The uncommon presentation of granulomatous disease among CVID patients, as well as the consideration of alternative or overlapping infectious, autoimmune or malignant etiologies, poses a diagnostic & treatment challenge.

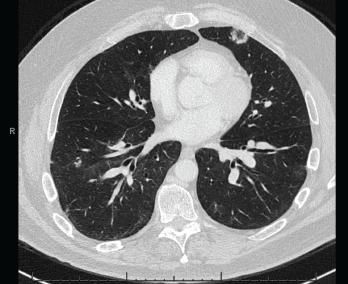

Figure 4. A CT scan of the chest without contrast showed multifocal, multilobar, subsegmental-sized opacities, which were nodules in some locations and more ill-defined lesions in others.

These findings were felt to be consistent with GLILD. IVIG was continued. Immunosuppression would be considered if the patient became symptomatic or if radiographic disease progressed.

Two years after the diagnosis of CVID, the patient remains clinically well and has not required immunosuppressive agents.

Discussion

Granulomatous disease is a rare manifestation of CVID. Necrotizing granulomatous inflammation is even less common.3–6 Further, clinical presentation with abdominal masses is highly unusual.7 The most commonly involved sites in CVID are the lungs, lymph nodes and spleen.2 The pathogenesis of CVID-associated granulomas remains unclear, although decreased switched memory B cells, increased CD8+ T cells and impaired CD4+ T cell response have been associated with granulomatous disease.2,8

Possible alternative or coexisting diagnoses, including infection, autoimmune disease and malignancy, complicate the diagnosis and treatment of CVID. The presence of concurrent pulmonary and abdominal granulomatous disease with necrotizing granulomas initially raised suspicion for mycobacterial infection, which classically presents with necrotizing granulomas.9

Other bacterial, fungal and viral etiologies, including Bartonella, Brucella, Nocardia, Tropheryma whipplei, Aspergillus, Coccidioides, Cryptococcus, Histoplasma and human immunodeficiency virus, were also considered.9,10 However, the lack of infectious symptoms and the extensive diagnostic evaluation did not support an infectious etiology in our patient.

Among autoimmune diseases, sarcoidosis, vasculitis and connective tissue disease were considered as potential diagnoses. Sarcoidosis affects the lungs and intrathoracic lymph nodes in over 90% of patients, though the disease may manifest in other organs as well. Sarcoidosis classically presents with noncaseating granulomas, along with mediastinal and hilar adenopathy, the latter of which was absent in our patient.11 Elevated angiotensin-converting enzyme level and hypergammaglobulinemia, which are reported with sarcoidosis, were absent as well.12

Table 1: Laboratory Tests

| Test | Result | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| Quantiferon-TB Gold | Negative | Negative |

| Coccidioides antibody, IgG by ELISA | 0.1 | ≤0.9 |

| Coccidioides antibody, IgM by ELISA | 0 | ≤0.9 |

| Coccidioides immitis antibody, precipitin | Negative | Negative |

| Brucella antibody total by agglutination | <1:20 | <1:20 |

| Bartonella species by PCR | Negative | Negative |

| Bartonella henselae antibody, IgG | <1:64 | <1:64 |

| Tropheryma whipplei by PCR | Negative | Negative |

| Histoplasma antigen, serum | Negative | Negative |

| Histoplasma antigen EIA, urine | Negative | Negative |

| Histoplasma mycelia antibody by CF | <1:8 | <1:8 |

| Histoplasma yeast antibody by CF | <1:8 | <1:8 |

| Histoplasma antibody by ID | Negative | Negative |

| Aspergillus galactomannan antigen | Negative | Negative |

| (1,3)-beta-D-glucan | Negative | Negative |

| Cryptococcal antigen, LFA | Negative | Negative |

| Human immunodeficiency virus-1,2 combination antigen/antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Hepatitis C antibody | Negative | Negative |

| C-reactive protein | 0.4 mg/dL | 0.0–0.8 mg/dL |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 1 mm/hr | 0–10 mm/hr |

| Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, IgG | <1:20 | <1:20 |

| Myeloperoxidase antibody, IgG | 0 AU/mL | 0–19 AU/mL |

| Serine proteinase 3 antibody, IgG | 0 AU/mL | 0–19 AU/mL |

| Rheumatoid factor | <10 IU/mL | 0–14 IU/mL |

| Cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, IgG | 2 units | 0–19 units |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme | 30 U/L | 9–67 U/L |

| Serum IgG4 | 4 mg/dL | 1–123 mg/dL |

| CD19 B cell | 34 cells/μL | 74–510 cells/μL |

| CD4+ T cell | 350 cells/μL | 490–1,600 cells/μL |

| CD8+ T cell | 158 cells/μL | 150–1,050 cells/μL |

| Total protein | 6.70 g/dL | 6.00–8.30 g/dL |

| Albumin | 4.40 g/dL | 3.75–5.01 g/dL |

| Alpha-1 globulin | 0.32 g/dL | 0.19–0.46 g/dL |

| Alpha-2 globulin | 0.84 g/dL | 0.48–1.05 g/dL |

| Beta globulin | 0.73 g/dL | 0.48–1.10 g/dL |

| Gamma globulin | 0.42 g/dL | 0.62–1.51 g/dL |

| M-spike | Not observed | Not observed |

| IgG | 411 mg/dL | 768–1,632 mg/dL |

| IgA | 49 mg/dL | 68–498 mg/dL |

| IgM | 10 mg/dL | 35–263 mg/dL |

The presence of pulmonary nodules on imaging and non-necrotizing granulomas on lung lymph node biopsy in the setting of hypogammaglobulinemia pointed toward GLILD instead.13

Further, the lack of characteristic symptoms, along with negative serologies, did not support other autoimmune causes, such as vasculitis (particularly ANCA-associated vasculitis) or other autoimmune diseases, such as associated rheumatoid nodule, granuloma annulare or necrobiosis lipoidica.14

Malignancy was a concern, with lymphoma, carcinoid tumors and metastatic disease of highest suspicion given the initial aggressive manifestation and presence of necrotizing granulomas. CVID patients are also at increased risk for developing malignancy, at an estimated incidence rate of 15%.1 However, the multiple negative biopsy results and marked response to IVIG excluded malignancy as the underlying process.

CVID remains the most likely diagnosis for our patient. Although IVIG is the mainstay of treatment for CVID, no established guidelines exist for the treatment of associated granulomatous disease. IVIG has not demonstrated consistent efficacy in treating granulomatous disease, though this treatment modality did appear to have a significant impact in treating our patient’s abdominal disease.2

Immunosuppressive therapy has shown positive results in treating granulomatous disease, although more investigation is needed. Chief among immunosuppressive agents are corticosteroids. Additional corticosteroid-sparing agents, including cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab and infliximab, are used to avoid prolonged steroid use or to induce complete remission.15–17