulmonary, abdominal and neurological exams; an erythematous, tender, nodular rash overlying both lower extremities, the mons pubis and lower abdomen (see Figure 1); tenderness without overt synovitis in both elbows; and a warm effusion of his left knee.

Extensive diagnostic testing was performed. Notable findings included normal renal function; elevated alkaline phosphatase at 125 U/L (reference range [RR]: 9–122 U/L) with normal bilirubin, AST and ALT; leukocytosis with 17.9×103 cells/μL white blood cells (WBC; RR: 4.0–11.0×103 cells/μL); and neutrophilia with absolute neutrophil count of 13.24×103 cells/μL (RR: 2.00–7.60×103 cells/μL); mild anemia with hemoglobin of 12.4 g/dL (RR: 13.2–17.1 g/dL); thrombocytosis with platelet count of 498×103 cells/μL (RR: 150–420×103 cells/μL); and elevated, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein of 234.5 mg/L; normal procalcitonin and elevated antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer of 959 IU/mL (RR: ≤200 IU/mL).

Tests were negative for COVID-19, group A Streptococcus, urine chlamydia and gonorrhea, syphilis, QuantiFERON, Lyme antibody, Rickettsia IgG and IgM, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B total core antibody, hepatitis C antibody and human immunodeficiency virus. Parvovirus DNA was not detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Blood cultures failed to identify a pathogen.

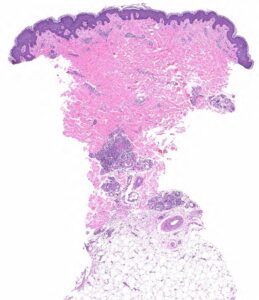

FIGURE 2A: Punch biopsy demonstrates an uninvolved epidermis with focal mid to deep dermal vasculocentric inflammation (H&E stain, 2x). (Click to enlarge.)

Rheumatoid factor was mildly positive at 17 IU/mL (RR: <14 IU/mL); antinuclear antibody (ANA) was 1:80, dense and fine speckled (RR: <1:80); angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) was normal. ANCA, myeloperoxidase antibodies (MPO), proteinase 3 (PR3) and cryoglobulin tests were negative. C3 and C4 were normal. Urinalysis returned 1+ protein and 1+ ketones; urine protein/creatinine was 0.10 mg/1.0 mg (RR: <0.10 mg/1.0 mg). Serum protein electrophoresis was normal, and serum free

kappa/lambda was absent.

Chest X-ray and transthoracic echocardiogram were unrevealing.

Left knee joint aspiration yielded turbid, yellow synovial fluid, with 10,301 nucleated cells/μL (RR: ≥2,000 nucleated cells/μL is classified as inflammatory synovial fluid), less than 3,000 red blood cells and no crystals. Synovial fluid culture did not yield an organism.

The patient was evaluated by a dermatologist, who felt his cutaneous lesions were likely consistent with cutaneous PAN, which may be associated with group A Streptococcal infection. Differential diagnosis included panniculitis (including erythema nodosum, which may also be associated with group A Streptococcal infection, but would appear as septal panniculitis rather than medium vessel vasculitis; and erythema induratum, which may be associated with tuberculosis), ANCA-associated vasculitis, subcutaneous nodules of rheumatic fever and atypical infection. A repeat punch biopsy of the patient’s rash was performed.

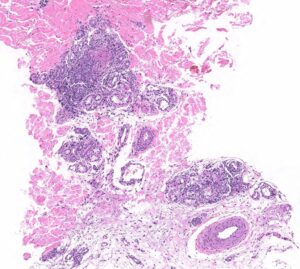

FIGURE 2B: Mid to deep dermal vasculocentric mixed inflammation with relatively unaffected deep dermal vessels (H&E stain, 10x). (Click to enlarge.)

The patient was started on treatment for rheumatic fever with 10 days of cephalexin because he met the 2015 American Heart Association revised Jones major criterion of subcutaneous nodules and minor criteria of polyarthralgia, fever of ≥38.5ºC and a CRP ≥3 mg/dL. He was also started on ibuprofen and colchicine for suspected cutaneous PAN. (Note: Penicillin was avoided due to the patient’s drug allergy.)

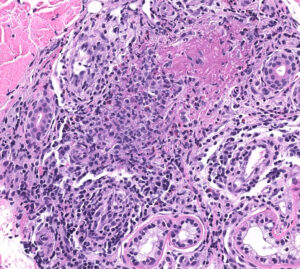

The skin biopsy performed during the patient’s hospitalization showed vasculo-centric inflammation of the medium-sized vessels and relative sparing of the small vessels in the mid and deep dermis, with an inflammatory infiltration composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils in the vessel walls and fibrin obscuration of vessel lumina (see Figures 2A–C). These results were consistent with medium vessel vasculitis, with ANCA-associated vasculitis in the differential diagnosis.

The skin tissue culture grew 1+ coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, which was thought to be a contaminant. Because the patient developed new skin lesions despite the aforementioned therapy, the dermatologist recommended adding prednisone at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg daily, with planned taper over 28 days. The patient was discharged following clinical improvement on steroids, with outpatient rheumatology and dermatology follow-up.

Discussion

FIGURE 2C: Vasculocentric inflammation consisting of lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils with obscuration of vessel walls and fibrin deposition (H&E stain, 20x).

PAN is a rare, necrotizing, predominantly medium-vessel vasculitis first described in 1852, with its cutaneous-limited form described in 1931. Characteristic histopathology of cutaneous PAN is leukocytoclastic vasculitis in small- to medium-sized arterioles of deep dermis or hypodermis, with or without fibrinoid necrosis. Most cases of cutaneous PAN are idiopathic, but up to 40% may be associated with infection (group A Streptococcus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, recurrent urinary tract infections, parvovirus B19 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis), as well as inflammatory bowel disease and long-term exposure to minocycline.5,6

Given the rarity of cutaneous PAN and its predominant distribution among individuals in their 40s or 50s, we considered a wide differential diagnosis for this patient when carrying out our evaluation, including infectious (e.g., disseminated gonococcal infection, syphilis, parvovirus B19 infection, Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, infective endocarditis, septic arthritis, tuberculosis), post-infectious (e.g., reactive arthritis, acute rheumatic fever) and rheumatological (e.g., ANCA-associated vasculitis, cryoglobulinemia, polyarteritis nodosa, sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, crystalline arthritis) etiologies.5

He was ultimately diagnosed with cutaneous PAN via skin biopsy, with high-titer ASO suggestive of antecedent group A Streptococcal infection and possible subsequent rheumatic fever, and his treatment was tailored to this diagnosis. He had no apparent deep organ involvement to suggest a systemic vasculitis. Continued monitoring and heightened awareness are important moving forward, given the often chronic and relapsing course of cutaneous PAN and possible progression to systemic PAN.

Dr. Vania Lin

Vania Lin, MD, MPH, is a rheumatology fellow at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.

Dr. Rebecca Johnson

Rebecca Johnson, MD, recently completed the Dermatopathology Fellowship Program at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.

Dr. Suter

Lisa Suter, MD, is a professor of medicine in the Section of Rheumatology at the Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.; she is also director of quality measurement programs at the Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation (CORE).

Disclosures

Outside the submitted work, Dr. Suter receives support for directing a federal contract, the Measure & Instrument Development Support (MIDS) contract; Development, Reevaluation and Implementation of Outcome/Efficiency Measures for Hospital and Eligible Clinicians, funded by the CMS; and during the conduct of the study, grants from Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH). Dr. Suter received $5,000 or less per year in consulting fees to Dr. Losina, PI, on an NIH grant through BWH to study knee osteoarthritis.

References

- Haugeberg G, Bie R, Bendvold A, et al. Primary vasculitis in a Norwegian community hospital: A retrospective study. Clin Rheumatol. 1998;17(5):364–368.

- Reinhold-Keller E, Zeidler A, Gutfleisch J, et al. Giant cell arteritis is more prevalent in urban than in rural populations: Results of an epidemiological study of primary systemic vasculitides in Germany. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000 Dec;39(12):1396–1402.

- Mahr A, Guillevin L, Poissonnet M, Aymé S. Prevalences of polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and Churg-Strauss syndromein a French urban multiethnic population in 2000: A capture-recapture estimate. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Feb 15;51(1):92–99.

- Pagnoux C, Seror R, Henegar C, et al. Clinical features and outcomes in 348 patients with polyarteritis nodosa: A systematic retrospective study of patients diagnosed between 1963 and 2005 and entered into the French Vasculitis Study Group Database. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Feb;62(2):616–626.

- Daoud MS, Hutton KP, Gibson LE. Cutaneous periarteritis nodosa: A clinicopathological study of 79 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1997 May;136(5):706–713.

- Criado PR, Marques GF, Morita TCAB, de Carvalho JF. Epidemiological, clinical and laboratory profiles of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa patients: Report of 22 cases and literature review. Autoimmun Rev. 2016 Jun;15(6):558–563.