‘What first got me interested in serum sickness was the fact that lupus patients had similar manifestations,’ explains Dr. Atkinson. … ‘In the sickest lupus group, C3 & C4 are still used in almost every categorization I know of … .’

Theory of Serum Sickness

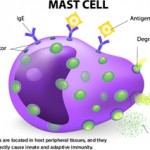

In the final section, Pirquet and Schick pulled together research from the existing human and animal literature and speculated about disease pathophysiology. Confusing the issue, the clinical manifestations did not completely coincide with the presence of precipitins found in the serum, which made the role of antibodies unclear.7 However, they posited that the symptoms of serum sickness were created by a chemical reaction between the horse serum and the patient’s antibodies.

They proposed:

We state the theory that there exists a causal connection between the formation of antibodies and [serum sickness].

As if to anticipate the resistance they were likely to receive, the two wrote:

The conception that the antibodies, which should protect against disease, are also responsible for the disease, sounds at first absurd. This has as its basis the fact that we are accustomed to see in disease only the harm done to the organisms and to see in the antibodies solely antitoxic substances.

They closed the monograph with a testament to their belief in the study’s worth and potential impact:

We believe to have shown that [serum sickness] has great importance, not only from a clinical viewpoint but also from the standpoint of general pathology: serum sickness is the best paradigma [sic] for a disease due to an organic cause which is unable to multiply, and is an exquisite object for the study of the changes going on in the system.

Follow-up & Response

Dr. Pirquet expanded on many of the ideas present in Die Serumkrankheit in his 1910 book, Allergy, written when he was a professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins. Here, Dr. Pirquet coined the term allergy (from the Greek roots “strange activity”).5 Since then, the term has taken on a more specific meaning, but then the distinction between allergy and immunity was not as clear.7

Dr. Silverstein explains, “In Allergy he tried to put together the observations that were known at the time, like skin reactions, the tuberculin reaction, serum sickness and anaphylaxis.” However, Dr. Silverstein notes that Dr. Pirquet did not think of himself as what we would call an allergist. He says, “There were no allergists at the time. People didn’t yet understand allergy and its basis.”

In Allergy, Dr. Pirquet made further observations, analyses and speculations about the pathogenesis of serum sickness. Here, he correctly identified immune complexes consisting of antigen and antibodies (“toxic bodies”) as the precipitating factor of the syndrome.5

Dr. Silverstein relates that for the most part, the importance of Die Serumkrankheit was not largely appreciated in the medical community. “It just wasn’t understood at the time, or it wasn’t paid attention to, because people were thinking of other things. So it didn’t really stimulate as one might have expected.”

Still, anti-sera treatments continued to be widely used over the next few decades. Although the pathophysiology of serum sickness was not yet proven, investigators during this time confirmed the clinical findings of Pirquet and Schick in several large retrospective studies of patients given such treatments.8,9 With the advent of antibiotics, far fewer people were given heterologous anti-sera. However, anti-sera treatments continued to be used in some applications, such as for the treatment of tetanus, rabies and botulism, and for snake and spider bites.10