As the coronavirus pandemic unfolds, hospitals and clinics across the world are facing ever-evolving changes to practices and workflows. Our rheumatology clinics have had to develop novel ways to communicate ever-evolving information to staff, administrators and physicians.

As the coronavirus pandemic unfolds, hospitals and clinics across the world are facing ever-evolving changes to practices and workflows. Our rheumatology clinics have had to develop novel ways to communicate ever-evolving information to staff, administrators and physicians.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classified COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11. As the clinic director of CarePoint East Rheumatology and Nephrology Clinics, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center (OSUWMC), Columbus, I began receiving a plethora of questions, the answers to which seemed to change almost by the minute. I was fielding numerous clinical and clinic operational questions, and it seemed emails I sent one day became outdated the next.

At the onset of the pandemic, our division was relying primarily on group emails to disseminate daily information. In addition, we instituted numerous meetings at all levels, including university-, department-, division- and clinic-wide, but information from these meetings still needed to be relayed to those not present. Email became the de facto means for distributing these updates.

However, in this rapidly changing environment, email proved problematic. Rather than keeping everyone on the same page, email seemed to breed more divisiveness. Although a group email may be sent to everyone at the same time, a single message spawned a wide web of individual emails, texts, phone calls and curbsides. While some in the group would reply to all, many would choose to send individual messages or contact me by other means.

Rather than keeping everyone on the same page, email seemed to breed more divisiveness.

Email also failed to serve as a stand-alone resource. The first group email I sent out, on the day the WHO announced the pandemic, had the subject line Coronavirus Resources. It contained updates regarding hospital screening policies, links to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) website and a rheumatology-centered patient handout related to COVID-19. Rather naively, I hoped our staff and physicians could reference this single email in the early days of the pandemic. However, soon after that email was sent, newer information was available, which required follow-up emails.

These follow-up emails were buried in in-boxes that were already filled to capacity. With multiple coronavirus emails coming daily from numerous senders, crucial information regarding divisional operating procedures or COVID-19 was too easy to miss.

With this high volume of messages, it became an exercise in hunting, trying to track down the answer to a specific question somewhere in one of the many recent emails. Searching for a specific email was challenging when they all had similar subject headings related to COVID-19. Over time, these many emails also led to coronavirus email fatigue. Given the sheer volume of messages coming in, not all of the information seemed to be fully processed by recipients.

It was clear within the first few days of the pandemic that email could not serve effectively as a stand-alone resource.

Emails also led to confusion regarding which decisions were paramount. Multiple meetings occurred daily as the pandemic unfolded. Decisions regarding operating procedures made one day were changed the next. Unfortunately, some of our lead staff did not always know which process to follow: Should they follow the process discussed in person with the clinic director or the one described in an email that came from the university later that day? Without establishing a primary mode of communication, confusion reigned over which practice model was current.

Practice Shift

The challenges of emails during this crisis demanded a change in how we, as a division and as a multidisciplinary practice with multiple clinic locations, communicate. We needed a single resource that providers, nursing staff and administrators could easily reference at any time and that could be updated without necessarily getting lost in side conversations or buried under emails. We also needed something collaborative, which would allow everyone to contribute their information readily, as they discovered it. Finally, while I had taken the lead in defining our division’s operating procedures during the pandemic, I was well aware that given the increasing prevalence of COVID-19, a real possibility existed that I might not be in a position to continue to lead if I became ill. I needed a communication platform that was easy enough for just about anyone to take over if I were unable to continue in my role.

The key to solving this problem was staring me in the face. The solution was on the university medical center’s home page, right after the email and help buttons: collaboration.

Clicking on the collaboration button opened OSWUMC’s information page regarding collaborative websites, specifically SharePoint. SharePoint is a Microsoft product built as a portal for Office documents that has been expanded to include information lists, a calendar, links, tasks, and other resources. This one site allows authorized users access to all information in one centralized location.

Collaboration-based websites allow multiple members the ability to edit the site. Rather than a regular website that only administrators can edit content, these sites allow any authorized member the ability to essentially run the basic functions of the site. Editing or creating content is relatively easy. Users need only a basic understanding of Microsoft Word. Word documents can be stored and checked into a virtual library for all users and members to reference. Any edits to the documents require them to be checked out first, then checked back in to be shared among users.

SharePoint is a secure tool approved for health systems, unlike other collaborative web-based platforms like Google Docs and Dropbox. OSUWMC’s Department of Information Technology (IT) security has found SharePoint acceptable to use for two levels of information.

The first level is non-protected health information (PHI), which is the level of our site. Our Rheumatology COVID-19 Updates site contains basic updates on coronavirus, new work processes specific to our clinic and schedules for clinic and hospital duties.

The second level is for information that contains PHI. These sites require more restrictions. A non-PHI site is allowed to self-govern who has access to the site, whereas, at OSUWMC, a secure site requires a security team to grant access.

Creating the site required a simple request to our IT department. In less than a day of requesting a Rheumatology COVID-19 Updates SharePoint site, approval was granted. I was soon able to assemble the scores of emails that had filled my in-box and numerous notes scribbled down from meetings into discrete documents that could be stored and shared on the site.

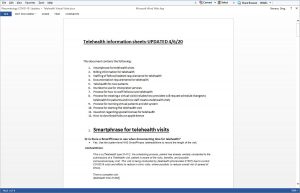

When we first launched the site, we included links to the OSUWMC COVID-19 page, which had the most updated information from the medical center regarding the pandemic. We started with six key documents: contingency plans for inpatient consults; clinical screening guidelines for suspected COVID-19 patients; a patient information handout; information on how to send out blast messages to patient panels over the patient portal; clinic-building entry policies for employees; and information on telehealth visits, including processes and billing information.

Each time a new document is added, it comes with metadata embedded. These include who created the document, when it was created, as well as who modified it last and when it was last modified. This is visible to the user when they look at the list of documents. Additional fields can be added if necessary. Document history can be turned on, making it possible to review a previous version of the document. This feature is deactivated by default because it can greatly increase the space taken up by a site.

SharePoint is secured as an invitation-only site. It has various levels of users, which include administrators, members and visitors. As the site creator, I was assigned the role of administrator. The IT department also granted our division administrator privileges. As administrators, we have the ability to control some of the site settings, including inviting members and visitors.

I invited rheumatology physicians, fellows, nurse practitioners and administrators to be members of this site. Members have the ability to edit existing documents or to create new ones.

I invited our clinical nephrology collaborators, nursing staff and office staff to be visitors to the site. Visitors have the ability to view all documents but are not able to edit them or create new documents. This was important because any changes to workflow processes would have to be approved by the physicians and administrators and could not be simply edited by a staff member without leadership approval.

In Practice

Our SharePoint has been in full operation for three weeks (as of April 7). Some of the original documents have been updated as processes have changed. Newer documents and links include the latest guidelines issued by the State of Ohio Board of Pharmacy for prescribing anti-malarial drugs and processes for inpatient electronic consultations (e-consults). At the time of writing, we have developed 23 documents for the site.

Rather than referring to old emails, staff, administrators and physicians now have a central, stand-alone resource. Once any division decision is made, the site is updated to serve as the most current repository of divisional processes and information.

It’s important to note that SharePoint does not fully replace email. We still use email to communicate some information that needs to be distributed as it unfolds, but in these communications, I note the SharePoint is also being updated to reflect this information.

Now, when I get questions from our division, I can direct people to a definitive resource. Having a centralized repository for constantly changing information has dramatically improved communications during the pandemic. Not only do we now have a stand-alone resource that can easily be updated by any member, it has dramatically cut down the number of emails we send and receive. From the first week of the pandemic (when we relied heavily on email) to the second week (when we switched to SharePoint), the volume of my work email related to coronavirus was cut in half, despite the rapidly changing rules for telehealth, remote working and the prescription of anti-malarials that came out in the second week.

SharePoint has dramatically improved my ability to lead and to communicate change during this coronavirus pandemic. The site is secure, and adoption is fast and relatively easy. Implementing a document-sharing, web-based platform, such as SharePoint, could improve communications for other clinics and medical divisions during the COVID-19 pandemic or in other situations in which information is rapidly evolving and affecting multiple people.

For more information on SharePoint or similar tools, contact your IT department or refer to Microsoft Office tools: https://products.office.com/en-us/sharepoint/collaboration.

Sheryl Mascarenhas, MD, is the clinic director of CarePoint East Rheumatology and Nephrology Clinics at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center and the associate program director for the rheumatology fellowship program. She is also the national vice president for Phi Rho Sigma Medical Society.

Greg Stevens is a systems analyst for the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. He received his Bachelor of Science in Systems Engineering from The Ohio State University.