Clinical Photography, Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, UK/Science Source / shutterstock.com

CHICAGO—Physicians from the University of Chicago presented an intriguing case of Sweet’s syndrome for the Clinical Pathological Conference during the 2018 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting.

Pankti Reid, MD, MPH, a rheumatology fellow at the University of Chicago, introduced the case of a white man who, in 2017, came under the care of the University of Chicago. She explained that in 2015, the then 56-year-old man presented at a different institution, where he was diagnosed with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. The diagnosis was based on a presentation of uveitis, fever, cough, weight loss, cytopenia, a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate and high C-reactive protein. That institution prescribed rituximab and prednisone.

In 2017, when the patient arrived at the University of Chicago, his symptoms included fever, night sweats, weight loss and fatigue. “Overall, he was just an ill-looking gentleman,” said Dr. Reid. Even though he was receiving rituximab, he was unable to reduce prednisone to below 20 mg daily without recurrence of arthralgias and fatigue. He had been suffering from fever for approximately three weeks and had a nonproductive cough. His oxygen level was 95% on room air, and he was diaphoretic. Laboratory tests revealed 90% neutrophilia and low hemoglobin at 6.7 g/dL. A thorough infectious agent workup was conducted, with unremarkable results.

He was admitted to the hospital where he experienced recurring fevers, despite 72 hours of treatment with antibiotics. While hospitalized, he also had signs of volume overload and was treated with aggressive diuresis.

Pulmonary Imaging

Jonathan H. Chung, MD, section chief of thoracic radiology and associate professor of radiology at the University of Chicago, continued the presentation with a discussion of the patient’s pulmonary imaging. “A lot of time, as a radiologist, I can’t give you a specific diagnosis,” said Dr. Chung, who explained that when he sees something on an image, it could be water, blood, pus, cells or inflammation. In this case, the computed tomography (CT) scan could have meant the patient had pulmonary hemorrhage, pneumonia or aspiration leading to pneumonia.

Dr. Chung described in detail the visible abnormality in the patient’s lung, which looked like a tree-in-bud nodularity and was consistent with aspiration pneumonia. Although typically such an image is diagnostic of aspiration pneumonia, he reminded the audience the image was showing something in the bronchioles, and he noted vasculitis can also manifest as a tree-in-bud nodularity. In the case of this patient, 27 days after admission, the tree-in-bud nodularity had worsened, suggesting more fluid in the lungs.

To be diagnosed with Sweet’s syndrome, patients must present with dermatosis, expressed by the abrupt onset of painful plaques/nodules, & a pathology showing dense neutrophilic infiltrate & no leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Histological Results

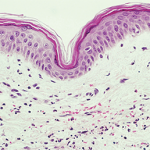

Aliya Husain, MD, professor of pathology at the University of Chicago, took the stage to describe the patient’s histological results. The University of Chicago team performed a skin biopsy in 2017 that revealed superficial and deep dermal infiltration of neutrophils with perivascular localization but without vasculitis. The patient also had dermal edema. Taken together, the results were consistent with neutrophilic dermatitis.

In addition, the 2017 transbronchial biopsy showed interstitial inflammatory infiltrate composed predominantly of neutrophils. Because the infiltrate also included macrophages, it was properly termed a mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Dr. Husain then revisited the 2015 histology from a transbronchial biopsy. The 2015 lung biopsy also revealed neutrophilic infiltrate that, given the clinical context, was consistent with Sweet’s syndrome.

Diagnosis

Anisha Dua, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, finished the session by examining the diagnosis of Sweet’s syndrome with pulmonary involvement in this patient. The syndrome was first identified in 1964 by Dr. Robert Sweet, who proposed it be called acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Despite his suggestion, it was eventually named Sweet’s syndrome. Sweet’s syndrome can be classified as classical/idiopathic, malignancy associated or drug induced. The most common drug-induced cause of Sweet’s syndrome is granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, although anti-neoplastics have also been associated with the syndrome.

To be diagnosed with Sweet’s syndrome, patients must present with dermatosis, expressed by the abrupt onset of painful plaques/nodules, and a pathology showing dense neutrophilic infiltrate and no leukocytoclastic vasculitis, Dr. Dua said. In addition, the vast majority (80–90%) of patients have a fever. Extracutaneous manifestations of Sweet’s syndrome can include ocular involvement (17–72% of patients), and Dr. Dua reminded the audience this patient had experienced uveitis in 2015. Sweet’s syndrome can also include pulmonary involvement, which presents most commonly as progressive dyspnea and dry cough.

Treatment

Once the doctors at the University of Chicago made the diagnosis, they turned to the medical literature to determine how best to manage the patient. They found a review of 44 cases of adult Sweet’s syndrome with pulmonary involvement. All of the patients in the case series received steroids, and although most improved, 14 either did not improve or improved and then got worse again. The 14 patients who progressed despite steroids had an underlying malignancy or an autoimmune disease, and Dr. Dua noted more than half—55%—of the pulmonary Sweet’s syndrome cases had an underlying malignancy.

The physicians at the University of Chicago treated their patient with pulse steroid therapy followed by a dose of 1 mg/kg daily. The patient ultimately transitioned to oral cyclophosphamide, which resulted in significant benefits.

Dr. Dua concluded the session with two points: Pulmonary manifestations of Sweet’s syndrome can present prior to skin manifestations, and it is important to evaluate patients with pulmonary Sweet’s syndrome for an underlying malignancy.

Lara C. Pullen, PhD, is a medical writer based in the Chicago area.