BALTIMORE—The eye may be the window to the soul, but in medicine it can also serve as a harbinger of systemic disease. At the 18th Annual Advances in the Diagnosis and Treatment of the Rheumatic Diseases, held May 13–14 at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Meghan Berkenstock, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, gave a presentation on the connection between rheumatology and ophthalmology.

BALTIMORE—The eye may be the window to the soul, but in medicine it can also serve as a harbinger of systemic disease. At the 18th Annual Advances in the Diagnosis and Treatment of the Rheumatic Diseases, held May 13–14 at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Meghan Berkenstock, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, gave a presentation on the connection between rheumatology and ophthalmology.

Dr. Berkenstock discussed three main topics: 1) the association of uveitis with systemic disease, 2) medications and vaccinations that can be associated with the development of uveitis, and 3) when it’s appropriate to refer patients to an ophthalmologist.

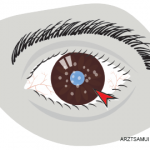

Uveitis is an umbrella term for intraocular inflammation that can apply to more than 30 different syndromes, Dr. Berkenstock explained. The etiologies of uveitis can be autoimmune, infectious, neoplastic or idiopathic, and one or more chambers of the eye can be affected. Inflammation of the eye is a rare phenomenon because the eye is generally an immune-privileged site.

Rheumatic Disease

In rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and secondary Sjögren’s syndrome associated with keratoconjunctivitis sicca, patients may experience eye dryness, foreign-body sensation, photophobia and red eyes. An increased risk for external infections exists secondary to decreased tear turnover and breakdown of surface epithelium, which can lead to painful and recurrent filamentary keratitis.

Treatments for dry eye associated with Sjögren’s syndrome include artificial tears, punctal plugs, topical cyclosporine or tacrolimus, lifitegrast, oral pilocarpine, scleral lenses and autologous serum tears. One of the newest treatments approved by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration for the management of dry eyes is varenicline nasal spray, which may be helpful for select patients.

Patients with RA can also develop scleritis or episcleritis, Dr. Berkenstock explained. If a patient develops scleritis associated with peripheral corneal melting (i.e., peripheral ulcerative keratitis), it’s particularly important to evaluate for the possibility of underlying RA. For episcleritis in RA, this condition is typically self-limited but can recur, and treatment may involve topical glucocorticoids and topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

In patients with scleritis, it’s important to evaluate for conditions beyond RA, such as HLA-B27-associated spondyloarthritis, Lyme disease, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis and sarcoidosis. The treatment of scleritis typically begins with oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and can escalate to systemic glucocorticoids—up to the equivalent of 1 mg/kg of prednisone daily. If inflammation recurs before tapering to 7.5 mg or less of prednisone daily, then methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) inhibitors, should be considered.