Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most used drugs for acute and chronic pain. More than 30 billion doses of NSAIDs are consumed annually from more than 70 million prescriptions.1

Despite their common use, NSAIDs are not free of serious toxicities. In the pre-Vioxx (rofecoxib) era, gastrointestinal toxicity was the primary concern for many NSAIDs. In 1999, Wolfe et al. demonstrated the increasing rate of hospital admissions due to NSAID toxicity, thought mostly to be due to gastrointestinal (GI) side effects.2,3

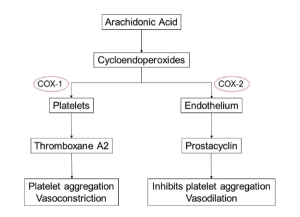

This led to the development and use of selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX‑2) inhibitors, the first of which was celecoxib, released in 1998, followed soon by rofecoxib in 1999 and several others.4,5 These agents had no effect on COX-1, an enzyme responsible for production of cytoprotective prostaglandin E2 and I2 in the stomach and, hence, had reduced risk of GI side effects.6

An exponential rise in the use of these drugs occurred.5 Simultaneously, strong evidence demonstrating that many of these agents confer a risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and other cardiovascular events developed.

The Mechanism of NSAID Cardiovascular Risk

The relation of MI risk and COX-2 inhibition is most noted in a study conducted by Garcia-Rodriguez et al.7 They noted a direct correlation between MI risk and the degree of COX-2 over COX-1 inhibition. The exact mechanism of COX-2 inhibition remains unknown, but the hypothesis of an imbalance between thromboxane

A2 (which promotes platelet aggregation and acts as a vasoconstrictor) and prostacyclin (an inhibitor of platelet aggregation and a vasodilator), produced by both platelets and endothelial cells, has gained the most prominence.8-10

Similarly, it has been postulated that reduced prostaglandin synthesis due to NSAID use augments the Th-1 mediated immune response, which leads to increased proatherogenic cytokines. This ultimately leads to detrimental plaque remodeling, rupture and embolization of plaque.11

Researchers think the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis increases peripheral vascular resistance and reduces renal perfusion, glomerular filtration and sodium excretion, which would ultimately lead to fluid retention and further contribute to the cardiovascular toxicity.11

More than 88,000 Americans suffered myocardial infarction due to rofecoxib, & more than 38,000 died.

Myocardial Infarction

The Downfall of COX-2 inhibitors Selective inhibitors of COX-2 came under closer scrutiny after two landmark trials, the Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcomes Research study and the Adenomatous Polyp Prevention on Vioxx (APPROVe) studies.12,13 Both trials demonstrated an increased risk of cardiovascular events, which led to the withdrawal of rofecoxib from the market in 2004. It was subsequently estimated that more than 88,000 Americans suffered myocardial infarction due to this drug, and more than 38,000 died.

This led to scrutiny of other COX-2 inhibitory agents. Several other first- and second-generation COX-2 inhibitors, such as etorocoxib, lumiracoxib, parecoxib and valdecoxib, were associated with a similar cardiovascular risk.14-16

These studies demonstrated the possible role of COX-2 inhibition as a mechanism for cardiovascular risk. Subsequently, nonselective inhibitors of COX were also shown to be associated with cardiovascular toxicity risk.

A position statement by American Heart Association summarized the risk of myocardial infarction associated with NSAIDs.17 The position statement highlighted the cardiovascular toxicity of COX-2 inhibitors; even among nonselective COX inhibitors, there was an increased risk of MI with drugs that preferentially inhibited COX-2, such as diclofenac, which features a 60% increased risk. Notably, naproxen was not associated with an increased risk of MI in clinical trials or observational studies.

This seminal manuscript had two direct impacts. First, it led to rapid decline in the use of diclofenac, in addition to COX-2 inhibitors. Second, several other studies started examining the risk of MI with other nonselective inhibitors.

Among the COX-2 inhibitors, celecoxib has not been associated with the risk of MI. In 2016, the PRECISION trial (a non-inferiority trial) assessed cardiovascular outcomes among naproxen, ibuprofen and celecoxib users, and it did not show an increased risk of MI in celecoxib compared to the other groups.18 It also showed reduced GI toxicity with celecoxib. However, the majority of the patients did not receive more than 200 mg/day of celecoxib.

Such results were also noted in the Standard Care versus Celecoxib Outcome Trial.19 Hence, at lower doses, celecoxib may be a safe anti-inflammatory drug.20

Nonselective Inhibitors & MI Risk Over the past decade, several investigators have evaluated the risk of MI with other nonselective agents. Such studies have been conducted using large population databases, including the UK-CPRD database, the UK-THIN database, the Finnish national database, the Dutch-PHARMO database and the Canadian, Danish and Taiwanese national databases.7,21-24 In a meta-analysis and systematic review of these studies in 2013, the NSAIDs etodolac, indomethacin and diclofenac were associated with a risk of MI. The study also demonstrated a dose response relationship for diclofenac and COX-2 inhibitors, but these drugs remained unsafe even at low doses. Naproxen was again noted to be safe both at low and high doses.25-27

The meta-analysis also assessed the risk associated with (then) less frequently used drugs, such as meloxicam, and noted increased risk. Meloxicam is an increasingly popular analgesic today, and to evaluate whether its use conferred an increased risk of MI, we conducted a study using the UK-THIN database. We demonstrated a significantly increased risk of MI associated with meloxicam use, similar to that of diclofenac.

Another agent increasingly used due to its proven GI safety is nabumetone. Aside from a single Finnish observational study that demonstrates its safety with the heart, no other studies assess its cardiovascular risk.22

Heart Failure

Several clinical trials and observational studies have noted an increased risk of hospitalization for heart failure due to any NSAID use. A meta-analysis of more than 600 clinical trials conducted by Coxib and the traditional NSAID Trialists (CNT) Collaboration showed more than twofold increased risk of hospitalization due to heart failure across all NSAIDs assessed.27 In 2016, Arfè et al. assessed the hospitalization risk due to heart failure associated with individual NSAIDs using five population-based healthcare databases. Notably, the risk estimates for heart failure followed the same trend as that of MI. Coxibs, such as rofecoxib and etoricoxib, diclofenac, indomethacin and piroxicam doubled this risk. Naproxen was associated with 16% increased risk of hospitalization due to heart failure, and celecoxib was not associated with this risk.28

NSAIDs may impair renal function in patients with decreased effective circulating volume by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis. This leads to reduced glomerular filtration and sodium and water retention, which ultimately leads to decompensated heart failure in these patients. Even the selective COX-2 inhibitors have similar effects on the renal function.29

Stroke

NSAIDs can be associated with risk of ischemic stroke, but this risk has been less well described than heart failure and myocardial infarction. Although the APPROVe trial had very few stroke events, it was posited the risk would be similar to that of myocardial infarction. In fact, a meta-analysis of randomized trials did not show any increased risk of stroke with NSAID use.27 However, several observational trials have consistently shown increased risk with highly selective COX-2 inhibitors (except celecoxib, for which there are very divergent results) ranging from 30% to more than twofold increased risk. Similarly, not enough data are available regarding stroke risk and other NSAIDs.30

Conventionally, NSAIDs have been thought to be associated with hemorrhagic stroke due to inhibitory effect on the platelets, similar to the GI bleeding risk associated with NSAIDs. However, some studies suggest no association between NSAID use and hemorrhagic stroke.

Venous Thromboembolism

Although data for the association between NSAID use and thromboembolism are not as robust, there is growing evidence to suggest NSAID use can be associated with the risk of deep vein thrombosis, as well as pulmonary embolism. In fact, in meta-analysis conducted by Ungprasert et al. in 2015, use of any NSAID was associated with 80% increased odds of venous thromboembolism.31 We assessed the risk of thromboembolism with individual NSAIDs in a population-based cohort of osteoarthritis patients (to minimize confounding by indication). The risk was most noted with use of COX-2 inhibitors (including celecoxib) and nonselective COX inhibitor preferentially inhibiting COX-2 (i.e., diclofenac, meloxicam). Naproxen did not increase the risk of thromboembolism.32

Common Study Pitfalls

Aside from the initial randomized clinical trials assessing COX-2 inhibitors, diclofenac, ibuprofen and naproxen, most of the evidence for other medications come from observational studies, many of which were conducted in large population databases or claims databases. These studies afford large sample sizes representative of general population, which allows evaluation of less frequently used NSAIDs, such as meloxicam, indomethacin, etolodolac, nabumetone, etc.

Unfortunately, confounding by indication is a common problem across these studies. Investigators have attempted to mitigate this effect by using a cohort of osteoarthritis or other inflammatory arthritis patients. Similarly, some studies have compared cardiovascular risk of NSAIDs with non-users of NSAIDs, which can also bias the results.

Use of remote, recent and current users of NSAIDs instead of non-users could potentially reduce confounding. Finally, physician preferences of a particular NSAID, over-the-counter drug use and the effect of baby aspirin cannot be sufficiently accounted for in these studies.

Conclusions

NSAIDs are commonly used in routine clinical practice and, particularly, rheumatology practice. And perhaps for osteoarthritis, which is the most common form of arthritis, there are not many choices—clinicians are often forced to choose between NSAIDs and prescription opiates, both with their associated side effects. Also, clinicians must weigh other side effects such as GI toxicity (often much less with COX-2 inhibitors) and drug efficacy (recent meta-analysis suggests that diclofenac may be more effective) with cardiovascular toxicity.

Although the U.S. Food and Drug Administration warns for cardiovascular toxicity against all NSAIDs, naproxen’s cardiovascular safety has been demonstrated across clinical trials and observational trials. Celecoxib at lower doses has been shown to be safe from a cardiovascular standpoint, and it has a favorable GI safety prolife. Various observational studies have shown drugs that preferentially inhibit COX-2 over COX-1 (e.g., diclofenac, etodolac, meloxicam, etc.) have increased cardiovascular toxicity and should be avoided if possible. Finally, nabumetone seems to have remarkable GI safety, and initial observational studies have shown its cardiovascular safety.

In summary, current data suggest this reasonable pain treatment strategy:

- Start with nonsystemic NSAID analgesics, topical diclofenac or acetaminophen;

- Try naproxen next;

- Try celecoxib next, at a low (200 mg/day) dose; and finally

- Try other nonselective NSAIDs next, such as ibuprofen.

Deepan S. Dalal, MD, MPH, works in the Department of Medicine at Brown University Warren Alpert School of Medicine in Providence, R.I.

Maureen Dubreuil, MD, MS, works in the Department of Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine and the Division of Rheumatology in the Boston VA Healthcare system.

David T. Felson, MD, MPH, works in the Department of Medicine at Boston University School of Medicine and in the Arthritis Research UK Epidemiology Unit at the University of Manchester in Manchester, England.

References

- Wiegand T, Vernetti C. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) toxicity. Medscape. 2017 Dec 20.

- Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1999 Aug 12;341(7):1888–1899.

- Singh G. Recent considerations in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathy. Am J Med. 1998 Jul 27;105(1B):31S–8S.

- Hawkey CJ. COX-2 chronology. Gut. 2005 Nov;54(11):1509–1514.

- Halpern GM. COX-2 inhibitors: A story of greed, deception and death. Inflammopharmacology. 2005;13(4):419–425.

- Meyer-Kirchrath J, Schror K. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition and side-effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Med Chem. 2000 Nov;7(11):1121–1129.

- Garcia Rodriguez LA, Tacconelli S, Patrignani P. Role of dose potency in the prediction of risk of myocardial infarction associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Nov 11;52(20):1628–1636.

- Fitzgerald GA. Coxibs and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2004 Oct 21;351(17):1709–1711.

- Cryer B, Feldman M. Cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 selectivity of widely used nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 1998 May;104(5):413–421.

- Olsen AM, Fosbol EL, Lindhardsen J, et al. Long-term cardiovascular risk of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use according to time passed after first-time myocardial infarction: A nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2012 Oct 16;126(16):1955–1963.

- Padol IT, Hunt RH. Association of myocardial infarctions with COX-2 inhibition may be related to immunomodulation towards a Th1 response resulting in atheromatous plaque instability: An evidence-based interpretation. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010 May;49(5):837–843.

- Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000 Nov 23;343(21):1520–1528.

- Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 17;352(11):1092–1102.

- Cannon CP, Curtis SP, FitzGerald GA, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with etoricoxib and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in the Multinational Etoricoxib and Diclofenac Arthritis Long-term (MEDAL) programme: A randomised comparison. Lancet. 2006 Nov 18;368(9549):1771–1781.

- Farkouh ME, Greenberg JD, Jeger RV, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes in high risk patients with osteoarthritis treated with ibuprofen, naproxen or lumiracoxib. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Jun;66(6):764–770.

- Andersohn F, Suissa S, Garbe E. Use of first- and second-generation cyclooxygenase-2-selective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2006 Apr 25;113(16):1950–1957.

- Antman EM, Bennett JS, Daugherty A, et al. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: An update for clinicians: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007 Mar 27;115(12):1634–1642.

- Nissen SE, Yeomans ND, Solomon DH, et al. Cardiovascular safety of celecoxib, naproxen or ibuprofen for arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 29;375(26):2519–2529.

- MacDonald TM, Hawkey CJ, Ford I, et al. Randomized trial of switching from prescribed non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to prescribed celecoxib: The Standard care vs. Celecoxib Outcome Trial (SCOT). Eur Heart J. 2017 Jun 14;38(23):1843–1850.

- Felson DT. Safety of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 29;375(26):2595–2596.

- Garcia Rodriguez LA, Varas-Lorenzo C, Maguire A, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction in the general population. Circulation. 2004 Jun 22;109(24):3000–3006.

- Helin-Salmivaara A, Virtanen A, Vesalainen R, et al. NSAID use and the risk of hospitalization for first myocardial infarction in the general population: A nationwide case-control study from Finland. Eur Heart J. 2006 Jul;27(14):1657–1663.

- van Staa TP, Rietbrock S, Setakis E, et al. Does the varied use of NSAIDs explain the differences in the risk of myocardial infarction? J Intern Med. 2008 Nov;264(5):481–492.

- Shau WY, Chen HC, Chen ST, et al. Risk of new acute myocardial infarction hospitalization associated with use of oral and parenteral non-steroidal anti-inflammation drugs (NSAIDs): A case-crossover study of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance claims database and review of current evidence. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2012 Feb 2;12:4.

- Salvo F, Antoniazzi S, Duong M, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with the long-term use of NSAIDs: A review of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014 May;13(5):573–585.

- Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011 Jan 11;342:c7086.

- Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A, et al. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2013 Aug 31;382(9894):769–779.

- Arfè A, Scotti L, Varas-Lorenzo C, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of heart failure in four European countries: Nested case-control study. BMJ. 2016 Sep 28;354:i4857.

- Bleumink GS, Feenstra J, Sturkenboom MC, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and heart failure. Drugs. 2003;63(6):525–534.

- Varas-Lorenzo C, Riera-Guardia N, Calingaert B, et al. Stroke risk and NSAIDs: A systematic review of observational studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011 Dec;20(12):1225–1236.

- Ungprasert P, Srivali N, Wijarnpreecha K, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of venous thromboembolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015 Apr;54(4):736–742.

- Lee T, Lu N, Felson DT, et al. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs correlates with the risk of venous thromboembolism in knee osteoarthritis patients: A UK population-based case-control study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016 Jun;55(6):1099–1105.