In 1949, the first description of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) given cortisone sent shockwaves through the medical community, quickly capturing the public imagination as well. The paradigm-shifting report paved the way for the use of cortisone and related drugs in RA and many other medical conditions.1 The following is a discussion of some of the context of that pivotal study and some continued questions that remain—more than 70 years later—about the optimal use of these critical agents.

In 1949, the first description of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) given cortisone sent shockwaves through the medical community, quickly capturing the public imagination as well. The paradigm-shifting report paved the way for the use of cortisone and related drugs in RA and many other medical conditions.1 The following is a discussion of some of the context of that pivotal study and some continued questions that remain—more than 70 years later—about the optimal use of these critical agents.

RA in the Pre-Steroid Era

Treatment for RA in the 1940s was extremely limited, and many patients experienced long-term deformity and severe disability from their disease. Treatment consisted largely of bed rest, sometimes encouraged via hospitalization; physical therapy (e.g., exercises, massage, joint bracing); vitamins; aspirin; gold salt injection therapy; and, sometimes, experimental therapies.2

Other treatments included fever therapy, removal of presumed infectious foci (e.g., tonsillectomy) and vaccine therapy (from various bacterial strains), although these were falling out of fashion by the 1940s. These therapies were based on the infectious theory of RA, which posited the disease was caused by some sort of infection, either as a direct response to infection, from exposure to an infection-related toxin or to an infection-related allergic response. At the time, RA was even referred to as “chronic infectious arthritis” at times, although that theory had begun to wane by the 1930s.2

Dr. Bucala

Richard Bucala, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Rheumatology, Allergy and Immunology at Yale, New Haven, Conn., points out that at the time, it was known that joint inflammation occurred after streptococcal throat infection in the condition rheumatic fever. “So the fact that a pathogen or infection might be the cause of rheumatoid arthritis was obviously an open idea.”

Anti-Rheumatic Substance X

In 1926, Philip S. Hench, MD, the first author of the later paper on cortisone in RA, became the first head of the Mayo Clinic’s first rheumatology service in Rochester, Minn.2 Beginning in 1929, Dr. Hench made a series of observations that helped lead to his insight to try cortisone in patients with RA.3

Through multiple papers, Dr. Hench described how jaundiced patients sometimes experienced a remission in their RA symptoms, as did pregnant women. He even went as far as using toxins to induce jaundice in patients, which did temporarily improve arthritis symptoms in some patients. Dr. Hench began to speculate that some sort of naturally occurring substance produced in the body, which he termed “substance X,” accounted for improvement in these disparate situations.3

Dr. Hench described antecedent work for the groundbreaking 1949 paper:1

Even though the pathologic anatomy of rheumatoid arthritis is more or less irreversible, the pathologic physiology of the disease is potentially reversible, sometimes dramatically so. Within every rheumatoid patient corrective forces lie dormant, awaiting proper stimulation. Therefore, the disease is not necessarily a relentless condition for which no satisfactory method of control should be expected. The inherent reversibility of rheumatoid arthritis is activated more effectively by the intercurrence of jaundice or pregnancy than by any other condition or agent thus far known. Regardless of the supposed validity of the microbic theory, rheumatoid arthritis can be profoundly influenced by phenomena which are primarily biochemical.

Dr. Hench

In terms of underlying physiology, Dr. Bucala points out that pregnancy is, in fact, a high-steroid state, and estrogens themselves have some anti-inflammatory effects. Liver disease may also temporarily increase steroid levels through impaired metabolism of endogenous steroids and/or their increased production, as can happen in response to noxious stimuli.

Although the origins of his next insight aren’t completely clear, Dr. Hench began to suspect that substance X might be produced by the adrenal gland. Christopher M. Burns, MD, associate professor of medicine at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, N.H., points out that they knew at the time that adrenally deficient patients with Addison’s disease had profound fatigue, similar to RA patients, and it was also known that surgery induced some sort of protective adrenal response.

“That was kind of where they started to think that it was an adrenal hormone that made rheumatoid arthritis better in these circumstances,” says Dr. Burns.

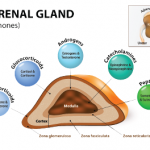

Zoning in on Compound E

In 1935, Dr. Hench began working with Edward C. Kendall, PhD, a professor of physiological chemistry at the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Kendall was already actively working to isolate physiologically active adrenal compounds. This was a laborious process that required thousands of pounds of animal adrenal glands to produce tiny quantities of product. Eventually, Drs. Hench and Kendall focused on the adrenal hormone termed “compound E” as potentially being the mysterious “substance X” that improved RA in multiple clinical situations.3

With the advent of World War II, the pharmaceutical industry became very interested in the production of an adrenal extract that might prove protective against stress. In fact, the U.S. government’s National Research Council made isolating such a compound their number one priority, due to its potential military implications.

Dr. Kendall

With input from Dr. Kendall, the pharmaceutical company Merck eventually developed a complicated 37-step synthesis process to synthesize compound E (i.e., 17-hydroxy-11-dehydrocorticosterone; cortisone) in 1948, at great expense. In September of that year, Drs. Hench and Kendall requested some compound E from Merck to be given to an initial patient with RA: Merck eventually sent 5 g.3

Dr. Hench and colleagues began administering the compound to Mrs. G, a 29-year-old patient with severe RA. She had come to Mayo to receive Hench’s jaundice-inducing treatment, but when this hadn’t worked, she refused to leave without further treatment; instead, her determination became a part of medical history.3

Compound E in 14 RA Patients

In their report published in 1949, Drs. Hench, Kendall and colleagues described Mrs. G’s transformative response to compound E, after being given 100 mg total daily via intragluteal injections:1

When she awoke [two days after her initial injection] she rolled over in bed with ease and noted much less muscular soreness. [The next day] painful morning stiffness was entirely gone. Scarcely able to walk three days previously, the patient now walked with only a slight limp… A week after the administration of compound E was begun, articular as well as muscular stiffness had almost completely disappeared, and tenderness and pain on movement, and even swellings, were markedly lessened.

Drs. Hench and Kendall also described in detail the response to compound E of 13 additional patients with moderately severe or severe polyarticular arthritis, who also experienced near miraculous transformations in response to the drug.

Study Methods

Drs. Hench and Kendall elaborated on their study methods, side effect profile, dose-effect response and laboratory effects, such as sedimentation rate. They also described the effect of pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone, which stimulates the production of multiple adrenal hormones, on two additional RA patients. This yielded similar therapeutic responses.1

“What really impressed me about the study was how carefully it was performed and reported, given our current perspectives,” notes Dr. Bucala. “Much less was then known about RA, but [Hench & Kendall] did some interesting things that are still more or less state-of-the-art in clinical investigation today.”

For example, Dr. Bucala highlights the use of the Westergren sedimentation rate as a marker of inflammation: The team saw that with the administration of compound E, the biomarker changed this blood test in predictable ways to indicate alleviation of the underlying disease. They also examined hemoglobin levels, a very sensitive marker of chronic inflammation, and showed decreased anemia of inflammation with treatment.

“And they also looked at things that have been highlighted by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration in the past few years, reporting on patient well-being. Patients’ appetites increased, and they had a sense of feeling well,” says Dr. Bucala. He notes that the researchers also performed a synovial biopsy after treatment, which showed reduced inflammation. “I think it speaks to their thoughtfulness and insight.”

Dr. Bucala also remarks on the use of longitudinal studies in some of the patients, in whom they first administered a control substance (cholesterol) followed by compound E, and in whom they tracked the sedimentation rate after decreasing the dose of compound E. “Basically, they used the patient as their own control, which is elegant to do today,” says Dr. Bucala. “It’s what we would now call a crossover study, where patients who first get the placebo then get the drug, and you see if there is a change.”

Dr. Burns

Dr. Burns agrees that although parts of the report are written more colloquially than would be done now, it does have some sophisticated aspects now considered essential for clinical trials.

“They did a washout period where [Dr. Hench] had patients stop their other medicines for a while before he gave them compound E,” says Dr. Burns. He also notes that the researchers used at least some blinding for the people administering compound E or the placebo injections, although this is not described in detail. “And they tried to take into account the placebo effect—also accounting for how rest and usual hospital care alone may improve the patient’s condition.”

Side Effects & Dose Response

Drs. Hench and Kendall also described some of the side effects seen in their patients: acne, mild hirsutism, facial rounding, fluid retention, weight gain, difficulty sleeping and euphoria. “They describe pretty accurately what everybody nowadays knows as the side effects of steroids,” notes Dr. Burns. “It’s interesting to think they are really the first people who saw them, and they are describing them so accurately. It’s pretty amazing how astute they were, even in a small number of patients.”

Partly to try to minimize such symptoms, Dr. Hench and colleagues experimented with lowering the dose of compound E. In the process, they describe a dose response. They tried decreasing the daily dose to 75 mg, 50 mg or even 25 mg, but patients flared, and their sedimentation rates rose in response. They wrote,

So far a minimal daily dose of 75 to 100 mg seems required, and sometimes such a dose does not entirely control symptoms and sedimentation rates. Perhaps small doses will be sufficient in cases in which the disease is mild.

Dr. Bucala notes that this therapeutic dose is roughly equivalent to a dose that might be used to manage an initial disease flare today (e.g., using the closely related synthetic glucocorticoid prednisone).

Theory & Speculation

The authors used their findings to speculate further on alternative theories to what they call the microbic theory, asking:

To what extent could rheumatoid arthritis be merely a syndrome produced by any factor which causes a deficiency of adrenal hormone?

“There are limits of that thinking that are obvious now today,” says Dr. Burns. “Immunology has advanced so much, and we know now that an infection can trigger long-term immune response, and you’d expect that to respond to steroids. But back then it was very novel thinking.”

Dr. Bucala also points out that although today we know that inflammatory diseases are not deficiencies of adrenal gland steroids per se, the pain and inflammation of these diseases does cause a stress response that results in relative adrenal deficiencies.

Drs. Hench and Kendall concluded by speculating that compound E might be helpful in other rheumatic and non-rheumatic medical conditions, particularly other conditions that Dr. Hench had previously described as sometimes going into remission during liver disease or pregnancy. They also reported that their preliminary results in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus were “encouraging.”1

Yet Drs. Hench and Kendall were careful to balance the optimism of the paper with caveats. They noted the practical challenges around compound E’s availability, which posed a significant barrier to ongoing investigation. They also remarked on the limited scope of this preliminary data, especially with respect to long-term use.

[This] make [s] inappropriate now the use of the term “treatment” except in an investigative sense. Much more experience is needed before we shall know how effective or safe the prolonged administration of compound E will be.

Public Response

In spite of this cautionary approach, compound E, soon renamed cortisone by Drs. Hench and Kendall, quickly captured the public’s attention.

In 1950, Dr. Hench, Dr. Kendall and Polish chemist Tadeus Reichstein, PhD (who had worked separately in Switzerland to isolate adrenal compounds), were awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine, just two years after Mrs. G received her first injection.3 In his acceptance speech, Dr. Hench reported that the compound decreased symptoms in most patients with RA, gout, lupus, psoriasis and ulcerative colitis.4

And in 1952, a new, more rapid technique for producing cortisone made the drug much more widely available.3

However, the initial enthusiasm of both the medical community and the broader public became muted and even antagonistic in the early 1950s, as the long-term side effects of cortisone treatment became more known. It did not help that some early studies seeking to replicate Hench’s work, perhaps poorly designed or with compounds of questionable purity, came back equivocal as to cortisone’s efficacy. It was not until 1959 and later that the drug’s true efficacy became undeniably clear.3

Corticosteroids Today

Dr. Bucala points out that Dr. Hench’s work catalyzed thinking about a class of therapeutics that remain critically important to this day. He explains, “It’s not an overstatement to say that to shut down deleterious inflammation as quickly and as strongly as possible, particularly for life-threatening situations, nothing works faster or better than steroids, whether it’s lupus, vasculitis, spinal cord compression, or acute lung inflammation.”

Biologic therapies, although very effective for many inflammatory diseases, simply cannot work as quickly to shut down this response. “It’s hard to imagine practicing medicine today without having steroids available, not just for rheumatology, but for any inflammatory disease,” says Dr. Bucala.

But rheumatologists and their patients must still grapple with the side effects first described by Drs. Hench and Kendall, as well as with others, such as immunosuppression, osteoporosis and cardiovascular effects. Prednisone and prednisolone, now used more commonly than cortisone, were developed in the 1950s; these had greater efficacy and less effect on undesirable mineralocorticoid receptors compared to cortisone. Yet intense efforts over many years to chemically modify corticosteroids to decrease their side effect profile have largely failed to date. Non-systemic methods of administration (e.g., nasal, topical or intra-articular) can work in some medical applications with reduced side effects, but their use is limited in rheumatologic diseases.3

In recent years, the trend in rheumatology has been to decrease doses of steroids, when possible, as seen in several ACR guidelines. Dr. Burns points out, “One of the holy grails of rheumatology is to get rid of the need for prednisone, especially at high doses. We’ve made some progress on that, but not a lot.”

Dr. Bucala also points out that because steroids are so effective, it’s sometimes hard to completely replace them in longterm treatment, such as for patients with systemic lupus or temporal arteritis.

Dr. Burns notes that we have made some progress, such as tocilizumab to treat giant cell arteritis: “That enables you to taper the prednisone more quickly or maybe get away with a minimal amount.” Another example is the recently approved complement inhibitor avacopan for granulomatosis with polyangiitis, which may offer practitioners a new means to reduce patients’ steroid use over the long term.

Dr. Bucala also points out that despite recent rheumatology trends, long-term, low-dose steroid therapy may still be helpful for some patients. For example, a recent study in The Lancet found that RA patients maintained on low-dose prednisone achieved better disease control than those who had been completely tapered off prednisone.5 “This notion of careful, judicious use of low-dose steroids is important and has value,” he adds. More than 70 years after Hench and Kendall’s report, rheumatologists are still debating the optimal use of this important class of compounds.

Readers seeking to learn more may want to read Dr. Burns’ article “The History of Cortisone Discovery and Development.”3 For a more comprehensive history on both the greater historical context and the personalities involved, see the comprehensive book, The Quest for Cortisone by Thom Rooke, MD.5

Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD, is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine. She is a freelance medical and science writer living in Bloomington, Ind.

Ruth Jessen Hickman, MD, is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Medicine. She is a freelance medical and science writer living in Bloomington, Ind.

References

- Hench PS, Kendall EC, Slocumb CH, et al. The effect of a hormone of the adrenal cortex (17-hydroxy-11-dehydrocorticosterone; compound E and of pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone on rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1949 Apr 13;24(8):181–197.

- Hunder GG, Matteson EL. Rheumatology practice at Mayo Clinic: The first 40 years—1920 to 1960. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010 Apr;85(4):e17e30.

- Burns CM. The history of cortisone discovery and development. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2016 Feb;42(1):1–vii.

- Hench PS. The reversibility of certain rheumatic and non-rheumatic conditions by the use of cortisone or of the pituitary adrenocorticotrophic hormone. Nobel Lecture. 1950 Dec 11. https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/henchlecture.pdf

- Burmester GR, Buttgereit F, Bernasconi C, et al. Continuing versus tapering glucocorticoids after achievement of low disease activity or remission in rheumatoid arthritis (SEMIRA): A double-blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020 Jul 25;396(10246):267–276.

- Rooke T. The Quest for Cortisone. East Lansing, Mich.: Michigan State University Press; 2012.