And in 1952, a new, more rapid technique for producing cortisone made the drug much more widely available.3

However, the initial enthusiasm of both the medical community and the broader public became muted and even antagonistic in the early 1950s, as the long-term side effects of cortisone treatment became more known. It did not help that some early studies seeking to replicate Hench’s work, perhaps poorly designed or with compounds of questionable purity, came back equivocal as to cortisone’s efficacy. It was not until 1959 and later that the drug’s true efficacy became undeniably clear.3

Corticosteroids Today

Dr. Bucala points out that Dr. Hench’s work catalyzed thinking about a class of therapeutics that remain critically important to this day. He explains, “It’s not an overstatement to say that to shut down deleterious inflammation as quickly and as strongly as possible, particularly for life-threatening situations, nothing works faster or better than steroids, whether it’s lupus, vasculitis, spinal cord compression, or acute lung inflammation.”

Biologic therapies, although very effective for many inflammatory diseases, simply cannot work as quickly to shut down this response. “It’s hard to imagine practicing medicine today without having steroids available, not just for rheumatology, but for any inflammatory disease,” says Dr. Bucala.

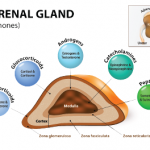

But rheumatologists and their patients must still grapple with the side effects first described by Drs. Hench and Kendall, as well as with others, such as immunosuppression, osteoporosis and cardiovascular effects. Prednisone and prednisolone, now used more commonly than cortisone, were developed in the 1950s; these had greater efficacy and less effect on undesirable mineralocorticoid receptors compared to cortisone. Yet intense efforts over many years to chemically modify corticosteroids to decrease their side effect profile have largely failed to date. Non-systemic methods of administration (e.g., nasal, topical or intra-articular) can work in some medical applications with reduced side effects, but their use is limited in rheumatologic diseases.3

In recent years, the trend in rheumatology has been to decrease doses of steroids, when possible, as seen in several ACR guidelines. Dr. Burns points out, “One of the holy grails of rheumatology is to get rid of the need for prednisone, especially at high doses. We’ve made some progress on that, but not a lot.”

Dr. Bucala also points out that because steroids are so effective, it’s sometimes hard to completely replace them in longterm treatment, such as for patients with systemic lupus or temporal arteritis.